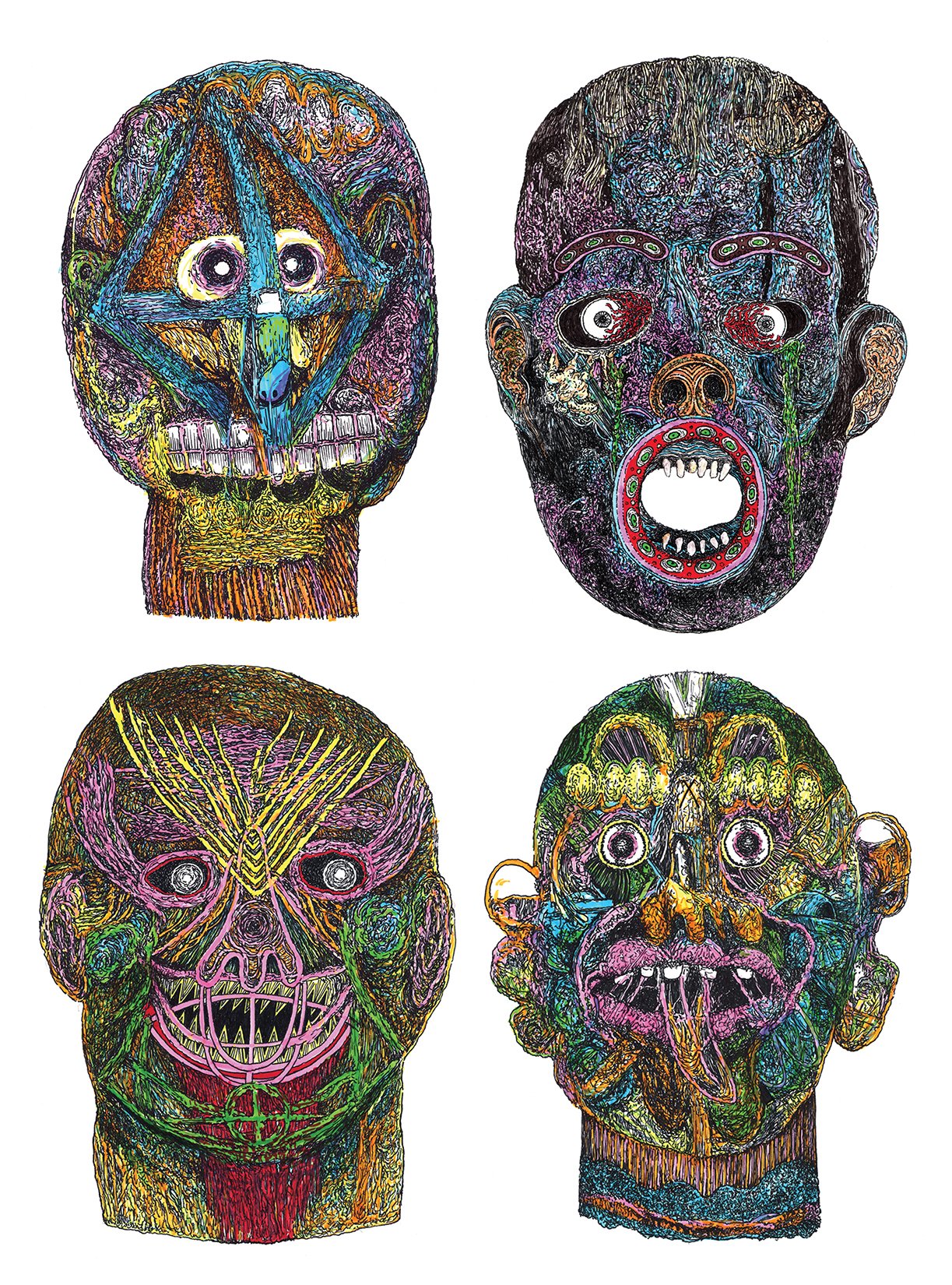

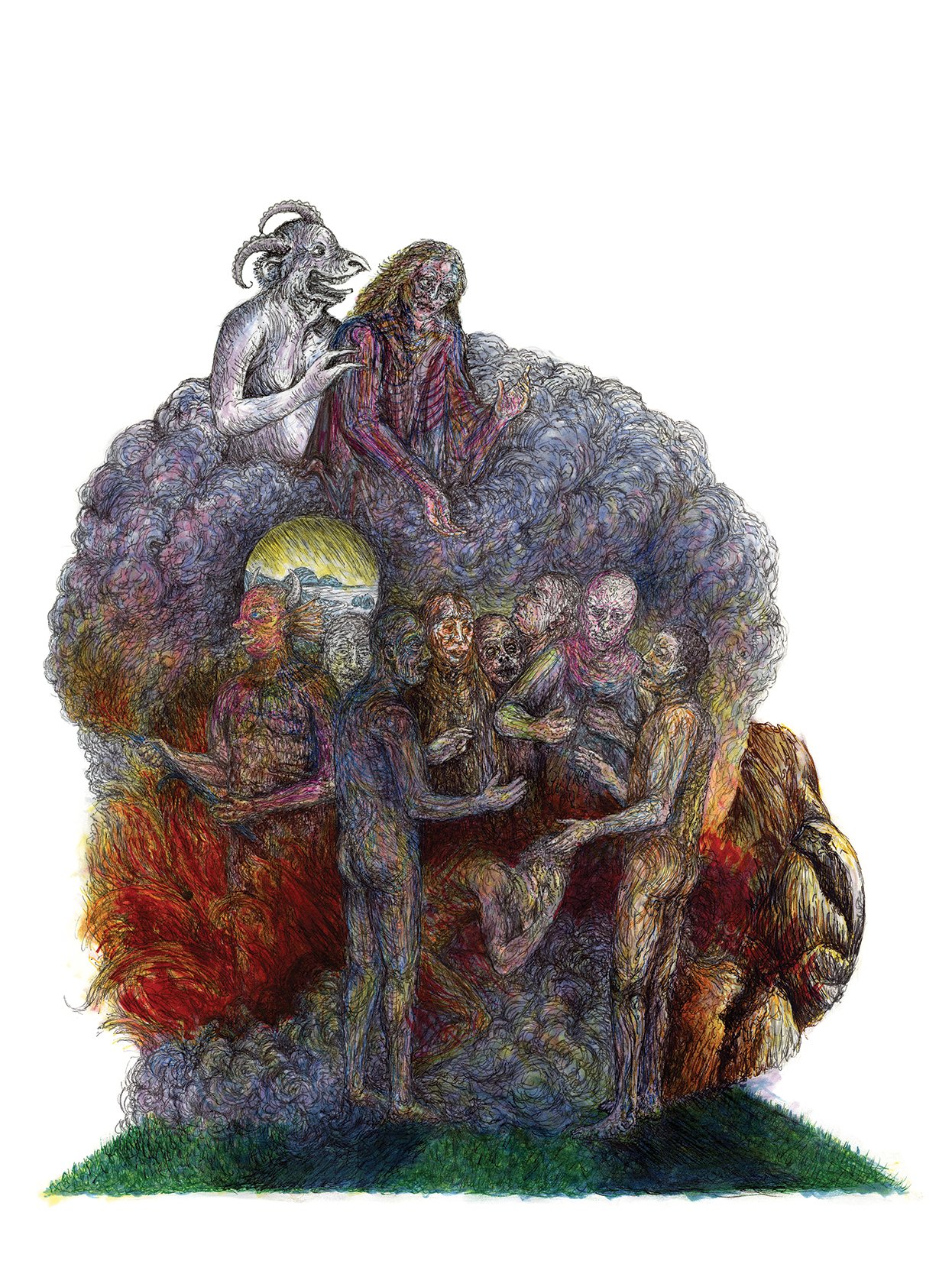

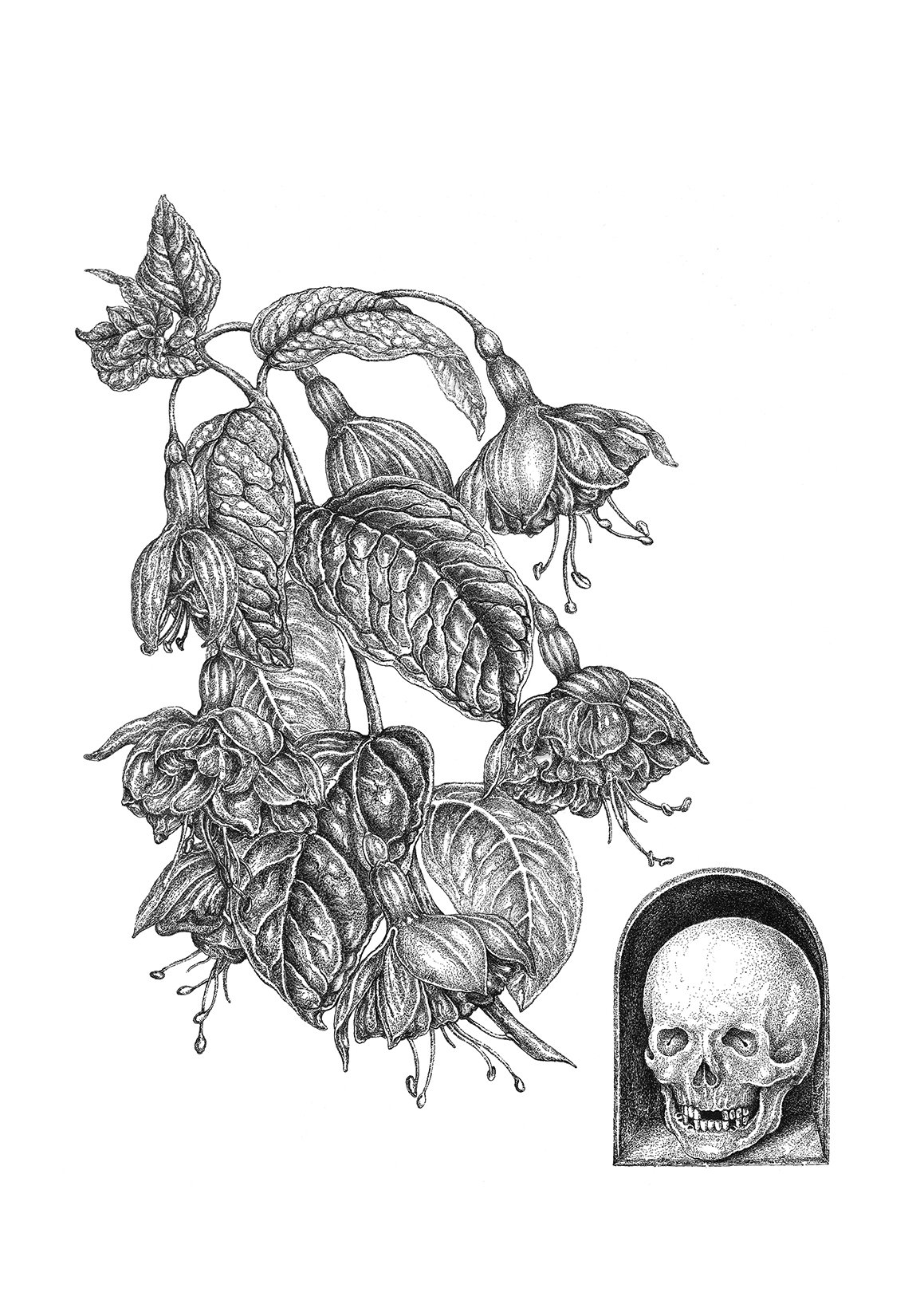

Artist Spotlight: Carlos Estevez

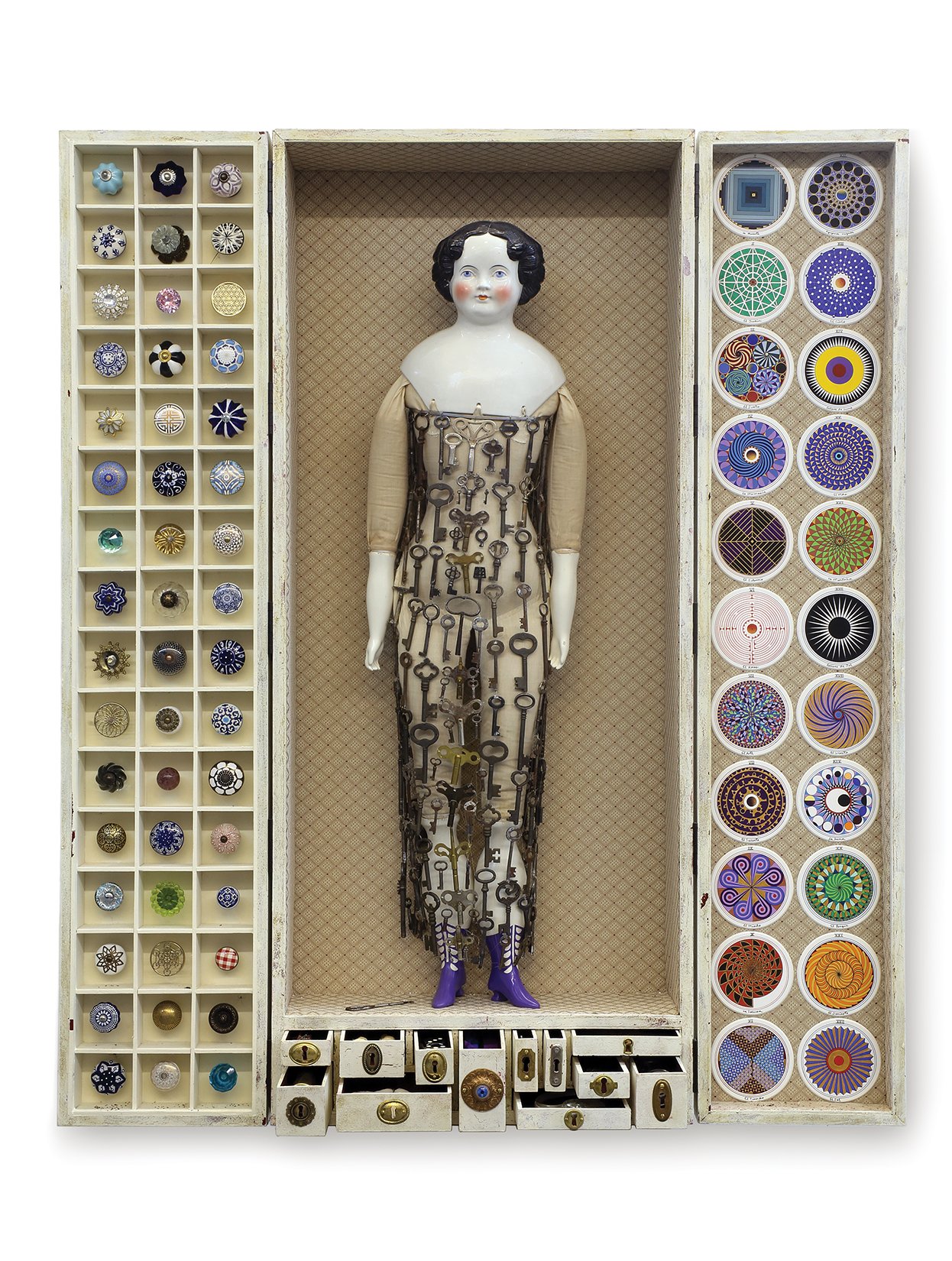

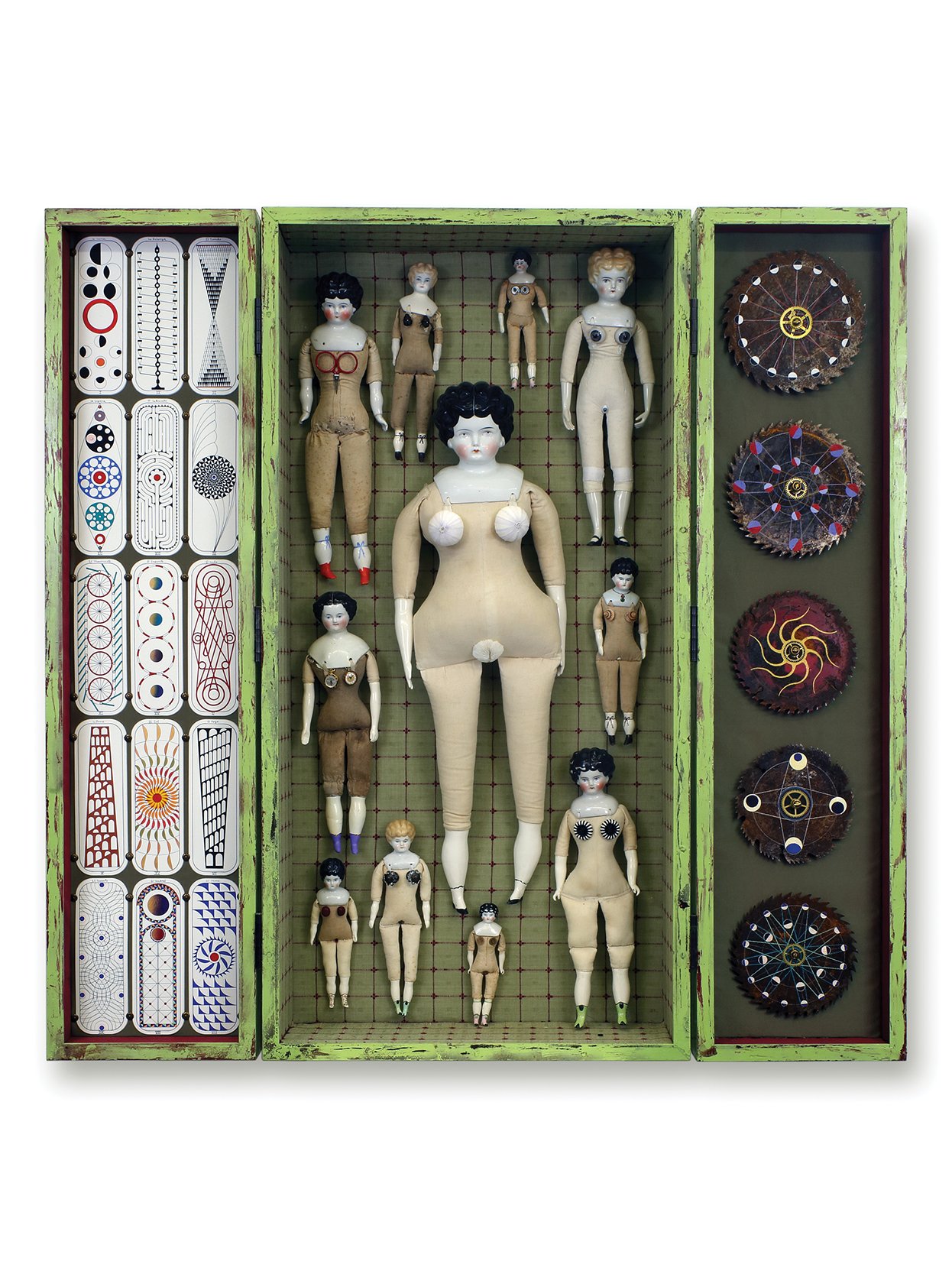

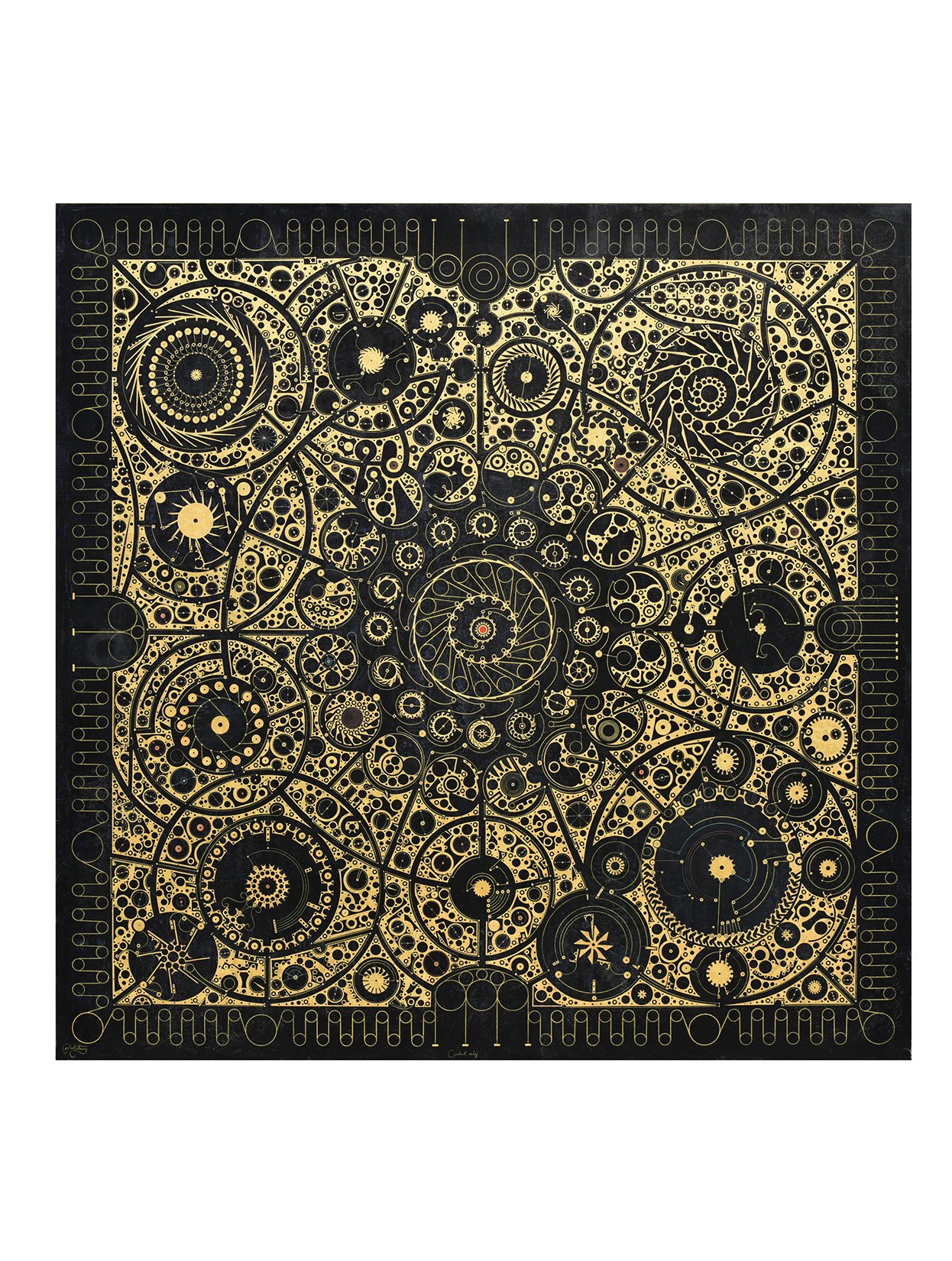

Carlos Estevez’s work is animated by a deep interest in questions of human spirituality. His stated goal is to use his work to reveal the invisible realm to the spirit that lies hidden beneath the visible world, a process that he refers to as an alchemical, metaphysical transformation of mystery into knowledge. The imagery that populates his paintings, drawings, sculptures, and installations bears a dreamy, child-like quality, with recurring references to marionettes, automatons, fantastical architectures, cosmic geometries, angelic beings, and strange, chimerical creatures.

A recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, the Cintas Foundation Fellowship in Visual Arts, and the Grand Prize in the First Salon of Contemporary Cuban Art in Havana, Carlos Estévez was born and raised in Cuba and moved to Miami in 2004, where he lives and works. He graduated from the University of Arts (ISA) in Havana and solo exhibitions of his work have been presented at the National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana; Tucson Museum of Art, Arizona; The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum at Florida International University, Miami; Center of Contemporary Art, New Orleans; Lowe Art Museum at Miami University, Florida; and the Stoors Gallery at University of North Carolina Charlotte. Estévez has participated in group exhibitions presented at the 6th and 7th Havana Biennials; the 1st Biennial of Martinique; Arizona State University Art Museum in Tempe; Pérez Art Museum Miami, Florida; Maison de l’Amerique Latin, Paris, France; Casa de América, Palacio de Linares, Madrid, Spain; and several others.

Estévez has been an artist-in-residence in Academia de San Carlos, UNAM, Mexico; Gasworks Studios, London, England; The UNESCO-ASCHBERG in The Nordic Artists' Center in Dale, Norway; Art-OMI Foundation, New York; The Massachusetts College of Art, Boston; Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris; Montclair University, New Jersey; Siena Art Institute, Italy; Sacatar Foundation, Isla Itaparica, Salvador de Bahía, Brazil; and McColl Center for Art + Innovation in Charlotte, NC; among other places.

His work is included in numerous prestigious collections, such as those of the National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana; Museum of Fine Art, Boston; The Ludwig Forum, Aachen, Germany; The Bronx Museum, New York; Perez Art Museum Miami, Florida; Drammens Museum for Kunst of Kulturhistorie, Norway; Tucson Museum of Art, Arizona; Denver Art Museum, Colorado; Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut; Arizona State University Art Museum, Arizona; Fort Lauderdale Art Museum, Florida; The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum at FIU, Florida; The Mint Museum, North Carolina; BNY Mellon Art Collection, New York; and The Lowe Art Museum, Florida.

Estevez first monograph Carlos Estévez: Entelechy. Works from 1992 to 2018 by Carol Damian, Ph.D. was published in 2019 by Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block, Arizona; also, Images of Thought. Philosophical Interpretations of Carlos Estévez’s Art by Jorge J. E. Gracia was published in 2009 by State University of New York Press, Albany; and Carlos Estévez: Bottles to the Sea, edited by Jorge J. E. Gracia was published in 2015 by State University of New York Press, Albany.

ARTS Southeast was honored to host Estevez in the ON::View Artist Residency in October 2022, and to exhibit his work in the main gallery at Sulfur Studios in ON::View Revue, 2023.

more stories from impact magazine…

more stories from impact magazine…

By the Fire Next Time, (detail.) 2022. Acrylic, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil, India ink, Gouache on Canvas. 60 x 84,” Courtesy of the artist & Kavi Gupta.

When you visit Michi Meko’s website you are greeted with one word,

– INWARD –

this serves as a simple direction leading the viewer to his work but could also be a reference to the work itself. Michi Meko’s paintings are dark, all shades of black are explored: charcoal, shadow, burnt wood – reminders of the darkness of sleep or the unconscious mind. This blackness is punctuated with sudden bursts of color – blues, golds, oranges, reds and whites inform the psychogeography that Meko traverses.

Trelani Michelle tends to move in the other direction – her work as an oral historian leads her outward, into the community, to collect the oral histories of folks in the Gullah Geechee community in Savannah, Georgia and beyond.

Trelani and Michi made time to plumb the depths of Meko’s work and share their thoughts on the experience of spiritual retreat in the wilderness, the gifts of Mami Wata, the joys of fly-fishing, painting, and why Michi Meko is the King of Collards.

Trelani Michelle: When speaking about your work you’ve said “The use of navigation is one of the skills required for any journey” and that oral history is also a framework. While oral history was practiced by all people, I feel like it's inherently ours. I read something about the characteristics of white supremacy and the worship of the written word, which automatically devalues, within the white worldview, the spoken word and the feeling and intuition of the thing. That’s something that I feel within your artwork: a lot of intuition and feeling. Because that written word can kind of be unyielding, right? But oral history allows for more flexibility, more changing with the times, and maybe even more buoyancy.

I was looking at your Artist Statement, and the first line took my breath away: “In the summer of 2015, I almost drowned.” That is brilliant storytelling, it hooked me right away. The ocean holds so much trauma for our ancestors, yet it also offers so much healing to our bodies.

Also in your Artist Statement you say: “We’re navigating public spaces… we’re consistently threatened while remaining buoyant within them.” So that buoyancy and navigation – those are central figures in your work.

Michi Meko: In 2015, I almost drowned in a river, so from that experience I began to invite that event into my artwork and accept what that was. And in a way, it became – I guess a near-death experience becomes like a reset. And after the event, I began to look around and think about what it meant to be buoyant. And so I went on a journey to try and figure out, historically, why Black people fear water, why Black people can't swim, or why Black children drown more than white kids. Why I'm a very proficient swimmer, but still almost drowned in a kayak, you know what I mean? So it just sparked all this kind of stuff.

And then I had a friend who is an anthropologist tell me about Mami Wata and that belief system. And things were then starting to happen to me. Like, yes, I became very calm. Yes, she took the best of what I had. Yes, I did begin to make money. And yes, ladies began to say I was handsome and all this other stuff, right. Then all these things began to happen, and one night in a dream, she appeared and invited me back. And it was just like, I have things to do. And she was like, Are you sure? And I was like, Yeah. And then boom, didn't see her for a while. So I just began to think that was strange or was a part of my subconscious working; or, there's something really to this, you know what I mean?

A Beautiful Free Uneasy: The Rhododendron Cave hide out, 2022. Acrylic, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil, India ink, Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Monofilament, Gouache on Canvas. 66 x 84 in. Image courtesy of the artist & Kavi Gupta.

And, because I am a fisherman and outdoorsman, I would then go – I still do – take gifts to the water. And the one time that I didn’t – I used to wear this beautiful necklace that had a chain and float on it, that someone made me to keep my head above water. And it seemed like that chain just broke off for no reason and fell into the ocean. Then when I pulled out my crab basket, I had more crabs than I've ever had. The quickest I've ever gathered crabs. So I thought that was kind of strange or funny. And so I just began to invite that situation and those thoughts into my work. I began thinking about my father and his inability to swim. I was thinking about Jim Crow and what that did for a generation of swimmers - the fear that caused and the fear that continues to cause. Then I began reading historical records about the Africans being very proficient swimmers.

So it was something that was very strange to me, that there’s this thing that we've lost. So I just began to make work about that, and to be very considerate of what it is that I was doing and how it related to Black people.

So far as white supremacy and all that, that's white people's problems and my work don’t have nothing to do with white people. I do not center them at all. It is only about me. Things that I think about, things about my family, philosophical thoughts that are mine, and the things that I develop or research and try to create a pedagogy for. But so far as white supremacy like that, that's on white people, that ain’t on me.

TM: Yes, oh yes. So it's like… it exists. It's out there. But when I go home, I close my door, I get in my car, when I’m walking down the street with my earpods in – that ain’t got nothing to do with me.

MM: That's not my problem.

TM: Right. And it's evident in your work like, it’s all things blackety black. I knew you were Southern – I saw that you were Atlanta-based – I had to do a little more digging to see the Florence, Alabama. But when I saw that cast iron skillet, that Cash Money-looking album cover, the work songs – spirituals, really – and the collards, I was like, no, he is like, Southern, Southern, Southern. He's like that Great Migration – we didn't leave, we stayed – kind of Southern.

MM: Yeah.

TM: Did you grow up in Florence, too?

MM: Yeah, I grew up in Florence. And a lot of my work is about that statement you just said, right? It’s about recognizing the cultural retentions and how they stayed and how we continue to thrive or use those in our everyday lives. And yeah, we may not be Africans. Yeah, we are Americans, but we still have those cultural retentions that definitely tie us to that land. And my thing is – I am very proud of who I am as a Southern man. I'm very proud of our contributions to American history and to culture. And I think it's up to me with that work or some of my work to tell these greater narratives - beyond Black trauma.

TM: You named your mother as an artist. Did you always see her that way, or just in retrospect?

MM: Um, no. She was the one who kept me flush with paper. She was the crafty, creative one. My dad was the scientific one. And I kind of credit her with that, with sort of fostering that – what do you call it? I don't know – the creative whims. But then as I've gotten older, the later work has become more science-based – they’re more about my father. And so the skillets and all of that was more about my mom. Because she gave me a set of skillets, and she told me that “these skillets will outlive you if you take care of them.”

Michi Meko in his studio. Photo by Chad Brown.

Which threw me down the path of thinking about how these are our heirlooms. We may not have material wealth to give to our kids or to hand down, but the pride in taking grandmother’s skillet – there's something to that. So I begin to think about these objects as symbols of wealth, and they begin to then take on a life of their own within my imagination. Thinking about how I'm going to die at some point, my mom's going to die at some point, but this skillet will still be on earth, you know? And that's strictly from her statement. So I began to want to make skillets that went into permanent collections or went into the histories of this narrative that I'm telling – and have someone handle them with care. It is simply a selfish move.

So that sent me on a journey chasing how far I could trace back a collard green recipe in my family. And then, as my family is all competitive, to see who can make the best greens. That's why I say I'm the king of collards, because I make the best ones.

So, that's a bragging rights thing. Like, who can grow the best garden, who is the best fisherman? One of my cousins, older cousin, passed away and his son stood up in the funeral to eulogize his father and he goes, “At least I'm the best fisherman in the family now.” And all the boys in the family in the middle of this funeral were just like, “Hey, wait, what?”

There was a real eruption about what that meant. So that's something I take a lot of pride in. I don't have to continue to celebrate great trauma. I can look at who we are as a people and what we've contributed beyond just physical labor. But then, within that labor, there are good things that have come out of that.

TM: Word. What did you want to be or do when you grew up?

MM: At first I wanted to be a drag racer.

TM: Interesting!

MM: Yeah [laughter]. Because I had an uncle who raced cars and built cars, so I wanted to do that too. And then at some point I got into skateboarding, so I was going to try and go pro at skateboarding. And that was a time when there weren't a lot of Black skateboarders.

