Synchronicities: Intersecting Figuration with Abstraction (installation view). Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, 2025. Pictured with ceramic works by Liz McCarthy. Photo by Colin Conces

This spring, I was fortunate enough to visit Amy Pleasant at her studio in Birmingham and talk with her about her work, curatorial endeavors, and so much more. We discussed the evolution of her early paintings and how they developed into the forms we see today, her approaches to artmaking and curating, her trajectory as an artist, and how the South has shaped that journey. Amy was incredibly generous — welcoming us into her space and speaking candidly not just about her work, but her life as well, sharing stories of a young Lonnie Holley, her rich family history in the arts, and a deep reverence for her hometown of Birmingham.

It’s always amazed me how simple yet affecting Amy’s work can be. Regardless of medium, there’s a dynamic mastery in her use of fragmented figures. From working with a designer to translate her drawings into a custom typeface, to casting monumental bronze forms, it seems there’s nothing Amy can’t do. Beneath the surface of her subdued palettes and silhouetted shapes — evocative of Greek amphorae or Cycladic idols — are meditations on collective human experience, on ancient and prehistoric art, and on how our bodies shape and reflect meaning. While the work may appear stark at first glance, Amy imbues it with warmth, curiosity, and a quiet reverence for something larger than life.

Noah and Amy in her Birmingham studio. Photo by Michael Shepherd

Noah Reyes: I'm curious to hear about your process. I've read in past interviews, when approaching these fragmented bodies, they're not something you outline, but something you feel out in a fluid motion.

Amy Pleasant: All of my work comes out of my drawing practice. For me, that's how it always began, even when I was a young artist; everything came to me through drawing. It was in graduate school where I had that mind opening, where I realized what the drawing actually meant to my whole practice, and that what I was considering a peripheral activity was actually where the work really was. I needed to figure out how to take that into painting and other things later on.

It's important for me that I discover something or that something reveals itself to me. I may start with the intention of a shape or a gesture, but through drawing over and over and over again, a shape will become what it's supposed to be. I usually use ink and sable brushes because they're soft. There's a freedom of how they move. And then also with gouaches, I thin down gouaches until they're pretty fluid too, but also stay very opaque. I will tear up small pieces of paper — anywhere from four by five inches, four inches by by six inches — and I just draw. I try not to control it too much. It's when I let it open up and I just freely mark, that the shape will come to me in that way. And that's exciting. And then it's like, “Okay, now how can I take this into other things that I do?”

I was approaching my painting practice – going specifically back to when this awakening happened – I was thinking about my painting practice as a very different activity. I wanted to somehow merge those things. I know Amy Sillman talks about that all the time. It's like, how is drawing in painting? And for me, that's what I needed too. It became a similar process of me thinning oil paints down and getting some of that same fluid mark-making in painting.

NR: Looking at the work, it seems as though these forms you paint are carved out of stone. Despite the nature of paint, they can feel pretty sculptural. You've also cited being influenced by ancient art and artifacts. How much of that factors into things when you're making your work?

AP: I love that you sense that from the work, because it's funny how I'm interested in sculpture. I've always been a very two-dimensional artist, and even my sculpture is very two-dimensional — and that's kind of funny. But I do look at a lot of sculpture because I'm so interested in looking at ancient forms of artmaking, ancient forms of making representations of ourselves. So I know that is all in my head, even when I'm creating a flat silhouetted shape. For me, because I'm flattening out and creating a silhouetted form, it is simplifying sculptural shapes even more. Does that make sense?

Reclining Figures, 2022. Oil on canvas, 72 x 108 inches

NR: I think that makes sense – especially in the torso series that I've seen a number of, sometimes I think that the negative space of your works pop further out than the actual figures, and it's a pretty crazy trick or visual maneuver that is nice.

AP: I like that too, because it also slows down how you're reading the image. Because of the way I work, they can be very graphic and people think they know exactly what they're looking at right away, but then I love that slow reveal of something else, you know? Something else is going on. Some of the newer works, I'm playing with drawing the negative space or painting the negative space and allowing the grounds to actually create the shapes of the figure.

