The Do Good Fund, Columbus, Georgia

We sat down with Alan Rothschild, founder of The Do Good Fund, a public photography archive based in Columbus, Georgia. Since its founding in 2012, The Do Good Fund has grown into one of the most dynamic collections of contemporary Southern photography, with over 800 works by celebrated artists and emerging voices.

Rothschild reflects on the evolving nature of Southern photography and his deeply personal belief in the photograph as a tool for connection. From collecting his first image — Keith Carter’s Garlic — to building a collection that spans decades of Southern life, Rothschild has created a visual archive that captures the South across time. His work reminds us that photographs are not just aesthetic objects, but time-markers — connecting past and present, tomorrow and yesterday. They can be windows into how we live, who we are, and what we value.

Rothschild’s vision for The Do Good Fund is rooted in accessibility and storytelling. Works are loaned, often for free, to regional museums, nonprofit galleries, and even unconventional community spaces across the South. The result is a living, moving archive — photographs that don’t just reflect the South, but remain in conversation with the people and places they depict.

As the South continues to shift — culturally, environmentally, politically — the photographs in The Do Good Fund’s collection serve as vital documents of change, memory, and place. Rothschild calls them “visual stories,” and through this lens, the South becomes not just a region, but a shared narrative shaped by light, land, and legacy.

IMPACT: How did you first become interested in photography? Was there a particular image, artist, or moment that sparked your passion?

Alan Rothschild: My personal interest in photography is rooted in a high school Southern literature class which introduced me to Walker Evans’ Alabama tenant farmers photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Growing up in Columbus, GA in the 1960’s and 70’s, I did not have to go far to see the scenes Evans documented in the Alabama Black Belt a generation earlier. Majoring in history at the University of Virginia, I also realized that Evans’ work, or a Mathew Brady Studio image from Gettysburg told me more about the history of the region where I’d lived my entire life than many chapters of a history textbook.

IMPACT: The Do Good Fund was founded in 2012 with the goal of building a museum-quality photography collection of the American South. What initially sparked this idea, and how has the mission evolved over the past decade?

AR: I have always enjoyed going to museums and have long supported the ones in our region, including serving on the board of two institutions. That said, I once read that a typical museum has over 90% of its permanent collection in storage at any one moment. The idea behind Do Good was to build a public collection of contemporary Southern photography that could be loaned to traditional museums, community art spaces and even non-traditional venues for little or no charge – so that the work could be seen, not stored. As the collection has grown, it has become more challenging to keep work on the walls and off our shelves, but we have begun wider marketing of the collection’s availability and in April our first Do Good Fund Curatorial Fellow, Emily Rena Williams, will put together a turnkey exhibition, including all of the wall texts and exhibition guide materials, so that the host venue only needs to hang the work on their walls.

The continuing reward of Do Good for me is meeting so many creative and energetic photographers and curators – they are the ones who do the real work.

Alan Rothschild and IMPACT co-editor, Emily Earl in The Do Good Fund storage room. Photo by Jon Witzky

IMPACT: One of The Do Good Fund’s most unique aspects is its commitment to accessibility — loaning works to regional museums, nonprofit galleries, and even nontraditional venues. Why is this an essential part of the mission?

AR: The importance of this hit home to me during a show in Greensboro, Alabama, the county seat of Hale County, Alabama. Hale County is ground zero of Southern photography, in my mind, because it is where Evans photographed his famous images in the 1930’s, and where William Christenberry photographed his ancestral landscape for over fifty years. Standing in front of one of Christenberry’s images in the Greensboro show, the lady next to me walked up to the wall label, then turned to me and said, “I have known Bill (Christenberry) all of my life, but I have never seen his photographs.” Even though the Birmingham Museum has a large collection of Christenberry images, for this lady, Birmingham was no closer than New York or London, she was unlikely to get there to see the work in person.

IMPACT: What was the first piece acquired for the collection, and why was it significant? Did it set a precedent for future acquisitions?

Keith Carter, Garlic, 1991. Gelatin Silver Print, 15.375 x 15.375 inches, edition 21/50. Courtesy of The Do Good Fund

AR: When we started The Do Good Fund, I visited with Jane Jackson, then owner of Jackson Fine Art in Atlanta. I told her about our new project, including our our initial budget (which remains the same 13 years later…). She told me that we could not afford to collect Sally Mann or William Eggleston, but shared the names of three Southern photographers that she thought were extremely talented, yet undervalued in the art market at the time, Shelby Lee Adams, Debbie Fleming Caffery, and Keith Carter.

