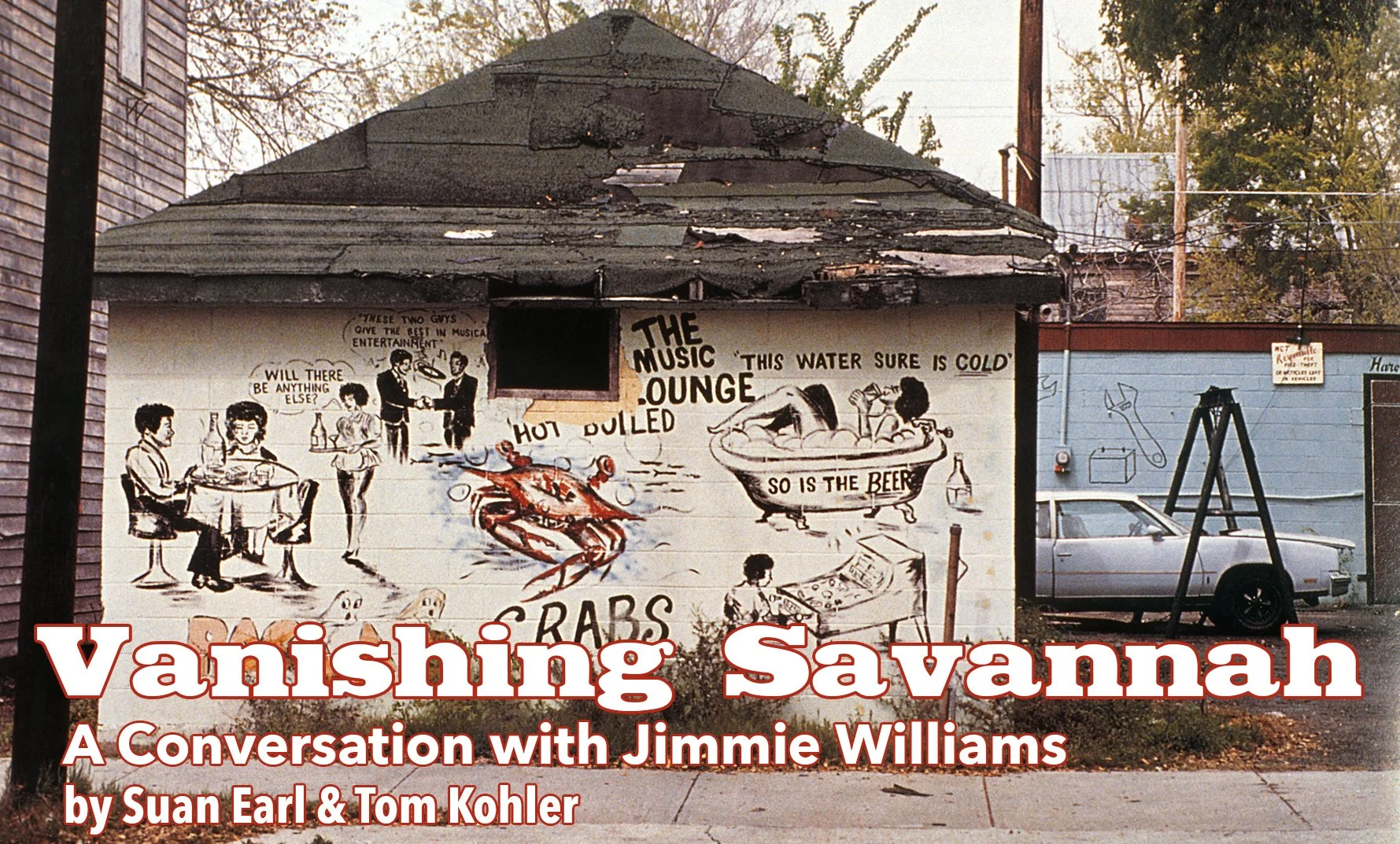

The Music Lounge, near Anderson and Jefferson St. Photo by Michelle Stewart

If you’ve driven around Savannah north of Victory, especially on Waters, Montgomery, or Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, you may have seen the work of Savannah’s most prolific sign painter: Jimmie Williams. Over the years he’s painted a wealth of images on Savannah buildings. You might not have known his name, but his beautifully rendered portraits and elegant free-hand lettering have always been unmistakable.

In the 1970‘s, 80’s and 90‘s, Williams’ distinctive renderings of dapper gentlemen, beautiful women, tricked out cars, tempting plates of seafood, and prayerful hands adorned churches, barber and beauty shops, clubs, restaurants, auto repair shops, and car washes all over downtown Savannah. As the area has gentrified, sprouting hotels and luxury hi-rises, most of these signs have vanished.