Crappie Painting: Render An Apocalypse. A Life for a Life. How To Kill a Fish., 2022. Acrylic, Acrylic 60 Gloss, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil, India ink, Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Monofilament, Gouache, Fish Scales, Fish Glyco Protein, Yellow GA Corn Grits, Pur Glass Preserve Jars, Wooden Crates on Canvas, 91 x 66 in. Courtesy of the artist & Kavi Gupta.

TM: Yeah - still! So then that ties into your graffiti. I see the skateboard-graffiti connection a little bit. Is that around the time you started doing that?

MM: Yeah, but graffiti comes out of hip hop. My lens for my work is graffiti and street based, but it's also Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley, all the great artists – Jack Whitten – who came out of Alabama. But then, like, what? What does that sort of tradition translate into when you give a kid MTV? You know what I mean? And so my foundation, or the way I think about stuff and the way I talk to my other friends in the art world about what it is we make and what it is we do – we describe it in terms of funk and hip hop.

But the art was always there, and I knew that would be the thing that I would do. At some point I got into rap groups, and we had a production deal with Jimmy Henchman. That didn't work out – and I'm thankful for that. But it was always there, the art was just always there.

TM: Yeah. My son who is 17, when he saw your work, he was like, “I don't know, something about it reminds me of Big K.R.I.T.” And I was like, “that's interesting you say that, because he's from Mississippi.” Isn’t he from somewhere around there, Big K.R.I.T.?

MM: He’s from Mississippi.

TM: But I was like, “I can see it, CJ!”

MM: Yeah, he hit it, even though he went off his gut, right? That's what that's about. These kinds of communications that we understand – it's coded, it's heavy, it's laced, but then it's so universal that it just becomes Southern because a lot of our experiences are a lot of everyone's experiences, from the poor white to the poor Black.

There's a lot of comedy in my work. There's a lot of jokes. The titles have things that I want people to see within the work, things that I want to see on a notecard or on the gallery card, things that I want to exist in history, language I want to get into history.

For a while, I named a lot of my paintings after rap songs. Lately I've been having fun putting curse words in the titles. There's a show I finished last summer – one of my favorite ones was called Cucka Bugs.

TM: That’s Southern.

MM: Yeah, which is actually the little burr that you get on your pants, but then also the gnats in the back of your head. So there’s a lot of jokes – but then these coded messages. So it’ll be like, ha ha, here's some super Black shit, but here's some funny shit, and then if you can decode it, you can get the joke, kind of. But then it's a very serious thing that I'm trying to say, at the same time. I'm just a dude who overthinks it.

TM: Perfect. That approach reminds me of the Atlanta series, because it was so serious, so teachable, but so hilarious. When do you know you're done? I saw a meme that said, “When we season our food, the ancestors will whisper, ‘That’s enough, child.’” Is that when you know you're finished with a particular piece, or a series? Or how do you know when it's done?

MM: Yeah, it's kind of like that. But I don't know if mine might say, “that’s enough, child.” It’s more like, “yeah, I’m finna do it now. Like, that’s it, you’re on - oh shit, wait til they see that.”

Yeah, I feel like the painting starts dancing. It starts being like, “yeah, that’s what I needed.” Or it’ll say, “I need one more thing.” You know what I mean? So, again, in terms of hip hop, it'll just be like, yeah, you’re gonna kill it with this one. Yeah, I’m on now. And then I'll send it to my homie – and he's from Jackson, Mississippi, and he makes art at a high level - Felandus Thames. And if I can get the seal of approval from Felandus, because he knows the language that I'm speaking through material, the subject matter – he’ll be like, “yeah, that's it, cuz.” Boom. Like, we'll throw all the high art talk out and just barbershop talk, you know what I mean? About art.

TM: Yes. Bilingual.

Portrait of Michi Meko. Courtesy of the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC.

So one of my favorite Zora Neale Hurston quotes – because she's an anthropologist too, she says she hates routine. She said, “Don't be surprised if I take to the woods.” Which, you do that! When you go out to the woods – what’s happening while you’re out there? What are you doing, what do you think about?

MM: I always say you’ve got to face the demons. And as a kid, you know, you grew up in the church, and old people would testify and say the devil tried to make them do all this stuff. One I remember fondly and laugh about was a lady testifying about getting a flat tire, and she said the devil got into her tire and, you know, made it flat.

But then you go outside and look at her car – the tire is bald! And it’s like, it wasn't the devil, it was you. You need to buy new tires. She tried to put that on the devil. And that's when I began to realize that we were the devil.

And so that’s what shifted my thought: in church, people would testify, “The devil tried to do things.” And I would just look at them and be like, “Huh, you're the devil.”

As I got older, I began to think about it like, “I have to go out and face my own demons, and be real or be true to myself.” But for the most part, I was trying to find a way to deal with my bullshit. And I think that's something we don't do often. And then, when you think about it from a Black male’s perspective, there's never much conversation about Black males sort of dealing with their bullshit, and how we deal with our bullshit. So running off to the woods and doing all these things sort of helped me deal with my bullshit.

TM: That's a powerful practice. That actually reminds me a little bit of something too. I’m reading a book, ‘Rest is Resistance’, and [Tricia Hersey] talks about how a grieving person is a healed person, but our country doesn’t want – capitalism doesn’t want – healed people in it. Because if you aren’t healing and you aren’t grieving and you’re just pushing through, you’re just grinding through – you’re just working, working, working, smothering it down. But now you go out to the wilderness and let it all come up. That reminded me of something you said in a Hulu Artist-in-Residence clip: you make work that’s poetic, but then there's a darker side that you enjoy most.

In another interview, you mentioned that the darkness is a space we can’t avoid - you have to go there. And that you had to go visit the beach once to release the remnants of that dark space that you entered. So it's like, it is hard. That dark place is necessary. I totally agree. And I also agree that it's difficult. But you said you enjoy it the most. Why do you enjoy it?

MM: Because you get to face it. I don’t know, maybe I'm sadistic, but you get to lighten the load. Like, there's a lot of room – that’s a good question, shit. I’m usually not stumped, but like – why do I enjoy the dark part? I don't know, yeah, I feel like I'm lightening my load. It’s a good place to sit and just face it. And that sort of honesty with oneself, there's something very freeing, something very liberating in all of that.

TM: It is. Actually, I think you hit it on the head without needing whatever the word was, the right word you were trying to find. I deal with my own grief and darkness, but when I acknowledge I'm there, I want to get on up out of there. Let’s open up these blinds. Let's turn on some music, because we’ve got to get up out of here, we can’t stay in this feeling. But, like you said, – now I'm walking around with a lot inside – it’s like I look forward to the breakthrough moment. Like when we talked about the church, right? Those breakthrough moments, when you just break and then you flood and you’re like, ok, it’s all out. So you just go into the woods and just lighten the load. You get all of that day-to-day, moment-to-moment, goal-oriented, success, failure – you just get all that shit off.

MM: None of that’s important really, right?

TM: Yeah. Speaking of what’s not important: you ain't on social media like that. You know, artists are booming – social media's one of the greatest tools ever for artists. You don't feel like you're missing out?

MM: I make good work.

The Ants Can Have My Body: Too Far out to turn back, 2022. Acrylic, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil, India ink, Gouache on Canvas. 82.5 x 66 in. Courtesy of the artist & Kavi Gupta.

TM: I dig that. That’s timeless. Social media ain’t always been here.

MM: The reason for that though, for real, is that I began to have some anxieties about it, I began to recognize mentally that something was not right. I've never felt these feelings, why am I feeling this way? Why am I comparing myself to people? And I heard a quote from Jack Whitten, “we do not know the long-term effects of social media.”

That resonated with me. And I just began to think: what photo can I even put up that would mean anything to anyone? One of my favorite photos is Yves Klein, where he takes the leap. I thought, if I can't produce a photo that's just as intriguing or as beautiful or as poetic as that, then what am I posting? It's just bullshit, right?

I then began to think about mythology, and was there a way to be visible while being invisible? Could one go against the algorithm by participating in it slowly, curating whatever these experiences are that we're having on social media or this thing that we’ve become addicted to? And I was like, okay, at this point I am going to repel ghosts and I'm going to disappear.

So I set about creating another Earth. I am in an experiment of trying to be visible but invisible. Trying to be invisible within my invisibility online. And so I only post stories, and those disappear. So there's something very ephemeral about that, that I like.

But then, within all of that I just knew it was fucking with me. It was messing with my brain. And then after being off for a while, I was like okay, I'm starting to feel better. Like, these things are more important, whatever. And then start to realize that people kind of miss you, but not really.

And so I disappeared. And I sort of just added to the mythology of being visible, but being invisible at the same time.

TM: Yeah. And that's – if you ain't got that curiosity, willing to explore and and see what happens, you know, you ain’t no real artist. And not just on the canvas, or just in your work, but in your life. You’ve got be forever curious, and willing to just see.

MM: Yeah, I just disappeared and recovered. So it was that sort of thing that I've sort of wanted to create for myself to add to the idea of a mythology that I'm sort of working on in my head. It’s a giant conceptual thing.

TM: It is. Do you consider yourself successful?

MM: I've had a studio for 20 years. That has always been my measure of success, whether I could keep a studio.

TM: I love it, I love it. So if you cease to have your studio, you wouldn't consider yourself successful anymore?

A Fugitive GPS, 2022. Acrylic, aerosol, oil pastel, gold leaf, aerosol hologram glitter, white colored pencil, india ink, gouache on canvas. 72 x 48 in. Courtesy of the artist & Kavi Gupta.

MM: Yeah, because that means I didn't do what it took to maintain that. The thing that I say, “I love this, I’m going to do this for the rest of my life” – if I can't maintain a space to do that, then I just lied to myself.

TM: I dig that. You've got to be a little buoyant and take your studio in the house if that happens, though.

MM: Yeah, so like I said – always maintain the studio.

TM: Always – yeah, no matter what that studio is, always maintain the studio. You mentioned analog Afrofuturism too. Can you elaborate more on that concept?

MM: Everybody wants to go to space; they just want to run to space. Everybody just wants to disappear. Everybody wants to go to the future, but nobody wants to build a spaceship. And by the way, somebody's got to stay on Earth and build a spaceship, or somebody's got to start the plans, or somebody's got to begin to think about right now. Because if you don't solve the problems now, you only take them into the future.

So the idea of Afrofuturism is just bullshit if you don't try to solve it now. We've always been futuristic. And I don’t need someone else’s language to describe my futurism.

TM: That’s that Southern in you too, that’s that whole, “I’m not migrating up north. I’m staying where I’m at.” That’s that church saying, “Noah had to stay to build that ark.” So yeah, it's a convergence of all those things. It’s a family reunion in thought. I like that.

MM: Do the work.

TM: Do the work, right – daydreaming is important too. Migration is integral, I get that too – but there’s still some work involved. Then you can retreat to the wilderness, but you have to work.

MM: Everybody’s painting and styling themselves as futuristic negroes, but then it’s like, for what? Y’all ain’t even got no blueprints. How are we going to get them? Have you sent a team out to see what even grows there? If you look at some of my work, it's got seeds on it. It’s got dry seeds like okra. That would be the one thing that I would take.

Like it’s the one thing we took. So you can be philosophical about it all you want. But we can’t walk inside a building that W.E.B. Du Bois built. We can walk inside in one that Booker T. built.

TM: Yes. Now you took it back to the Du Bois and Booker T. argument.