In researching their vast bodies of work, I came across Keith Carter’s Garlic. I was struck immediately by the beauty of the image – Carter caught the perfect moment, the female subject swinging two freshly harvested garlic plants into the sky. But what also caught my eye were the very modest clothes she wore, and the sliver of land at the bottom of the image indicative of one of the Southern deltas.

The image remains one of my favorites, a beautiful image photographically, but its simple composition belies a more complex story, of the subject herself, and the delta land she inhabits.

IMPACT: How does The Do Good Fund select works to acquire? What makes a photograph stand out as a worthy addition?

AR: For good or bad, our collection process is much more subjective than a typical museum with a collection committee and collection plan. But our mission is not to tell a comprehensive story of Southern photography, which might require a more formal approach to deciding who and what is added to the collection. Instead, we are a collection of visual stories of the American South. This allows us to collect diverse and interesting images from the region that we think complement other works in the collection and which, hopefully, viewers find informative and engaging.

IMPACT: Can you share a particularly interesting or unexpected story behind acquiring a piece in the collection?

AR: In the fall of 2021, we were contacted out of the blue by a New Jersey collector interested in donating a significant holding of Burk Uzzle’s photographs to the collection. I had long admired Burk’s work and had the privilege of meeting him at a Do Good show in Chapel Hill, North Carolina a few years before. Burk has had an interesting photographic career, he served two terms as President of Magnum Photos, the well-known international photographic collaborative, and one of his photographs, the cover image of the Woodstock album, is one of the most iconic images of my lifetime. A few weeks after the collector reached out, two large boxes containing nearly seventy Uzzle images arrived in Columbus. This is still the largest single in-kind donation Do Good has ever received.

IMPACT: Are there any recent acquisitions that stand out as particularly exciting or that fill an important gap in the collection?

Burk Uzzle, Alligator Farm, Florida, One Hand Left, Florida, 1979, Gelatin silver print, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy of The Do Good Fund

AR: As a result of a strategic planning session in 2018, we decided to focus our acquisitions on lesser known and emerging photographers. Six months after making that decision, we were contacted by a wonderful Arizona-based donor who helped us expand our emerging photographer holdings through an acquisition fund he established. To date, we’ve collected work by ten photographers through the Collinsworth Emerging Photographer Acquisition Award Fund.

IMPACT: Many of the works in The Do Good Fund’s collection depict everyday life in the South. How do you see photography as a tool for storytelling and preserving history?

AR: It has long been said that the Civil Rights Movement may not have been successful without cameras. Gordon Parks called his camera a weapon against poverty, racism and other social wrongs. Even though Parks’ Segregation Story series, first published in Life Magazine in 1956, featured domestic scenes and day-to-day life in Mobile and rural Alabama, his images told a story of the impact of segregation that was, and is, no less powerful than our Charles Moore’s image of three young Blacks pinned against a building by a firehose at a Birmingham protest.

One of the largest prints in the collection, Jeff Rich’s Blue Ridge Paper Mill, is a great depiction of both the beauty and environmental degradation that exist side-by-side in so many parts of our region. Between the forest in the foreground and Blue Ridge Mountains in the distance, clouds of steam or smoke rise from the plant, containing who knows what toxic substances.

IMPACT: How do the images in this collection challenge, reinforce, or expand the broader cultural perceptions of the South?