You can still see some of Mr. Williams’ signs, many faded, on the windows of Harris’ Barber and Beauty Salon at Montgomery and 40th Street, on the former Mr. Wonderful Bar across the street, Beaver’s Barbershop on MLK, Records and Tapes on West Park Avenue, the Rosette Lounge on Waters and East 36th, and on Discount Muffler on 32nd. Auto Painting Express’ colorful sign at 809 West 52nd still looks brand new, as does the sign on the Boyz II Men Barbershop, now vacant, on Bull and 39th Street.

But like the downtown signs, these too are likely to disappear.

An early and avid fan of hand-painted signs, Savannahian Tom Kohler routinely updated his scrawled list of locations as businesses changed over. As new signs appeared, we’d photograph them. With an upswing in gentrification, more Black businesses were pushed out and signs began disappearing or were covered over. During the 15 years we photographed signs, we collected hundred of images. Jimmie Williams’ work predominated.

Born in Savannah, Williams grew up in a large family in Tatumville, west of Montgomery Street. After graduating from Beach High School in 1965, he enlisted in the military and went to Vietnam. Honorably discharged, by 1967 he returned home and was working at a series of jobs, painting signs as a side business. By the 1970‘s, he was painting signs almost full-time.

We caught up with Mr. Williams in his west Savannah backyard and sat under his carport — a combination man cave and workshop — and listened to stories about his life and career.

At 75, he said, “I’m not the oldest man in the world, but I’m not the youngest. I come out here in the morning. I like to see the sunrise. It’ll be dark, and when I come out I like to see the sky break. Trees against the sky. If you’re not waking up in the morning, then what are you doing?”

And with that, he took us back to his beginnings.

Jimmie Williams, 2021. Photo by Emily Earl

Jimmie Williams: My mother’s name was Sarah Williams. She was a practical nurse. My father’s name was Thomas Williams. He did shift work at Union Camp. Our home church was Second Arnold Baptist. That’s the church I was baptized in at 12 years old.

One Christmas, my mother went and bought me little cans of paint. I was about nine or ten. I got one of them old pull-down shades, put it on a piece of cardboard, tightened it up. And I painted Jesus Christ the Shepherd with a lamb in his hand. My mother kept that picture until I came back from Vietnam.

In Haven Home Elementary School, a school for Black students only, he painted scenery with his best friend Thomas Hall. The school went from first to seventh grade and was located on Montgomery Crossroads. They had to walk there all the way from Tatumville, about three and a half miles each way.

JW: We’d go up on that stage, and we’d roll out that brown paper, and start going to work. “Oh man, we gonna make this thing pretty!” And from then on, anytime you had an auditorium program, or a play: Jimmy Williams, Thomas Hall.

Later, he went to Beach Junior High, then Beach High School.

JW: I was in the art club at Beach. I painted Whistler’s mother, I painted Mona Lisa, I dabbled at things that were hard to do. I played football and ran track at Beach. Those are three things that I excelled in.

Tom Kohler: Would you be willing to say something about your experience in Vietnam?

JW: It was hell. I can tell you that. One tour. That was enough. After I came back, I worked in a chicken house, icing down chickens, over there on East Broad and 31st. I started working at Union Camp for a company called Blunt Brothers out of Mobile, Alabama. Poured cement. I joined the National Guard. I painted billboards — fifteen and a half, by forty-five feet long for the Estes Sign Company.

I was over across the Talmadge Bridge on the South Carolina side with another painter. And we were on a scaffold and got stuck up on that sign in high tide. Tide came up so high, no way I was getting out in that water. By the time they rescued us that afternoon the tide had gone down and they could come and get the trucks out of the bog.

Jimmie’s hands made a space about twenty-four inches across.

JW: A walk board about that wide, that’s what we were stuck on.

TK: When was this?

JW: In the 70’s. I already had my own sign business then.

He pointed around his backyard.

JW: That’s why I set up this place back here to do my work, you understand? I set this up to accommodate the 4 x 8’s and those big signs. And I still worked on my regular job.

He took a cigarette out of a pack and broke off the filter.

JW: I’m gonna show you something. See this cigarette filter? Just like bristles on a brush.

He pulled some of the paper back, stuck the point of a pencil in the filter and handed the “brush” to us.

Photo by Susan Earl

JW: Man wanted a His and Hers bathroom doors painted. You know, a male figure on one door and a female figure on the next one. I went outside and picked up cigarette butts and painted with that. I painted beauty salons, barber shops, churches, murals in clubs. Anything that had to do with Savannah. I brought one of the first SCAD students here, and showed her a trick to scaling words and how to lay out a sign.

TK: One of our favorite of your artworks was a mural named Freedom Ain’t Free. It covered a whole wall on a building on Pennsylvania Avenue. Who commissioned that?

JW: I did. Along with the owner of the building. We had an agreement and signed the picture together. But I still don’t know who painted over that, today.

TK: Would it be fair to say it was it was painted over by no agreement?