NR: Like the painting that's behind you right now? [laughs]

AP: Yes, exactly. And the first one that was also at the Atlanta Art Fair that I did for Whitespace [Gallery]. I love thinking about archaeology and again, how we're unearthing our history. The activity of painting the negative is very similar to the chipping away of the earth to reveal the object. I started thinking about that activity, and I love feeling like I'm digging these forms out of these grounds that I'm creating. So I've been doing a lot, especially recently, experimenting more with grounds and creating colors and textures that I can let the shapes emerge out of, which is exciting. So it relates to that very physical thing, or represents a very physical thing, but it's a two-dimensional flat surface.

NR: About archaeology, what are some of the influences that you're looking at lately in terms of this ancient or prehistoric work?

AP: Cycladic figures. The huge show that was at the Met is unbelievable. I’m looking at stuff all the time. Greek vases have always been a huge influence for me. Again, you have the silhouetted shape, you have the delicate line, you have the negative and the positive. Those works have always been important to my work. In terms of painting, I have this great used book I found of Arab painting, and it is incredible.

NR: To zoom out a little bit, you talk about a collective human experience that underlies all of these archaeological works or… they just feel bigger than any one person or civilization. How do you think about that collective human experience?

AP: I think about it in the sense that we're always looking for ourselves in the world. We're always looking to find ourselves reflected back. I think because we're always seeking meaning. I think that it is possible to find ourselves in any ancient works. What are all these activities that are similar that we do?