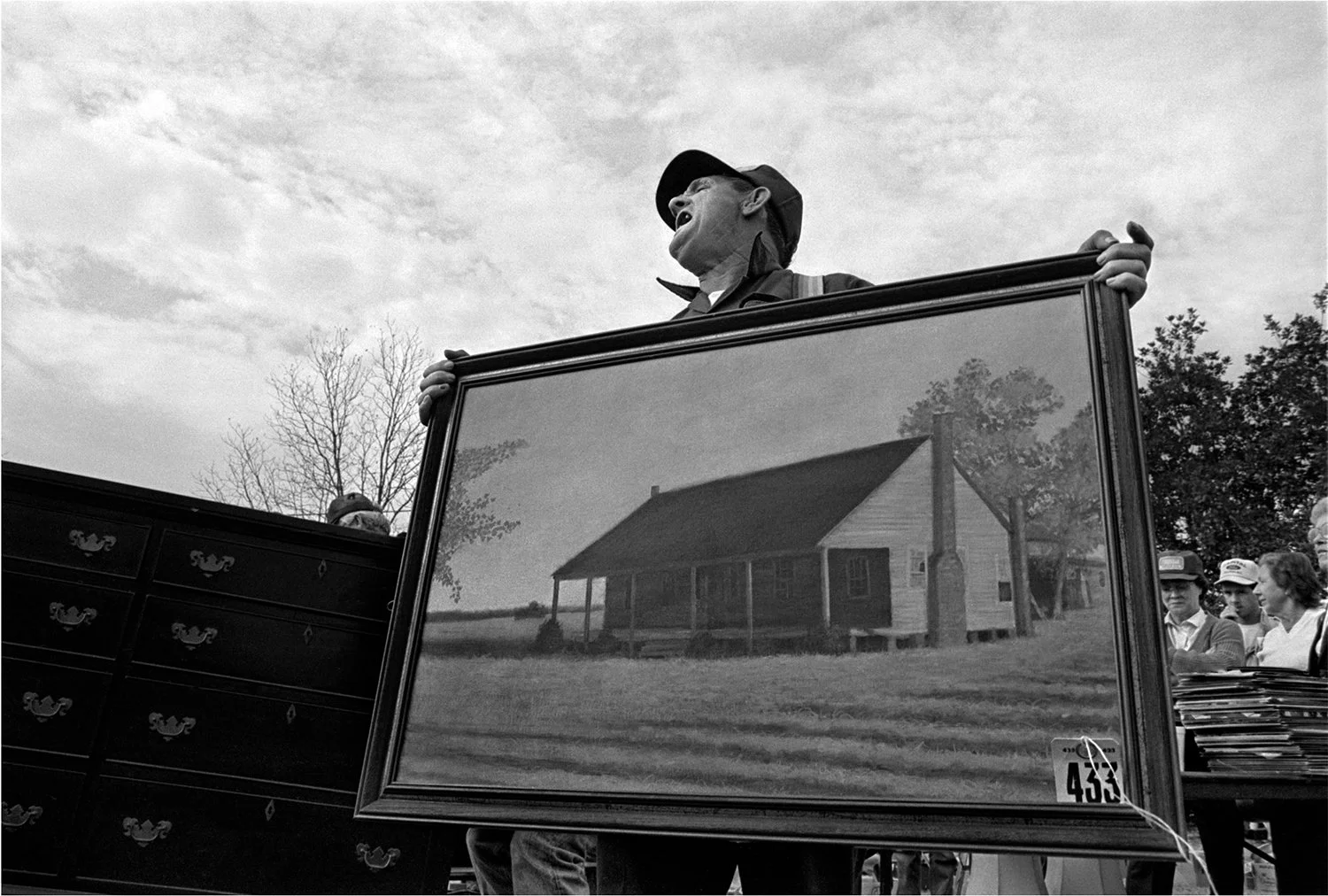

AR: In many ways, that’s a question for the viewer. A number of the images in the collection ask the viewer if the region is different from other parts of the country, and if so, in what way. On the other hand, Rob Amberg’s image, Estate Auction, Bishopville, SC, shows the impact of the population decline in rural South Carolina that would be familiar in rural Kansas or Oklahoma, even Canada for that matter.

IMPACT: How do you see Southern photography evolving? Are there contemporary themes emerging today that weren’t as prevalent when the collection began?

Gordon Parks, Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Archival Pigment Print, 14 x 14 inches, edition 10/25. Courtesy of The Do Good Fund

AR: It appears to me that photography is evolving universally. Everyone is a photographer today with their cell phone and the internet abounds with visual images. There are fewer and fewer darkroom prints being made, even if the image maker is still using a film camera.

We don’t intentionally collect themes, but most photographers working in the South today have gone beyond the stereotypes of the rural South. For example, one of the significant events taking place in the region is the continuing shift from the traditional rural landscape to more suburban and urban spaces. Joshua Dudley Greer’s image Gray, Tennessee is a great example of the environmental and aesthetic impact of this ongoing land use transition.

IMPACT: What impact do you hope these images have on viewers both those from the South and those seeing the region through these photographs for the first time?

AR: At its core, The Do Good Fund is a collection of visual stories of the contemporary American South. These stories are told by an increasingly diverse group of photographic storytellers, men and women, persons of color, from different regions and cultural backgrounds and sexual orientations. Stories about life and death, work and play, and urban, rural and suburban settings, from the Piney Woods of East Texas to coal mining communities in West Virginia and the clear springs and sandy beaches of Florida.

Rob Amberg, Estate Auction, Bishopville, SC, 1987. Archival Pigment Print, 8.5 x 13 inches, edition 3/20. Courtesy of The Do Good Fund

In my mind, most of the images in the collection are about, rather than just of, something - revealing a story in one way or another about the people or places of the region. What attracted me to Keith Carter’s Garlic was more than just the magic moment Carter captured of the woman swinging two freshly harvested garlic plants overhead, but also the style of her dress and fragment of landscape at the bottom margin of the image, both clues to a larger story just beyond the frame.