JW: Yeah, that’s fair. Me and my wife painted that building. It was on the side of a barber shop near the new Savannah High.

Freedom Ain’t Free, Pennsylvania Ave, Photo by Susan Earl

TK: Why do you think it got covered over?

JW: Man, look at what I’m saying in that picture. I painted Harriet Tubman, Confederate and Union soldiers dying, slaves working in cotton fields, and a bullwhip instead of a torch in the Statue of Liberty’s hand. You got some haters that jump dead on that. They wanted to get that gone quick. Because it said too much. It was political.

TK: What other work of yours would you call political?

JW: Bad To The Bone. It was on a car repair place about two streets south of Victory. It sat to this side. I painted a Black man holding up the world. He was sweating and there were drops of blood coming off of him. I painted two pickup trucks on the same side of the building. I made the building windows look like the truck windshields.

Bad to the Bone, MLK and 44th Street. Photo by Susan Earl

TK: Tell us about your technique. How do you manage the brush? What do you think about when you’re painting?

JW: When I pick up a brush, I actually get lost. If I make a line, I go from there. If I make a mark, I work from that mark. If it takes me right, left, center, low, whatever. I work from that mark. But I try to work with perfection. I try to give you what you’re looking for. There’s no erasing. Especially when you’re working with a color like red, or blue, on top of yellow. I’ve been doing this too long. And any complaints I had, you can put 'em in a bucket. I never use low quality paints. Because they peel and they show your work up bad.

TK: What kinds of brushes do you use?

JW: You got some flats that carry long bristles. That’s for dragging and making complicated letters. They give you enough paint, but not too much, so you can maintain a drag with your stroke and then come back. It’s It’s sharp enough on the tip, that you can come back underneath. Then the rest ain’t nothing but filling in.

Jimmie picked up a brush with long bristles.

JW: For a script, I’ll use one about like that.

He waved it in the air like a magic wand.

JW: And whoosh, whoosh, whoosh, whoosh. It gives you enough paint to get you your stroke. You come back under it with the tip. That sharp cutting is what you wanna get. Don’t ever use a brush too short for the job.

He showed us a photo of one of his car paintings.

Montgomery Street. Photo by Susan Earl

JW: I start at the center. Top dead center. Make a line down there. I know what the car looks like. Paint the car in there. The guy’s a mason, I put the symbol up there. AUTO MART. Make it big and plain. You want it so when you ride by you can read the whole thing.

TK: Did you ever use aerosol cans?

JW: All the time. I’ve used contact paper, taped off, used a pencil and a razor, cut and taped and sprayed.

TK: How did you find work?

JW: It found me. I gave lots of people estimates, and some never called back. But a lot did. The ones that was about business. And I would respond to any job. I’d get a call. “Mr. Williams, can you meet me on 61st and so-and-so? I want you to look at a job.” I’d say, “Yes Ma’am, I’ll be over there shortly.” That’s the way I worked. People found me.

TK: Did you ever run into people who thought they didn’t need to pay for artwork?

JW: Man, I’ve been up and down the road with that. You know what I’m saying? I don’t mean to insult you. I’m a businessman. I give you an honest day’s work. All I want is an honest day’s pay. I don’t buy material for nobody’s job, because otherwise I’m digging myself in a hole. You furnish the material, I’ll furnish the labor. And then, I need half of that upfront and half when I’m finished. If there was a problem, it was getting that second half.

TK: Have there been other neighborhoods you’ve painted in? Sandfly? Coffee Bluff? Over in Pooler?

JW: You people in Savannah didn’t let me go nowhere. You understand, because they kept enough work right here.

Photo by Susan Earl, MLK & Bolton Street

TK: Now, when you were painting, did you listen to music or did you just paint quietly?

JW: I like music, man. I like the old school music. We’re talking the Four Tops, the Temptations, the O’Jays, and all that. Gladys Knight and the Pips. That put me in a mood.

TK: Do you think you’ve painted hundreds or thousands of paintings?

JW: I might have painted a couple thousand. All the things that I’ve done in this town, it’s hard for me to remember some of them. I’d be out here at night, sitting and drawing. My daughter bought me a voice recorder so I can record some of what I did. I did a lot of work for Geneva Wade, when her restaurant Geneva’s was over on Bee Road. I painted all the tables and the entire bar.

TK: Let’s see — the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s, into the 2000’s — you’ve worked for over 50 years. Are you still doing any jobs?

JW: Right now, you know my wife Joanne recently passed. We were together for forty-nine years. I never had nothing come up on me like this. It’ll walk up on you. It’ll tap you on the back and say, listen, you can’t do that no more.

TK: We can all relate. But you never know, right?

Jimmie smiled.

JW: You never know.

Photos of Jimmie Williams’ work have been displayed at the Sentient Bean, the Jewish Educational Alliance Gallery and in the Rotunda of Savannah’s City Hall.

###