MM: You know you really have to pause and think about how you want it. But yeah, it’s one thing that I’ve thought about. You can't walk inside of a philosophy.

TM: Tell me about your book, Black Navigation.

Cucka Bugs: Cold was the Ground. Barren Trails, 2022. Acrylic, Aerosol, Oil Pastel, Gold Leaf, Aerosol Hologram Glitter, White Colored Pencil, India ink, Sequins, Tassel, 4lb Mr Crappie Hi Viz Monofilament, Gouache, Wood Satin on Panel. 75 x 73 in. Courtesy of the artist & Kavi Gupta.

MM: It's an idea I've had since 2017. I wanted to create a book of field notes. I wanted to understand what my voice sounded like in the wilderness. What does a Black male voice sound like in wild spaces? Can I have a transformative moment, and what would that sound like? Because most of what we know – or the romantic parts that we know, a lot of the great quotes – they come from white males. So I set out to try and find my transformative moment and make my great quote. I don't know that I've done that yet.

I wanted a record of Black existence in wild spaces. Specifically a Black male’s voice. I was just curious about what my voice would sound like.

TM: Yeah, I love it. Did you figure it out, or is it a continual exploration?

MM: I'm still writing. I have a whole lot of notes for books, so I'm gonna try and do another book. I might do an album with it and all that kind of stuff. But when someone reads, “cold mountain streams on my Black nuts,” that's truly an experience Black men can have. Only a Black man knows what it's like to have cold nuts. So it’s got this kind of humor.

TM: Yeah. That's For Us, By Us humor. Where is your navigation pointing you these days?

MM: I'm still in the wild, still in the woods - a lot more fly fishing. I just did a documentary about my process, explorations and fly tying with a guy named Chad Brown from Love Is King - he’s the man when it comes to the outdoors and Black explorers.

So, yeah, I'm going to keep trying to be my best Matthew Henson. Keep trying to tell good stories. Keep trying to make it super Black, but super universal. And just tell these beautiful narratives from my perspective.

###

more stories from impact magazine…

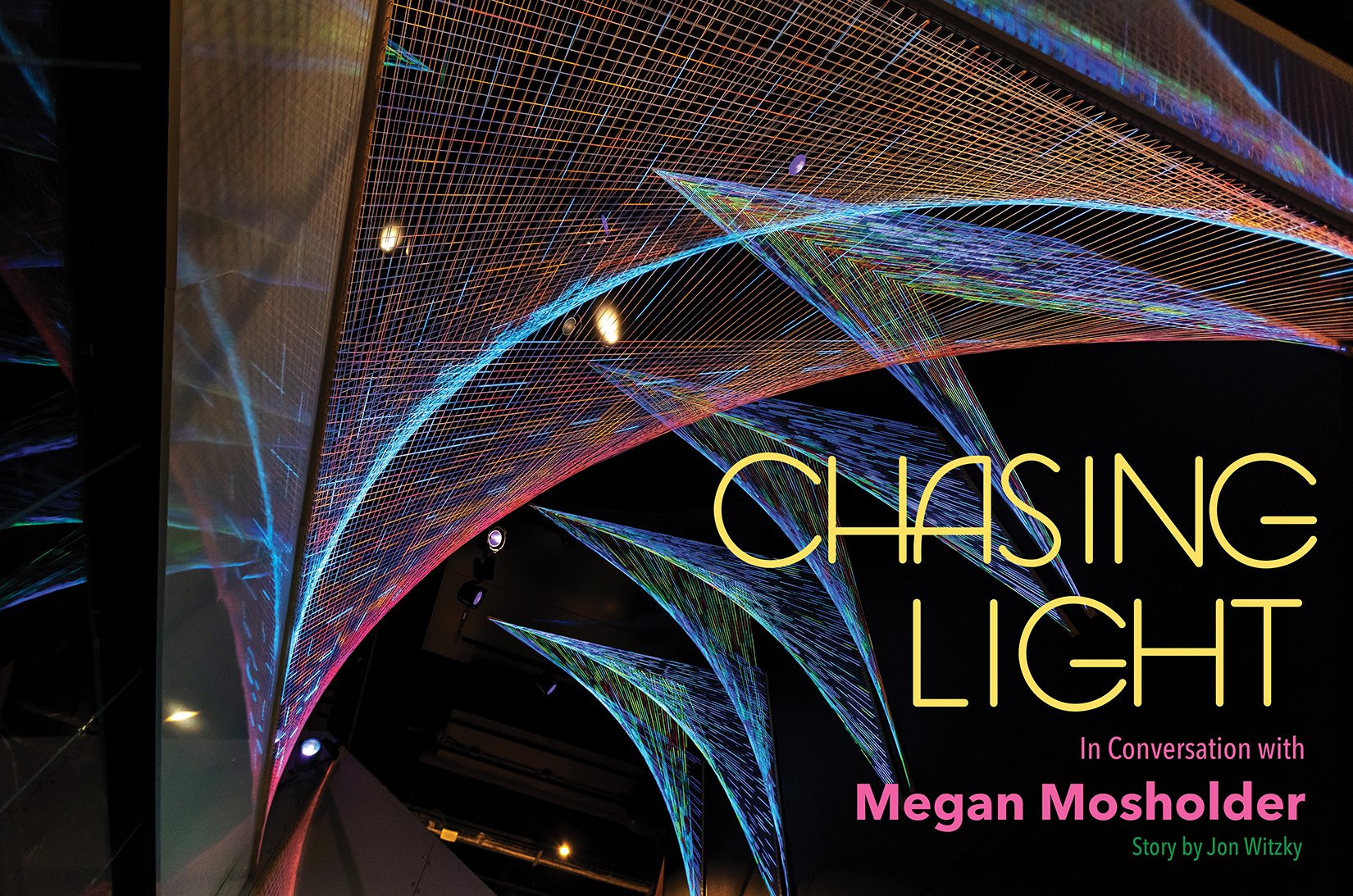

Google, Luí na Gréine (Window of a Sunset), 2021. Hand-painted string illuminated with black light, 636” x 81” x 96”. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Megan Mosholder works with the basic elements of design - line, shape and color - but the true star of the show is light.

Mosholder’s parabolic, site-specific, sculptural installations augment and reinvent the spaces that they occupy. Through the use of paracord and UV sensitive paints, these web-like structures come alive as the sun goes down.

Beginning her career as a high school teacher, Mosholder decided to change focus to concentrate on becoming a full-time artist. In our conversation, Mosholder recounts her time as a student, a teacher, an artist assistant and a working artist who has earned high level commissions by corporations like Microsoft and Google. In 2018, a tragic car accident burned over 60% of her body, forcing her to endure a medically induced coma, over 30 surgeries and an amputation. Mosholder had to learn how to navigate the world in a new way - but with the same grit, determination, and wonder that she has always approached her work, eventually landing a coveted exhibition at the 59th Venice Biennale.

Megan Mosholder, with Terminus II in progress. Terminus II, 2020. Steel and rope, 247 x 192 x 247”. Permanently installed on Atlanta’s Westside Trail. Atlanta Beltline Portraits, photo by The Sintoses, 2020.

Jon Witzky: I'm going through your work and it's amazing, the trajectory that you've been on. I feel like your ideas were fully formed from the very beginning – I’m thinking of pieces like the wrapped rocks at SCAD’s Lacoste campus [400 Wrapped Rocks – Provence Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France, 2011].

Megan Mosholder: Yeah, that was my first major installation.

JW: It's really beautiful and simple – quite lovely.

MM: Yeah, that came out of meeting Teresita Fernández [visual artist and sculptor known for large scale public works]. She was at Lacoste when I was there, and she pushed me out of my comfort zone. I was still trying to make some form of paintings and she said, “You're not a painter, you’re a sculptor, and you're working way too small.” And I was making these four by eight foot paintings. And I was like, “That's small?” She was like, “Way too small.”

JW: Did you end up working as her assistant in Brooklyn?

MM: I did. SCAD allowed me to transfer into the remote eLearning program, essentially, so I could finish my degree while working with her in Brooklyn. And it was phenomenal.

JW: What were you doing for her?

MM: She was working out of her garage and she had me smashing rocks on the concrete floor with a hammer that we were then bleaching to make this fool's gold look like actual gold. It was for the piece that she installed at the Louis Vuitton in Shanghai. [Teresita Fernández: Yellow Mountains – Louis Vuitton Shanghai, Shanghai, China, November 30, 2011.]

It's like ten thousand rocks with ten thousand little hooks attached to the rocks hanging from ten thousand gold chains.

JW: That was your education.

MM: That was my education. She also had me doing things like taping straws together and she would send me to the art supply store to get colored pencils. And she'd say, “Don’t tell them who it’s for.” I wouldn't say she's secretive, but I guess she’s cautious about who knows what she's doing.

JW: Sure, all artists have their secrets – there's got to be some mystery left in our work! How long did you work with her?

MM: I ended up working with her for eight months. And then I ended up working with a performance artist, Nadja Verena Marcin. I traveled with her to a residency in upstate New York to help her dye this iconic waterfall that was actually in a Turner painting while her boyfriend helped set up the large format camera and she dressed up like a Native American to reenact that painting by Turner.

When she interviewed me she asked, “You're still in graduate school?” And I was like, “Yeah.” And she's like, “Why are you so old?” As only a German would do, because the Germans are just so blunt. And I was like, “Because it just took me a while to get to my MFA I guess. I took the long, roundabout way to do that work.”

JW: I think that's the best way, though – I often feel for really young people who are getting their MFA – it’s hard to make work when you haven't even had a chance to have a life yet.

MM: Well, and you're also going to be really heavily influenced by everything around you. When I started my master’s program at SCAD, I had already been a high school teacher previously, so I was relating to my professors as colleagues – and I don't think they really liked that because I was supposed to be a starry-eyed grad student. I think I was jaded by the time I got to SCAD.

Because the whole point of grad school is to create a body of work to be able to use for applications. And then, of course, you’ve got to maintain that momentum if you want to keep getting opportunities. On my first day on the job with Teresita, she goes, “Wait, you moved here? Do you know how many thousands of people are out there trying to do what you're trying to do?” She was like, “You need to live in a place that's really inexpensive so you can put everything towards your work, especially straight out of grad school.”

And she was right. There's no way – you know, I'd probably still be a bartender, or maybe I'd be teaching high school again if I had stayed in Brooklyn.

I mean, I love New York City. I think that New York is the first place I felt truly normal because there's so many creatives. Everybody's an artist or a musician or an actor. But it's just a really hard place to survive.

Trail By Fire, 2019. Wood, charred wood, ash, eyelets, and hand-painted string illuminated with black light, 96 x 108 x 108”. Photo by David Batterman

“Trial by Fire was an interactive, site-specific, self-portrait depicting both the horror and the beauty of the severe car accident I survived five years ago. I’ve visually built my “new-normal” and strength as a burn survivor into this sculpture with charred wood and ash. This installation is evidence of the impact of my experience and shows how that experience has influenced me as an artist. A new door has opened, and I have crossed the threshold.” – Megan Mosholder

JW: I saw somewhere you had referenced ‘The Poetics of Space,’ which is a wonderful book by Bachelard. What is your thought about the meaning of the landscape? The meaning of space?

MM: You know, I feel like ‘The Poetics of Space’ is a graduate school mainstay, right? But I was just really taken with it.