My hope is that the images in the collection will be viewed not only as worthy examples of the photographic craft, but also as a window through which to know more about ourselves and the place that we live. This is important, because as Eudora Welty said, “one place comprehended can make us understand other places better.”

IMPACT: Are there upcoming acquisitions or exhibitions you’re particularly excited about?

AR: It’s been awhile since images from the collection have been in Savannah, we are really looking forward to the May exhibition at ARTS Southeast [Tomorrow and Yesterday, Selections from The Do Good Fund]. Looking ahead, we are also excited to open and tour a show featuring Mississippi work by Maude and Langdon Clay, and their daughter Sophia. This show opens in The Do Good Gallery in Columbus in September, then travels to Ten Nineteen Gallery in New Orleans during PhotoNOLA 2025. We also have 2025 shows on the calendar at the Paul R. Jones Museum in Tuscaloosa, Vero Beach Museum of Art, and Gadsden Arts Center & Museum in Quincy, Florida.

IMPACT: If someone wanted to start their own photography collection, what advice would you give them?

AR: During the thirteen years Do Good has been acquiring work, I’ve realized that photographs are a lot like songs. The ones you like right off may not be the ones that stay on your playlist for a long time. When acquiring work, we look at the image initially, put it away, then pull it out weeks, months or even years later to make sure it still has the same impact as it did the first time we saw it.

###

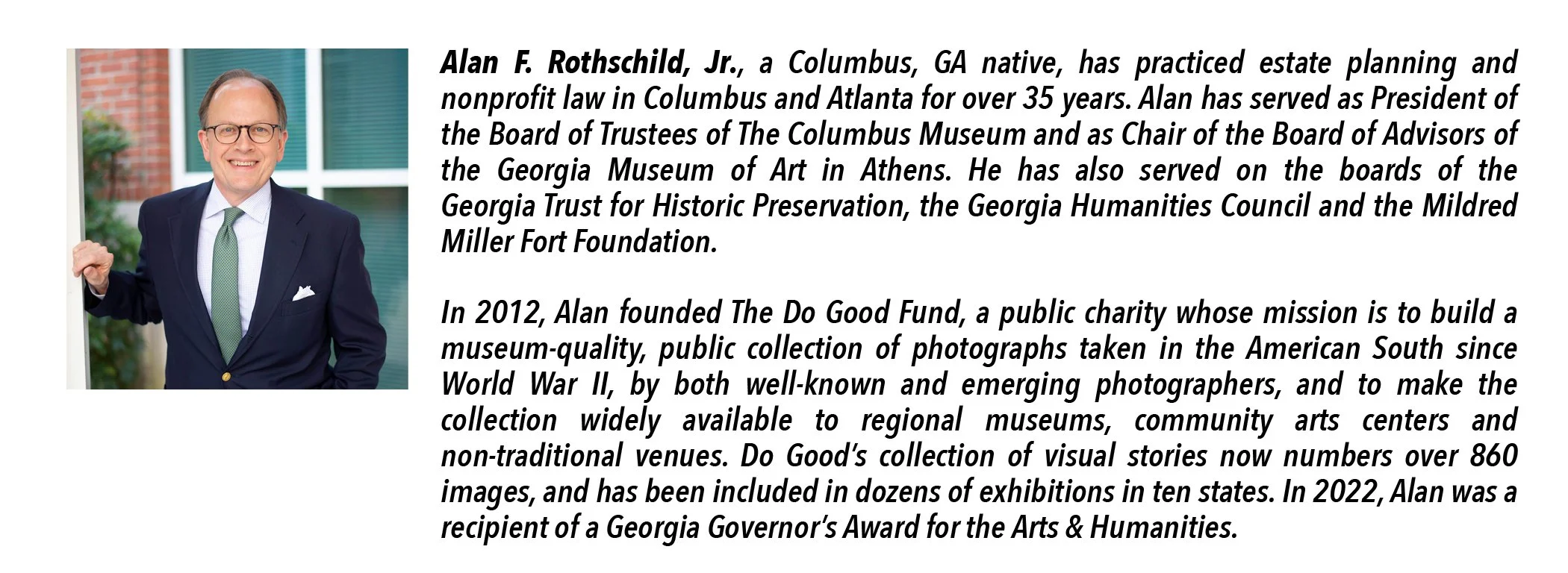

Tomorrow and Yesterday, Selections from The Do Good Fund was on view at ARTS Southeast in Savannah, GA, from May 2 – June 14, 2025. Learn more about The Do Good Fund at: www.thedogoodfund.org