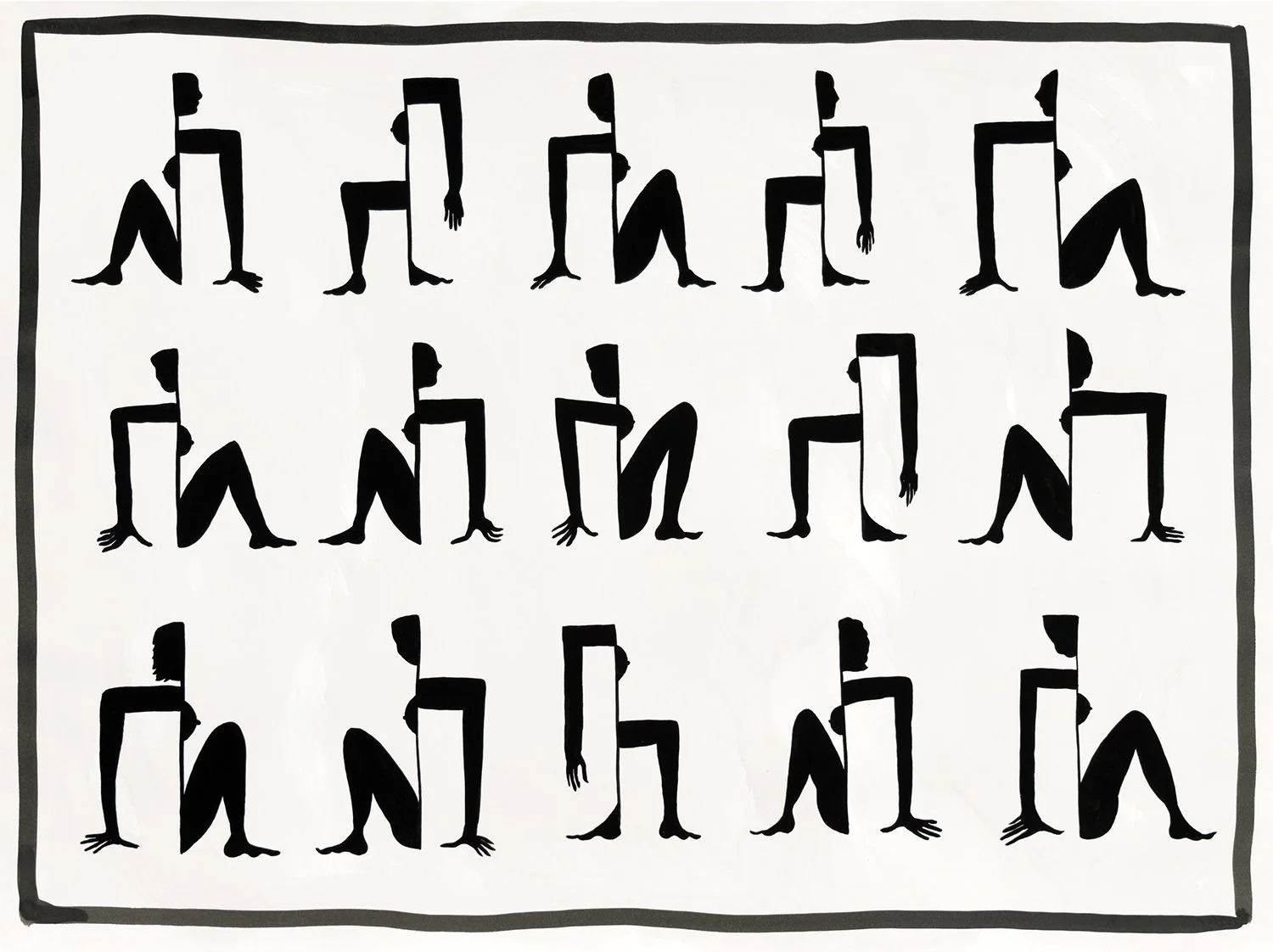

A lot of my earlier paintings coming out of graduate school were what I called my storyboard paintings, which were chronicling daily life, where I was trying to focus on these very ordinary activities — getting dressed or undressing, or getting in and out of bed, or a conversation two people are having, things like that, activities that we do that we don't even think about. And then later on, I began to strip away that narrative and focus on the figurative shape and the figurative form, and still be a simple gesture of a reclining figure, or somebody resting their head on their hand, or a way somebody is sitting, or the way someone's bent forward. And you can start to sense how that figure is feeling. And just looking for ourselves in all things. I think that's why we love to go to museums. I think it's why we love to look at those objects. It's because we're looking for ourselves in them. I think that's just a beautiful communion that we have with history.

NR: I'm glad that you mentioned some of that earlier work because I've been studying your work, trying to read everything that I can get my hands on, including some older interviews in Art Papers, which made me look back at when you were painting these intimate scenes — ”private human events” as David Palfrey wrote about them. There's still a good bit of repetition in your work, but it seems much more refined, pared down. Can you speak on the process of going from these “private human events” to these very isolated representations?

AP: Yeah, so that show is actually a really important show for me, and that review is important for me because first of all, it was my first art review out of graduate school.

NR: And this was the ‘Time Lapse’ exhibition, yes?

AP: Yeah, and it was my first solo exhibition after graduate school. I love that he mostly reviewed films. I was interested in building these paintings, thinking like a filmmaker would build them, which is why I call them storyboards. Because it's not a finished product, it's a thinking tool. And I love that idea that you're finding something like hand to paper in the same way that I want to find things when I'm drawing. I find the shapes, let the shapes reveal themselves to me. How do I want this scene? It's gonna be a close-up, and then it's gonna be a pullback, and then there's gonna be something from the side, and then I'm gonna look from the top. And I wanted to do that same thing where I wanted to see a single moment or a single activity from all sides. This probably goes back to my obsession with Picasso when I was a kid. [laughs] How can I see everything from multiple angles?

So then I got interested in what would happen if all that fell away? And I blew a single moment up. That as a making process was a real challenge, too, because I had to shift the way that I made something. It became, how can I zoom in on a single moment and strip that down and have that be an engaging experience without all the noise around that…

NR: Narrative or the setting or the before and after to situate a single image.

Pivot 1, 2024. Powder-coated Aluminum, 20 x 20 x 30 inches, Cary Norton Photography

AP: Yes, exactly. And the repetition was not only the repetition of the activity that you were looking at, but the repetition of my act of making. That's the part that is still important to me. Like the show that just opened at the Bemis. I was just talking about how that piece came into being and again, it was all on little pieces of paper. Oh, they're out on the table, actually. And I was trying to draw something else and of course, it was an accident, which was lovely. Accidents are always lovely… and then I was like, “God, this is weird. I don't know what this is. I don't know that I like it. Do I like this?”

NR: I love that feeling in the studio.

AP: Me too, it’s the best. So then I put it away and then I kept looking at it. I was like, “There's something here. This is really weird and I like it.” And then I started drawing it again and again, and it became the shape I felt of this moment. And it's this female form that's coming up out of the earth and opening up, and it feels a little bit ominous. It also feels joyful. It's all of those things in this one image, and I felt like, “Oh, that's the one.” I had been working on all these different ideas leading up to it, trying to figure out what was going to be right for the space. And I was like, “This is the one. This is the shape for that project.” So it's in the repetition of drawing something again and again, my understanding of it by doing that. Also allowing — what a lot of people don't get to see in the background — are the tiny shifts in the shape and the tiny changes to how it moves completely changes it. It becomes what it's supposed to be, and I wouldn't know it had I not drawn it 20 times.