I've always said it was about the space between the strings, not the strings themselves. I want my audience to see and acknowledge their surroundings. I often build things above people's heads – I want people to look up. People spend a lot of time looking down – especially now that we have these phones – and they don't see their surroundings.

As artists, we’re trained to see things the way regular people are not. So we notice minute idiosyncrasies and changes in color or detail. And I guess I'm trying to do that for the average person, get them to slow down and look at what they're seeing and pay attention.

I've always said that I don't make work about myself. You know, I just build it. It's not about me, and I never wanted it to be about me – it’s about the people experiencing it.

JW: It's really generous for an artist to say “Here, I'm making this for you to have your own experience with – to have your own understanding.”

You’ve said that historically, your work hasn’t been about you – but then you really confronted your own experience in ‘Trial by Fire,’ which you have referred to as a self-portrait.

MM: So I came out of this catastrophic accident, and everybody kept saying, “Oh, I can't wait to see how this influences your work.” Which really irritated me – almost pissed me off because I was like, “I don't make work about myself – why would I start now? I'm still the same person.” Then I had an opportunity at Mint in Atlanta, and I was like – what the fuck – let's just build a self-portrait, rip that Band-Aid off and get it over with so people will stop bugging me about it.

Leteralle (Self-Portrait), 2022. Projections, wood, fabric, string and blacklight, 120 x 72 x 120”. Installed for the European Cultural Centre’s group exhibition, Personal Structures: Reflections, which was on view through November 27th, 2022 in Venice, Italy during the 59th Biennale. Photo by Auston Robinson.

I think that's an interesting piece to mention, especially in regard to what I am working on right now. In that one, I included all these charred elements – I was pointing to the beauty in the decrepit. I was trying to articulate for myself what my current situation was – how it influenced me. One of the reasons why we become artists is because we have things inside us that cannot be expressed with words. We have to make it visual because we're visual people.

And sometimes you have things inside yourself that need to come out so you can heal and move forward. So that was the beginning of me trying to articulate what had happened to me.

JW: You talk about the idea of art as a mechanism for healing. In an interview that I read, you were talking about people in Ukraine protecting their landmarks and how that kind of opened your eyes to the importance of art. [ARTS ATL: “Artist Megan Mosholder soars above tragedy to exhibit at Venice Biennale.” Gail O’Neill, April 28, 2022].

MM: Yeah, I think at that time I was grappling with the idea of what I was investing my time in and I was thinking: Is this the best use of my time when there are so many people out there hurting and struggling? Then I saw that the Ukrainians were wrapping their cultural objects in foam to protect them from the bombing. We’ve seen over the years in wars that the people often take measures to protect art objects. That was a reaffirmation to me that I was doing the right thing, that what I was making and what I am doing is important and can potentially be important to more than just me.

JW: Yes, absolutely. Going back to what you were saying earlier, that you never made work about yourself; the reality is, it's always about yourself to a degree.

MM: Yeah, you're right.

JW: But to embrace that and recognize the universality of the experience is important. The piece that you made for the Venice Biennale, ‘Leteralle’…

MM: That was something that I originally built in New York, in Brooklyn, and then rebuilt in Venice. It was an excellent piece. Being there for the opening was pretty powerful, I really love watching people interact with the work. I actually got a video of this little boy who was dancing around in the room – he paused to look at it, and I said, “You can go inside of it.”

And he turned to look at his parents to make sure it was okay. And I was like, “Yeah, go ahead.” And so he went up and he danced inside of it. And, you know, I love it when that type of thing happens, you know, that's the impact I'm looking for. I want to take people outside of themselves for a moment.

JW: That’s a beautiful image in my mind, of the child dancing in there.

MM: Yeah. Well, I had some adults dancing in there, too, which was kind of hilarious because they're dancing on top of this horrific sequence – but kind of funny, right? Because, you know, I guess that's how I choose to look at it. I try to look at my perpetual recovery with a sense of lightheartedness, because otherwise it's just too heavy and it’ll pull you down.

JW: I think the fact that you had that work to do and that you had the mindset to be able to enter into that, is really incredible.

MM: It definitely helped me heal. I don't do well when I don’t work.

In Venice, I was struggling with pain and exhaustion and spending more time in bed. And I thought, you know, this is a really expensive trip to be in bed all the time. Like, I can't even go out. Even though Lucas [Mosholder’s studio assistant], like I mentioned earlier, would bring cappuccinos and cannoli and stuff to me in bed, which was amazing.

Leteralle (Self-Portrait) detail. Projections, wood, fabric, string and blacklight, 120 x 72 x 120”. Photo by Sam Light.

“This installation was originally built at the Carrie Able Gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn for the Boundless Sphere group exhibition in 2021. It is a self-portrait that further delves into the aftermath of my catastrophic car accident, my eternal state of recovery and my fierce refusal to accept my immobile state of being.”

– Megan Mosholder

When I came home, I kind of crashed and I had the realization that I am disabled. This is not going to go away. This is how my life is now. And although I believe that I will eventually get rid of this wheelchair, it's just taking so much longer than I had hoped. That was a really hard realization to come to, and I plummeted. I nose-dived. At the same time I was living in this apartment in Smyrna while my studio was in Grant Park, and I'm not currently driving and couldn't really afford to keep taking cars back and forth because it's so expensive and even trying to use Marta to get out there was just too much.

So I wasn't making anything. And I really believe that true artists, when they don't make work, they get sick because all that stuff is trapped inside of you. You know, you got to get it out. And sometimes it just helps to cover yourself in paint and make a mess right? Just make stuff.

So I ended up moving into a bigger apartment in Smyrna with a garage attached. Now my whole apartment is pretty much a studio space and I’m much happier. I can wake up and tinker in my pajamas if I want to make stuff.

JW: What are you working on now?

MM: Right now I'm currently building for a show at Eyedrum that’s opening April 8th, and I decided to bring on a collaborator – David Clifton-Strawn. He's actually the photographer who took the billboard picture for SPANKBOX. He's awesome. I met him because he was doing a studio project where he was shooting artists and he just made me so comfortable that I showed him some of my scars. I think he took a really powerful photograph of me.

To be clear SPANKBOX is not my project – it’s a project created by performance artist Jessica Blinkhorn, who is a quadriplegic, I would say. I’m not sure she considers herself to be a quad or not. She has a rare form of muscular dystrophy. She was born with it, and the doctors told her she would die when she was in her thirties. She's now in her forties, and she's just one of those spitfire people – she's fierce. She created SPANKBOX as a way to have a conversation about disabled sexuality because she – I guess a number of people asked her if she had sex, right? And she was like, “Of course I do.” Like, that's a basic human need. Everybody does. So as a way to encourage visibility for disabled people, she asked specific people to have their photograph taken.

JW: Ok, very important work.

MM: Right. So, David Clifton-Strawn and I have been working on a piece with a Shibari artist, and they have been tying me up in neon rope and lighting me with black light to create a series of photographs to express my frustration. I've always been incredibly independent, I do everything myself. And now – I had to admit that I need help - and that was really hard to do. “I don't need help. What are you talking about? I can do all the things myself.” But now it's different, I definitely need help, and that's a way of expressing my frustration.

I was talking with Gillian [Gillian Anne Renault] from ARTS ATL, and she was like, “So are you a performance artist now?” I've always hated performance art! I think most of it is obnoxious. It's like people get up there and they're like, “Look, I'm naked. It's art.” You know? I feel like that only really flies in a space where being naked is taboo.

But I think that this conversation is about disability – and specifically about visibility. I don't think that people see disability – and I think one of the reasons is that the world is not set up for disabled people to easily navigate it, so they don't leave their houses. So you don't see a whole lot of wheelchairs.

JW: That's powerful. Can you explain what Shibari is?

Visionary Mode, 2023. Photographs, sculptures and projections, Megan Mosholder and David Clifton-Strawn. Photo by David Clifton-Strawn.

“’Visionary Mode’ is a visual metaphor expressing my frustration with my perpetual recovery and permanent disability, resulting in lost relationships and opportunities due to what I assume are ableist notions of what it means to be a capable and independent individual. The only viable solution I found to deal with all these issues was to make art about it, using my usual medium of rope and light. My experience of exposing my scars while also making the choice to be confined by rope is just one more step on this long journey toward self-acceptance and empowerment. These photographs are a reminder for myself that only I can stop me from being successful in this life." – Megan Mosholder

MM: It is a Japanese bondage style. It was originally created by samurai, but I don't know why. I don't know why the samurai started tying people up, but they did. And it is just really beautifully executed.

My project isn't about sex. My project is about my physical disability and my immobility – and maybe it is a little about sex too, because I haven't been intimate with anyone since before my accident, because my body is so changed and disfigured, and I'm still learning how to get used to it myself.

I think the act of getting naked in front of a bunch of people who are then tying me up has helped me to conceptualize what it's like to be in the public eye and expose more of my body and my scar tissue. Previous to that, I was always running around in miniskirts and in heels.

But then it changed because, like it's been hard for me to look at because it's just so – I mean, I was burned over 60% of my body. What wasn't burned was cut off and then put on the burnt part. I mean, it's pretty epic. Like they had to cut muscle away. Then they were going to take both my legs above the knee, which I'm really glad they didn't do. They didn't expect me to live.

When I first came home from the hospital, I was sitting in the shower – I had to bathe to get the bandages off because they would adhere to the scabs – and it just hurt. I would sit in the shower and just rivers of blood would come off my body. Pretty intense.

JW: Yeah. Very.

MM: Yeah. I actually just started seeing an acupuncturist, and she's helping me process the trauma. Because I don't remember the car fire. All I remember is getting in the car and then waking up in Grady Hospital like a month later, which I wasn’t totally cognizant of that either, because I was on so many drugs.

JW: I read that you had times where you were hallucinating in the hospital.

MM: Oh yeah. I thought my doctors and nurses were having parties in the room next door. I could hear them snorting lines and stuff. And my mom would come see me, and I was like, “they were partying all night, mom.” And of course she’d go and talk to the head nurse and she’d be like, “Um, no,” you know, “we didn't do that.” They also nicknamed me Houdini because I was constantly pulling tubes out of my body. I was like, “I'm leaving. I'm getting out of here. I don't want to be here anymore.” And they literally had to strap me to the bed because I was trying to escape.

I used to drift in and out, and I'd come back to whomever was visiting with me and I'd say, “I'm sorry. I was traveling.” It was wild. At one point, I had this kind of circular vision where within the circle, I could see what was actually happening. But in the periphery there was some totally different thing happening.

It was really weird. I mean, I was on ketamine, fentanyl, opioids – all the drugs.

JW: Okay. Wow. So yeah. Is that what was causing that hallucinatory experience?

MM: Absolutely. I was in a medically induced coma, too. I think that's important to note, because, I mean, I had just incredible dreams – brought on by the hallucinations, I’m sure. It was just wild. I was seeing demons lurking in the shadows that were trying to get me. It was nuts.

And nowadays I'm trying to sit with burn survivors at Grady as a way to help them with their recovery. And, you know, some of them are telling me some crazy shit and I tell the nurses, “they said this is happening.” And they're like, “Oh, no, that's not happening. They're just hallucinating.” I'm like, “Yep, got it.”

Sorry. That was a lot, huh?

JW: Well, I didn't want to bring this stuff up if you didn't want to talk about it. But I really appreciate hearing what you have to say.

Ad Astra, (interior detail) 2022. Steel, mirrored stainless steel, light and paracord. 492 x 216.” Photo by David Batterman.

“At the beginning of January 2021, I was commissioned by the Microsoft Art Collection to build a permanent, site-specific sculpture for their new office space located in Atlanta, GA. Ad Astra is 41 feet tall and is constructed out of steel, mirrored stainless steel, light and paracord. The new Microsoft campus was the original location of Atlantic Steel, a manufacturing plant located in the heart of Atlanta for almost 100 years. Closing in 1998, the plant affected more than 300 jobs. Today, Microsoft is bringing jobs back to the city but now with world-class environmental sustainability, which says a lot about the continuing reincarnation of the city of Atlanta. “Ad Astra”, Latin for “to the stars” not only represents Microsoft’s contribution to Atlanta but all the possibilities the major corporation represents.

This sculpture is dedicated to my best friend, Erin “Peach” Arthur, who died at the age of 45. Peach was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer at the beginning of the Covid quarantine (April 2020) and was actively dying while I was creating the drawings for Ad Astra in March 2021. Her death has left a hole in the hearts of countless individuals. This sculpture is a testament to her memory.“ – Megan Mosholder

MM: I don't mind talking about it, because I think that through talking about it with other people – I mean, I've had so many people tell me that my recovery has inspired them with whatever struggles they were dealing with, and are dealing with or have dealt with. You know what I mean? So, you know, I feel like it's larger than me. It's definitely a part of my narrative now. Gillian from ARTS ATL wanted to know if I was concerned people were going to know me more from my accident than my art. And I was like, you know, I feel like it all kind of ties in, literally. I think that the accident is something that will always be there, obviously, but will start to lose volume. It won't be the thing that pops up first, if that makes sense, because I don't intend to stop working.

JW: I think it's really beautiful, the different ways that you're approaching things post-accident, there's just something really important about the work that you're doing.

MM: Thank you.

JW: But it isn't foreign to what you were doing before, you know? It’s like, you’re the same person - in fact, maybe, it even feels like it's becoming more monumental.

MM: Mm hmm. Thank you. Yes, that's something that I've always said. I'm still the same person, I'm just enhanced, I guess.

But it's been interesting. I feel like my community in some ways has had more trouble accepting it than I have, because they're used to this certain type of Megan. Like when I moved down to Atlanta from New York, I started wearing stilettos – this is a stiletto town – and my stiletto days are over. I don't know that my short skirt days are over, but definitely the stilettos.

I don't see me wearing four and a half inch heels ever again. And I'm okay with that. But in some ways it was harder for other people to deal with my accident than it has been for me. And maybe that's just because of the type of person I am – I'm not one to dwell on things.

I’ve always battled depression. And one of my ways of tackling depression is, you know, you’ve got to pick your ass up and keep going. You know, you’ve got to move. I think what's different now is I'm more kind to myself in that sometimes you just need a day to just be horizontal, watch a bunch of dumb movies, and then the next day you get up and go back to work. But never stop moving. It's like when people retire and they die three years later.

JW: Right.

MM: You know, it's like they've been busting their ass their whole life and now they're done, and the body’s like, “okay, we're done too.”

JW: Yeah, I know. I mean, like you said earlier about artists when you stop making, you get sick.

MM: Have you ever experienced that?

Photo by Ben Goldman

JW: Oh yeah, many times. Last year was so intense, there was so much work that needed to be done, that when it ended I was like, oh god. My body could feel it. It was like there was this illness that had been hiding in my body, waiting to come out all year.

MM: Right! Well and then sometimes you're like, “What is wrong with me?” And you're like, Oh, I haven't rested in like three months. Like, no wonder. Right?

JW: Can you talk a bit about the importance to you of creating a team?

MM: Hmm. I think that when I'm trying to build a team to make something, I'm trying to find personalities that gel well together, because a lot of what they have to do is be really on top of one another. And if you hate the person you're working next to it's not going to work. Also, I need them to be able to understand what I'm doing as an artist in a way that they can make informed decisions on their own.

The Google piece was really complicated. It was during quarantine. We were in Pittsburgh and – it was cute – some of my assistants had never seen snow before! So we had a snowstorm and they were ecstatic!

So I have one assistant who's been working with me ever since right before my accident. He's actually traveling with me to Los Angeles and he's kind of like my right-hand man. His name is Lucas Rocheleau, and he just gets it and he gets me. He knew me before the accident, and he knows me as I am now – so he understands how much help I need.

JW: Before your accident, were you doing a lot of the work? Did you have groups of people helping you then as well?

MM: Typically not, because my budget didn't allow for it. So, for instance – I mean, this was like weeks before my accident. I had just started teaching at Kennesaw State, and I was working on a piece in Madison, Wisconsin at the Botanical Gardens, which I kind of paused to fly home, start my classes at KSU, and then flew back to finish the piece. I also had a show in Brooklyn that I had to hurry up and make some work for. The show was kind of sprung on me and I was like, “Absolutely, I want to do that.” And also flew back to Tulsa to both tell the fellowship [Tulsa Artist Fellowship] that I wasn't returning and to move out of my studio space – I had a coveted studio space with a garage door that I didn't feel was fair to sit on, since I wasn't using it beyond storage. That was all in like four months, that I was doing all that. I was also working on various proposals, working on a piece I was installing for a design firm at the Renaissance Hotel in midtown Atlanta. Also at that time I was working on an event for Audi and that’s when I crashed.

I learned that your body will shut down. If it's tired enough, it will just shut you off. That's what – they think I fell asleep at the wheel.

JW: That amount of work is immense.

MM: I was trying to dig myself out of another black financial hole that I feel is sometimes common amongst artists, right? Because you need the time and the space to work – and that takes money. Often I've been able to find studio space before I found a living space. In Brooklyn, I lived illegally in my studio for a minute and almost immediately got busted. I mean, I've done that here in Atlanta, because the work has always been the most important thing, you know? And if you don't have a place to work – I've managed to figure out ways to make work, I've built stretcher bars in bathrooms before and been sketching or drawing or whatever on trains, planes and automobiles, you know – do whatever you’ve got to do to get it done.

So yeah. And then of course, I couldn't do any of it when I wrecked. I actually was in Grady Hospital and I was working from my hospital bed, because I had an installation that had to get done or it was like I had to give them the money back.

And it was like – the money was gone, right? So I had to hurry up and figure out a way. And I had friends and assistants step in to help me make that work. And I was, you know, talking to clients and making drawings from my hospital bed at Grady. But I think having that project really saved me and helped get me out of that bed, because it was a struggle.

JW: Looking at your career – there's no break. Every single year you have these immense projects. Which project were you working on in 2019 – during the accident?

Skylark, 2020. 480 x 81 x 144.” Hand-painted rope illuminated with black light. Photo by David Batterman.

“This installation was commissioned by the Rangewater Real Estate Firm. I built this permanent, exterior installation for both the residents of Skylark and the surrounding Chosewood community. During the creation of this public artwork, I was an artist in residence and I both lived and worked in the community.”

– Megan Mosholder

MM: That was the piece that was installed in Platform Apartments on MLK. Oh, and it's a daylight piece, which I haven't made another like that one. It's white twine that's been hand-painted with acrylic, and the way it's installed, the color is highlighted when the sun moves across it.

My folks took me to go see it – pretty soon after I left the hospital, so I was still pretty badly damaged. But they came out to tell me how much they enjoyed watching it transform throughout the day. Which of course made me feel really good.

It was the first time I had done anything like that, where I had hired a team and I wasn't there on-site working alongside of them.

JW: Yeah, was that scary?

MM: Yeah, it was. But, you know, I've learned that you do yourself a disservice when you get all freaked out about a project. You know, It's like, it has to get done whether or not you're freaking out about it, and it's easier to make decisions and problem-solve when you're not having an anxiety attack, you know?

So I've just really learned to take people's talents and apply them and work with them to problem-solve. I think that being a teacher has really helped me do that work with people. I acknowledge that they come to me with their own set of skills and talents. So if they have a better way to do something, I'm always open to that concept. I've seen assistants come up with really effective problem-solving.

JW: You were talking about the light shining through the piece, and obviously so much of your work is about light – you’ve mentioned the gloaming…

MM: I think one of the reasons why I'm obsessed with it is because I've spent so much time studying painting, and I think that's something that painters do – we chase the light. When you think about oil painting and how the old masters applied tints to build up the shape, the light is supposed to pass through some of that transparency so you can see what's behind it. I remember talking with Pheoris West about painting and he said that you really should only use a limited palette because having different colors will tie the painting together, and I feel like maybe light does the same thing.

###

more stories from impact magazine…

Jessica Leigh Lebos’ 10 Favorite Bull Street Art Stops

###

more stories from impact magazine…

more stories from impact magazine…

For the past 25 years, Jerome Meadows has been a staple of Savannah’s art scene. Hailing from New York City, Jerome first came to Savannah in 1997 to work on a public art installation for Yamacraw Art Park (much more on that later). His notable public art installations include the African Burying Ground Memorial in Portsmouth, New Hampshire (2013) and the Ed Johnson Memorial in Chattanooga, Tennessee (2021) – both of which called on the artist to honor and unpack a community’s history of racial violence.

Most recently, Jerome unveiled an installation at Savannah’s own Enmarket Arena titled “Of Communities and the Land and the Trees that Bear Witness to Them.” In addition to his public art installations, I’ve also seen his collage work and smaller sculptures in galleries all around town, and read about his passion for revitalizing Waters Avenue corridor, a majority Black neighborhood on Savannah’s east side and the location of Jerome’s studio. The studio – a 7,000 square-foot former ice factory – was easy to spot, and I arrived excited to interview the artist I’d heard so much about and see the place where he creates.

Meadows in his Waters Avenue studio, 2023. Photo by Emily Earl

Jerome greeted me near a purple set of double doors and welcomed me inside, shutting the warm Savannah air behind us. The front room looks like his work space featuring a few completed works of assemblages covering the walls. To the left is Indigo Sky Community Gallery, a cultural gathering place for art and performance that Jerome owned and operated from 2004 to 2018. I find the real treasure, however, after he leads me down a slim set of metal stairs.

This room is cavernous. Light comes in through several high placed windows and the vines of a tree have made their way inside. He had an industrial crane installed to help him lift heavier pieces; and the hook hangs from the ceiling to rest chest level in the center of the room. Large pieces of art – some finished, some in the midst of being repaired – are littered about. Two beams of iron are bent into a semicircle by chains and held in place by the weight of a large stone. Jerome places a hand on it and pushes it gently, making it rock back and forth. I see more stone figures than I can count. The space is still a factory of sorts, though today, it manufactures art instead of ice.

In this interview, Jerome talks about discovering himself as an artist during the civil rights movement, partnering with communities on public art installations, and how he feels called to create work outside of the ivory tower of galleries and museums. We talked about his frustration with the Yamacraw art project, and I learned about his love/hate relationship with what he calls the city of “Slow-vannah.”

Ariel Felton: Let’s start at the beginning. Do you recall what first called you to create?

Jerome Meadows: My first recollection of doing art is kind of a paradox. I'm living in the Bronx, New York City, on the sixth floor of a tenement. It was a rather cavernous kind of environment. I'm about five or six years old, sitting at the dining table, hearing the train go by every 15 minutes, and drawing horses. [laughs]

There's no horses around and I'm like, obsessed with horses. I've got them talking to each other. I got them running across the plains, and they're fairly representational. It wasn't until later that I realized – wow, this is the power of art, to enable you to divorce yourself from a situation or space that you don't feel connected with.