NR: Yeah, it makes me think it's having a life of its own and it's not repeating exactly, even though the shapes are similar, the nuances are different.

AP: Yes, which is also why I like to show things in series often, because that's where I feel their power is. Seeing something moving and changing and coming into being. And that's a lot of the stuff that's in the background sometimes. For me, that's the beauty in artmaking – that you become a channel that something moves through. I know you probably have this experience too. As soon as you try to hold it too tight or to make it something that it doesn't want to be, it's ruined or it's not engaging or doesn't have that energy or that life in it. So when I can finally get to the point where it's let go a little bit, it emerges. It always emerges. It's the beauty.

NR: Now to shift gears a bit… because one thing that's always fascinated me about your work, which I was first introduced to in 2019 at your exhibition at Whitespace.

AP: 2019? You mean 2017? It had the banners?

NR: No, it was the one with ‘The Messenger’s Mouth Was Heavy.’

Unstoppable Sadness, 2024. Gouache on paper, 30 × 22.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist

AP: That book came out in 2019. The last solo show I did with Susan Bridges was 2017. And I did a three-person show with her, with Mike Goodlett and Donté K. Hayes in 2021… is that the one?

NR: Yeah, that must’ve been it!

AP: Yeah, the book was a fun project.

NR: It's something that's captivated my mind for a couple years now. Can you talk to me more about that typeface that you developed with…

AP: With Michael Aberman, amazing designer.

NR: From a typographical point of view… it's so unique, and I'd love to hear more about that process.

AP: Talking about the way that I draw and find my shapes, I've always thought about handwriting, especially because… I've terrible handwriting, by the way [laughs]. Thinking about the brush and the ink and writing and marking and trying to have that process, almost a stream of consciousness process or how you think about writing the letter. You're drawing across a page and you're writing as the words are coming to you, and thinking about drawing like that. That's how I started the storyboards, and it was letting things form in the moment.

Writing and forms of writing have always been interesting to me. Michael was part of a curatorial collective that did a show in Chattanooga at the Chattanooga Choo Choo in a train car — hilarious. So I was in that, and that's how I met him. Later, he wrote me and was like, “Hey, I've been thinking about your work and I think it would be interesting to do a book. What do you think?” And I was like, “Oh, I would love to do a book.” Because also I did a couple of earlier projects where I worked on accordion-folded paper. I wanted them to feel like books that had come apart. I was drawing on the front side and on the back sides of the paper so they were, again, gridded where I would draw square to square and it would be like a story unfolded, but it was images and not words.

There were all these connections to writing and reading and text, but I never thought about taking it into this place. When we started talking about designing this book together, he was so generous and so thoughtful, too. He was like, “I don't want to take the liberties with your work that you're not comfortable with.” And I didn't mind because we both were not interested in doing a straightforward monograph where it was a picture of a work with the text below, that kind of thing. We wanted the book to be a work of art. So we just started this year-long correspondence where I would send him images and he would play with the images, not altering them, but playing with the layout of the book, scaling things up, because scaling is something that is… I love scaling. I think about scale all the time and it's something that's exciting to me and how it changes the way that you experience an image. How your body experiences work depending on the scale.

So he started blowing things up or shrinking things down or making relationships between images that I wouldn't have, which was a fun discovery for me. He wanted to… with my works on paper, I mostly stain the papers too, with colored inks, to build these grounds up that I then draw on top of. So he was matching certain page colors to that. And then he said, “Would you mind if I created a typeface with your drawings?” I was like, “This sounds like the most exciting thing.” So he created an entire typeface that was uppercase, lowercase, numbers, punctuation, and every single one was a drawing I had made. I can type that out on my computer. It's so cool. So then for my drawing to become a language that could then be read and an actual alphabet has been really fun. And something that I'm thinking about also how I can take into other places as well with the work. So stay tuned, but I’m not sure what yet. But there are things that are brewing.

NR: Yeah, since you made this typeface, how has that maybe in turn influenced the work that you make after it?