I also became infatuated with Michelangelo. I was really impressed by what's referred to as his slave series. It's these massive blocks of stone, and his style is very muscular and anatomically correct. These figures seem to be struggling to get out of that block of stone. His philosophy, his objective as an artist, and as a sculptor in particular, is to look at the block of stone and see that figure inside of it, and his job is to release it. But conceptually, that resonated with me in terms of New York City. The sense that it's a struggle to be who you are. All of this was adding up to me as a youngster in this city and realizing it’s not really where I feel at home.

AF: I read an interview where you said that Rhode Island School of Design is “where race and art came together” for you. Could you tell me more about that experience of formalizing an art practice that you discovered so naturally?

Sculptures in Meadows’ studio, photo by Emily Earl

JM: At RISD, there was such a small number of minority students; and when I say minority, not just Black, but Native American, Asian. RISD had been remiss in their diversity. Prior to us coming in there it was 1%. So the federal government said, ‘look, to the extent that you're expecting federal funds, you need to boost this up.’ This was during the ‘60s Civil Rights Movement, so we’re hearing this phrase a lot: ‘if you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem.’ So we were more inclined to look at other artists who were fighting the cause. Baldwin was a major hero. We're students, yes, and we're developing ourselves as artists, but at the same time always hearing ‘if you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem.’ It was a time for civil unrest and correction, but it's in the context of an art school and developing as an artist.

AF: You seem particularly drawn to public art. Why is that?

JM: If I spoke to 10 gallerists in a week, nine of them were assholes. And this stood in stark contrast to public art projects. If there were 10 people [working on a project], only one of them was an asshole, and he would be thrown out of the room. [laughs]

The other benefits, of course, are working large, being paid a significant amount of money and then the finished piece is placed outside in a public setting, which is the opposite of the ivory tower, where your work goes into some place and only a handful of people see it. I kept going back to that statement: the solution vs. the problem. Here's how I can make a difference with respect to my work speaking to the public, and all the public art projects I’ve done have all been along those lines.

AF: Was there a moment early in your career that you felt ‘wow, I’ve made it. I’m the artist I want to be’?

JM: Oh, sure, but it was a roller coaster ride to get there. This may sound silly, but I used to get up and go out to be involved in rush hour traffic, because I wanted to remind myself of what it is that I have been able to avoid – working a 9 to 5. Part of me kept thinking at some point the floor's gonna go out on the ‘being a full-time artist’ thing. But the mantra that I have is ‘Money follows passion.’ If you want to be an artist, that's your calling. Be passionate about it, and the money will come. The tricky part of that, I equate it to standing on a cliff. And the opportunity you're looking for is up there. It takes wings to get up there. But the irony of the situation is you have to take the leap for your wings to come out. That’s the only way you’re going to get up there.

AF: That’s quite a leap of faith!

JM: [laughs] Yes, but I'd rather risk the splatter!

AF: What if the wings don't come out?

JM: Well, the thing about wings is they only come out when they're needed. They're not just for show, or to prove something to somebody. They come out when they're needed. Those philosophies and assistance from the ancestors have made it possible for me, for decades now, to be a self employed artist living in his 7,000 square foot studio. Every morning, I decide what I'm going to do. I’m really proud of that.

Primary Circle, Ed Johnson Memorial, Chattanooga, Tennessee. Photo courtesy of the artist.

AF: Let’s talk about the African Burying Ground in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. In 2003, construction workers discovered the remains of eight individuals determined to be of African descent, shocking the community and motivating them to honor this uncovered history. Can you tell me how you honored the community’s wishes and still brought in your own style and voice?

JM: It’s a matter of trying to open myself up to the story. One of the good things was that the people of Portsmouth - and I should point out [Portsmouth] is 92% white - instead of them saying, ‘oh, this is fake news, down with Africana Studies,’ and all of that nonsense, [laughs] they said ‘wow, this is a part of our history. We need to do something about it.’ They raised $1.2 million in a relatively short amount of time, and this is the kind of openness that I was dealing with when I would talk to people about the story and the project.

The piece is about the first enslaved African man brought into Portsmouth in 1645. The formal entry has a granite wall. It's about eight feet tall, four feet wide and nine inches thick. On one side of that wall, standing on the edge, is a male figure. He's looking down into the memorial, and his hand is around the edge of that granite wall. On the opposite side is a female figure. He represents that first slave coming in. She's representing Mother Africa and she's reaching around the same side. I created these here in the studio and I'm struggling with whether or not the hands should touch, so I took it to the committee. They surprised the hell out of me! They said ‘oh, they should not be touching by about an inch.’

That's the degree of connection that public art affords me. I don't know if every artist has that. Because the committee is saying, we know what we want by way of concept, but if we could do it as artists, then we wouldn't need you. So we need you to come in and take that concept and give it meaning, give it expression. That was a perfect example of how that teamsmanship works.

Portsmouth African Burying Ground Memorial Park, with flowers. Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Photo courtesy of the artist.

AF: How would you say your style has changed over the years?

JM: I’ve learned that bigness isn't my thing. Rather than going 30 feet tall, I prefer to go 30 feet horizontal. Rather than something that's big, that you crane your neck to look at and it feels off-putting and separated, particularly with Martin Luther King and people who are about the people. When it comes to sculptures of individuals, psychological and emotional connection is stronger when you're on eye level with that person or that character. That’s a stylistic thing that I didn't necessarily start out intentionally doing, but it just seemed to be the logical way of approaching public art.

AF: What did you expect to find here in Savannah’s art community and did it live up to your expectation?

JM: I had no idea of what to expect, but I was not expecting Slow-vannah. I was misled because in that first meeting about the [Yamacraw art] project, everybody was there: the city manager, the mayor, and council members. I remember distinctly that we couldn't start until a certain individual gave his approval, and that was W.W. Law. Literally we sat there for about 45 minutes waiting, but fortunately, he called in and gave it his blessing. That should have told me something, the fact that it took that long. But I was compelled by the fact that the ocean is 20 minutes away, this building was what I needed, and then a handful of friends who already lived here. It’s been a love/hate relationship to be perfectly honest with you.

Portsmouth African Burying Ground Memorial Park. Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Photo courtesy of the artist.

AF: The Yamacraw Art Park project that brought you here was vandalized, then allowed to fall into disrepair for about 20 years. How does it feel to have it finally restored and the art park renamed as an official square? I imagine that was another roller coaster!

JM: Well, let me qualify that roller coaster was one in slow motion. [laughs] At this point, I've pretty much gotten over the anger and frustration that [the piece] was allowed to be neglected and in many ways, I'm seeing it new. For example, those plaques were always supposed to be bronze, but [due to the budget, they were] turned into aluminum. So the aesthetic wasn't there and they were very easily vandalized. So now finally I've seen the bronze panels, the banner supports and everything is clean.

I'm quite honored to be a living current day designer of a Savannah square. I would hope that this project and the new square will provide some positivity. It does in terms of children. The reason why there's three children dancing in that fountain is pretty much every time I would go over there and sit just to kind of feel out the space, these children would show up. And it was interesting because right after the dedication, there were children playing in the fountain. So for a community, the children are our future.

###

more stories from impact magazine…

Par for the Course

Phil Musen, Cats at the Bar. Oil on canvas, Courtesy of the artist.

My dad loves golf and he’s never had cable TV.

When I call him, I sometimes hear the clatter of a barroom and its TV bouncing off a wall into his speaker phone, because he always answers on speaker phone. Once a year, I hear a familiar piano melody that sounds like a pill commercial jingle trying to down-play its side effects. My dad and I talk on the phone a lot, but usually only for a couple minutes each call.

“Are you watching the Masters?” I ask him.

“Yeah, it’s the last day.” He yells this into the phone, thinking I won’t be able to hear him because he can barely hear me. I can almost see his eyes not move from the screen as he tilts his head towards the device. He doesn’t ask me how I know what he’s watching, but I assume he thinks I follow the PGA schedule despite decades of sharing my disinterest.

“I have some records by the guy that did that theme song.”

“Hmmm,” and the way he hmmms tells me now someone is swinging a club and he only almost heard me.

I tell him about the Dave Loggins records in my collection, how Dave Loggins had a hit called, “Please Come to Boston,” from his Apprentice album, and that another song on that record, “Sunset Woman,” I recorded with Larry Jon Wilson for his final album as part of the “Whore Trilogy.” I could tell he wasn’t really listening because usually when someone says the word “whore” people start to pay attention, no matter the context. I kept talking. I tell him that Larry Jon did a TV theme song, too, for a public access-type show called Georgia Backroads, and wasn’t it weird that two songwriters who made so many great records would be known to most people only because of TV theme songs that took place in Georgia? I reminded him who Larry Jon was since it had been a few years.

“Actually, Loggins’ best record is probably Country Suite. Larry Jon recorded “Goodbye Eyes,” too, but that was from One Way Ticket to Paradise. I keep forgetting we did two Dave Loggins songs for that record.”

“He must be good.”

Larry Jon would refer to Loggins as, not good, but a “heavy hitter.” It was a phrase he reserved only for the greats. The TV got louder, and it sounded like a car commercial, my cue for a more present conversation about something he doesn’t care about.

“You remember when I went to the Gulf Shores to do that?”

“Yeah, I remember. He was your friend that passed away that you helped make that record. These guys get much money for that, you think?”

“What, from their records or the theme songs?”

“The theme songs!”

“I mean…” I begin to share, pausing to consider how much energy it is going to take to make my point and if it’s even worth it, “no idea, probably some money, but imagine writing all those songs and guys like you all around the world scheduling their lives around a TV to watch golf and you all hear his music, but you’ve never heard his records or, probably, even the Three Dog Night cover. It’s like all these sub shops with their “Enjoy Every Sandwich” signs and these suburban moms with “Dance Like No One Is Watching” t-shirts. Warren who? What’s ‘Desperados Waiting for a Train.’ No one ever thinks about it. It just sits there.” I knew he didn’t know what I was talking about, but I also knew it didn’t matter.

“Seems like they should have done more theme songs.”

And I can hear the piano again, cutting through the air clearer than an announcer or advert.

“Dad, what I’m saying is, don’t you think it’s interesting what seeps into people’s lives, what makes it further into the world, and what doesn’t? It’s totally random. Not representative of their lives or work at all.”

“Right, right, random,” he agrees. “Pretty interesting. Oooooooohh.” The last sound told me someone swung a club and it didn’t go well.

“There’s actually words to the song, but the Masters just use the instrumental version.”

“It’s good this way. Doesn’t need words.”

He might be right. I can still see the Dave Loggins Lps in Larry Jon’s record collection. He only had a couple dozen records left when I met him, a few years before he passed, just two cardboard boxes on the floor. Buffett, Kristofferson, Loggins, Joe Williams, a John Hammond Sr. tribute LP on Columbia that Hammond had signed and given to Larry Jon. I remember the inked inscription being very sweet and I wish I had stolen that one. I didn’t have any Dave Loggins records then, but I bought them a few weeks later. They’re easy to find, usually a dollar or two, and when I see them cheap like that, I pick them up to give away, but I don’t think most of my friends like them as much as I do.