AP: Right, and I think it has. There's works that I've made, for example, like this painting right here. You asked how sculpture then influences painting and drawing afterwards, because I was taking the drawing into sculpture. But now the sculpture is making its way back into painting and drawing in a weird way, which is so cool, because this, to me, feels like a sculpture, like the hand, the other figure that was from the art fair. I love how it can disappear, depending on where you're standing. And then appear. Because it's cut out of this tiny, thin aluminum, it's not all there and also they're always folded. That came out of the folded drawings that I was just talking about. And then I started making these folded sculptures in my studio, which were where I realized the quickest way to go from drawing to sculpture is to fold this paper in half and stand it up.

Split (Seated), 2024, ink and gouache on paper, 22.5 x 30 inches. Courtesy of the artist

I always play with collage. It's a way of thinking. So it became all these things merged together and then with the fold, you had that play of part of it totally disappears and you're looking at a completely flat, two-dimensional shape, but then it becomes something else as you move around it. And so this painting [Split (Seated), 2024] was thinking about this sculptural form where you're standing in one point where a lot of the body disappears into a line. So yeah, they're definitely all weaving together right now.

NR: Thank you for that explanation because I've been looking at some of these series, like this is part of ‘Split (Seated)’, I think. And now it's clicking for me, how these sculptural elements have influenced these two-dimensional works. And before we get too far away from writing… There's something quite poetic about your work. I'm interested in how you figure that poetic element into it, if that's intentional, in particular ‘Unstoppable Sadness’. It almost looks like a letter or text written out, and you can even read “unstoppable sadness” at the top. And there's an ellipse at the bottom, how are you thinking about writing these things out?

AP: Right, then it becomes its own thing. That's what I was saying. It has been so cool because the drawings then became this text, and now I'm actually drawing the text as an alphabet. The intensity of the time that we're living in right now, is why I made that Unstoppable Sadness drawing. It just feels… it's just a difficult time. I love that the text can be difficult to read too, and that urge to read something and know what it is and know what it means. That's why I made that drawing. Like I said, I'm interested in how I'm going to take some of that forward.

NR: Yeah, I look forward to seeing how that manifests.

AP: I feel like you had another part to that question that I didn't answer.

NR: Oh, I'm always interested in the poetics of something or poetry in general.

AP: Oh right, right. Yeah, it's not intentional. I love that you read the work as being poetic. It's that beautiful thing that takes you from something ordinary into something that you feel is outside of yourself, which, for me thinking about poetry, which I was never a big poetry reader, but Pete, my partner is, is very much a poetry reader and lover and brought that into my life. Just thinking about how you rearrange words makes you completely engage with it in a totally different way.

But I've thought a lot about that too. It's something that's unpredictable. Is what I was trying to get at. I always think about jazz. Jazz is not necessarily predictable, so it makes you a more active listener. Poetry is not a predictable pattern of language, so it makes you experience something that you're reading in a totally different way.

NR: It feels like something that connects you with a greater sense of humanity?

AP: Oh my gosh it does.

NR: You talked earlier about scale, and I would love to hear about how you approach and think about scale. With your work taking different forms across mediums, they also shift in scale. How does this affect your approach with pieces such as Surface at Bemis or Arrangement at the BMA?

AP: I draw so small, and that is how I find my shapes, and all of my work is within this gesture of my hand with a brush. Then what is that experience of seeing that work on that scale? Cause most people don't see those, they see the paintings. I wanted to have a body-sized canvas. I wanted to feel my body in relationship with the painting. So taking those shapes larger is not necessarily that easy and you want it to have the same hand. I want it to feel it has the same gesture in making the little drawings that I'm making or these single gesture forms. So when they're taken larger, it's important that my hand still be there.

A lot of people want to know if I use tape or something, and I don't use tape to make edges because I don't want them to be perfectly straight. I want my hand to be there. That's part of that humanity that I look for in work that I want to be evident in my work. So I want all of those things to feel found still. I love the little drawings, and people don't get to see the little drawings because they're all in my flat files. But I started showing them every now and again where I would frame some of the little drawings alongside a solo show I was having, because those are where it all comes out of. To me, they're precious; maybe they aren't precious to everybody else, but because we usually dismiss things that are small scale. What I like is there to be that surprise of seeing the tiny nuances in those small drawings and, for people to get to see how they're made, that they aren't… you brought up in your first question, it was important to me that things aren't outlined and filled in, because I think that's where, for me, drawing gets lost. It has to move and emerge. When I go larger, though, and of course, with painting, you're having to construct them in just a different way.

Folding I, 2023. Oil on canvas, 72 x 108 inches

NR: Right, it's harder to make broad gestural strokes on such a large scale.

AP: I am not an abstract expressionist painter. So how do I take this up in scale and still try to retain the hand? That's probably one of my biggest challenges. And for the sculpture, though, the clay, I love clay and I love how the clay holds the hand. I love how the clay is not perfect. I love how the clay bends in the kiln, all those things I love. But for me to go up in scale and make some of the shapes that I want to make, it was then transitioning into aluminum where I did the next round of sculptures. So then where's the hand? The hand is in the drawing. The drawing is getting translated. So that's where it is because the material doesn't have the hand. So the shape, I hope, can hold the hand.

NR: So you almost see these aluminum sculptures more so as drawings than your clay sculptures, which are forms where the tactile nature of ceramics is harder to separate from the hand.

AP: Yeah, you can’t.

NR: Going from medium to medium, was it ever fluid, or was it “Oh, how am I gonna do this?”

AP: It actually…. well both [laughs]. I was about to say fluid, but no, because it was also hard. I think the first time I wanted to get into clay was the first show I did with Susan Bridges at Whitespace. Leading up to that show, I'd been thinking about how I wanted to make these raw… head… bust sculptures. I just decided to go for it, and I didn't want them to be fired. I wanted them to be sculptures that would deteriorate afterwards, and it wasn't about longevity. So I started making those sculptures, and that's where I came to my first folded sculpture. I was making a series of heads and then I made the first one that stood on a 90-degree angle, and I was like, “Oh, there it is. Okay, that's where I want to go.” So yes, you had the awkwardness and the weirdness of me going “Okay, I'm making clay sculptures, what are these?”

And they were, because I was relating them to rocks again, out on the lake bed my grandparents lived on when I was a kid. It was a TVA lake, so there was a dam and they would let the water out in the winter. When we would go up for Christmas and Thanksgiving, we would go out and play on the lake bed, and all these rocks were emerging out that looked like parts of sculptures or bodies or heads, and I thought, I want to try to recreate that same thing, these things that look like rocks, but they take on a figurative shape. That's when I came to the first folded sculpture, and then after that, I started rolling slabs and cutting them out and trying to think about the sculpture as drawing.

Collapse IX, 2024

Even in the clay, I was thinking about them as drawing because I wanted them in the same way that I drew with ink and a brush in this fluid way. I wanted to go in there with an idea, and cut the shapes out with a knife and put them together. Usually in a folded shape or with a flat front and a flat piece on the back and then stand them up and paint on them. So there was a second element of the drawing on that. So, yeah, I feel like all of it has come fluidly in the sense that early on, I was making those paper sculptures but I had no idea that I was going to take those into any other material or scale.

NR: Yeah, when I look at your work sometimes I wonder, “Is there anything that she can't do with these forms?” and it's pretty amazing…

AP: You asked about the Bemis Center, the scale of those. I thought for all the reasons why I felt that shape was so powerful at the time, especially, when I decided to do them there, I realized with the scale of the room and I laid it all out that they were going to be like 12 feet tall and nine feet wide. It was so exciting because I felt that shape was so powerful that having them on that scale would be even more powerful. So as you approach them in the space, they became like these… I don't know.

NR: It's almost like a temple or something. At least from the pictures that I've seen online, I haven't been able to make it up there, but it feels very…

AP: That’s how I wanted them to feel.

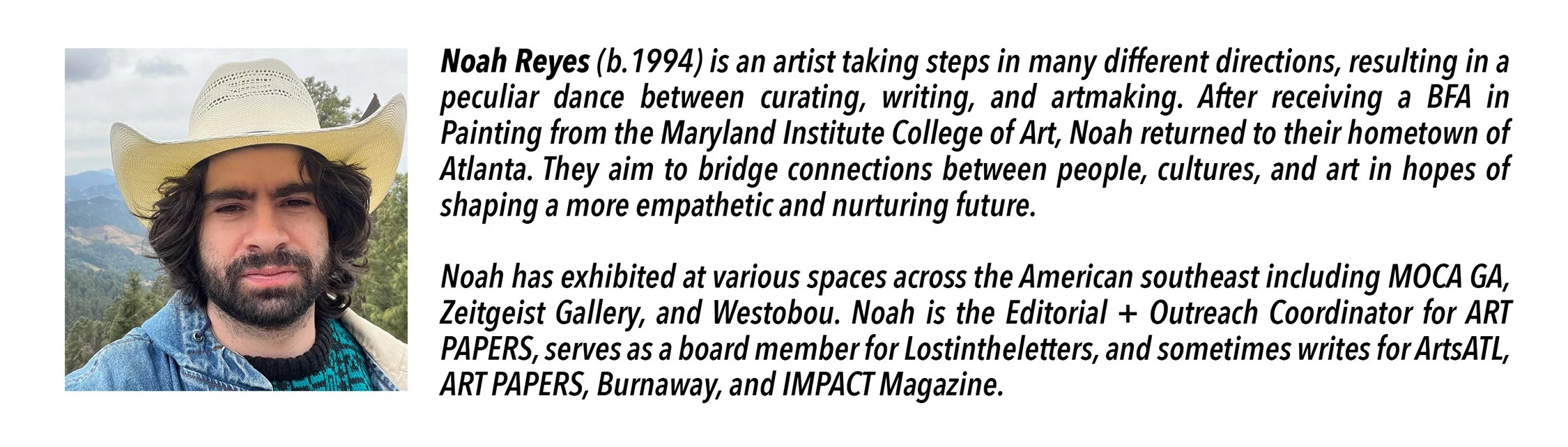

NR: Well, I think you hit the nail on the head right there. You mentioned earlier having an interest in Picasso as a child, and I've read that you come from an artistic background. With members of your family being artists, it sounds like you've always been surrounded by the arts. How did you maintain perspective on choosing to pursue art as a career?

AP: It's funny. That's a great question because I never even thought about that. I was always like, “Oh, I want to be an artist. I want to go to art school.” I don't know if it was because it was 1990 and maybe things have changed now. But I guess I didn't even think about a career. I just thought, “Oh, I'm going to be an artist and I'm gonna make work” and I didn’t think about, “Okay, how's this gonna work?” Nobody talked about professional practice when I went to art school, you didn't talk about that. You went there, you made work, you had your work critiqued, and then you went out in the world. I feel in a lot of ways I was clueless about that and didn't even think about… I knew I wanted to go to graduate school. That was something I knew I wanted to do, but I didn't want to go right away.

When I got out of the [School of the] Art Institute [of Chicago], I was like, “I want to take some time off. I want to see what will happen when I am alone in a studio. What's my work going to be?” So I took three years off and then I went to Tyler [School of Art and Architecture]. When I got to Tyler, that's when I worked with Stanley Whitney and Margo Margolis and Dona Nelson. Amazing artists. And I got my butt kicked and it was great, and it was really hard, but it was exactly what I needed. Had I not had that experience, I'm not sure how long it would have taken me to get to my work. It was at that point where you have to find what's yours in your work. What is the thing that is uniquely yours? And so often you don't even know. You have no idea. You can't even see what's in front of you. It takes people from the outside to be like, “This is interesting… This is not,” and that it was the drawing. That's where I was who I am and what my work was and where my interests were. I had to figure out how to get that into painting and elsewhere.

As far as career went, I had no idea how to find galleries or find people. You're taught then “we have slides.” We had our little slide sheets, had my little labels and you made packets and you wrote letters and you put them in those yellow envelopes and then you mailed them out to people and you waited. We had no cell phones in grad school and with none of that, there was no social media. So I started working at a local art studio out of school. Working with high-risk youth and autistic adults and trying to make art when I could on the side, and then I went to grad school. And then when I got out, I was like, “I can't live in Birmingham, Alabama, and have a career as an artist. There's no way anybody's gonna take me seriously. I'm gonna become invisible,” all those things. Plus, I had children after that. So I was like, “This is going to be hard.”

Running in Circles II, 2023. Oil on canvas, 40 x 48 inches

My grandfather would have said, “You're not lucky. Luck is when hard work and opportunity meet.” That's what he used to say. So I made work, I was very dedicated, and Jeff Bailey, who was my dealer for 14 years, was coming to Birmingham to visit family and reached out to the curator of the museum and said, “Hey, is there anybody I need to visit in their studio while I'm in town?” and he said, “Hey, you should go to Amy Pleasant’s studio.” So he came and we had a great visit and he was like “Do you want to do a show?” and that was my first show in New York, 2004. I worked with him for 14 years and it was somebody that was like, “Wow, somebody is going to work with someone in Birmingham,” and it was a great relationship until he closed the gallery. But a fantastic dealer to work with. Then I learned, I learned everything through doing things wrong and meeting people, building community and it all has been an amazing process so far.

NR: There are a couple of things that you talked about there that I would like to pick out a bit. So you were teaching at-risk youth and… Well, I'm somebody that's interested in teaching one day, so how was that experience? Do you still teach?

AP: That was an amazing experience. It's a place called Studio by the Tracks. It was a great experience for me because I just started working in the group settings and doing all kinds of projects there. I worked worked four days a week and I always tried to have Fridays and weekends for my studio. It was a rewarding experience because it showed the power of making and people feeling free to express themselves in whatever way is needed through art. It was a powerful experience. I did that for a long time and then also at that time started teaching just independent classes because there were a few kids there that were talented and wanted to do something with it. And I felt that was something I could offer. The Alabama School of Fine Arts has the portfolio days. So kids have to have portfolios to get into the school. So I worked with three kids helping them prepare for that and that was incredibly rewarding. I did teach later at an elementary school for a little while, and for the last six or so years, I've been able to do this full-time, which has been incredible. Teaching is really important.

NR: I think oftentimes it can be a bit of a thankless job, unfortunately… But I would not be where I am today, sitting here with you if not for some of my teachers and I love the possibility that we can do that for other people.

AP: Absolutely.

NR: You mentioned this feeling of being from Birmingham and not being in New York. The art world talks about other places as art hubs, New York or LA, but I think there's something special about the south and being a creative person here. It's not always easy to explain. As an artist and curator, what do you find so special about the South and how would you describe it to somebody that's looking from afar?

AP: Right. Well, what I found and what Pete found, and he's from the Midwest, is that the community in the south is not limited to a single place, which is a beautiful thing. I feel we're all in community because we have so many good friends who are artists in Nashville, Atlanta, Chattanooga, and Knoxville… in New Orleans. It almost feels like it's one community. And I think it's because when you live outside a major arts center, you need to create community. People reach beyond, which is what happened for me, because when I moved back here, I didn't know anybody. I grew up here, but I didn't have any art friends. I didn't have an art community.

So I started driving to Atlanta. Atlanta's my second home. That's how I feel about it. Because I was like, “Okay, I need to go to openings. I want to meet people and I want to have conversations and do all that.” So I started driving over for openings and meeting people and making friends. I felt I became part of the community there, which was awesome. That's where in the south I started showing with my first gallery, there. The south is a very rich place and I think most places get stereotyped and generalized, and yes, it may be all those things, but there's also an incredible richness here.

Birmingham in particular is, a great city. And as any rebellious young person, they can't wait to get out of their hometown and never come back, and that's how I felt. But to be able to rediscover it again and feel a real part of the city has been rewarding.

NR: That's how I felt about coming back to Atlanta. I was born and raised there, and by the time I went to college, I felt the need to go see another part of the country. I didn't get too far, but ended up going to undergrad in Baltimore. I spent about four years there and when I came back it was like starting from nothing. It took me a couple of years to get my ground and find out the galleries that you go to and this and that. It's nice to hear you say that about the South, because it does feel like our community is… not exactly tight knit, but close or…

AP: It feels connected. The other thing I end up talking about a lot in terms of Birmingham, that one of the most important things for me and being able to sustain, was the affordability of Birmingham. There is no way I could have done what I did in that time period had I been living in New York or somewhere else. As difficult as it is to live outside a major city and stay visible. It was also incredibly important to find a stable way to have a sustained studio practice and be able to afford a quality of life that was important to me.

Arrangement, 2023, paint on walls, 54’ 7” x 10’ 9”, Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama

Photography by Cary Norton

NR: What are some things, arts organizations, galleries that you think people should know about in Birmingham?

AP: We have a lovely museum, the Birmingham Museum of Art. It has a pretty incredible collection, which I think is special for a small city. That's another positive and that was also something early on that made me feel like I can live here and be a part of a community because of the museum and we had a great curator. We've had several great curators, and we had Collectors Circle for Contemporary Art and an amazing group of people and collectors who I had no idea would live in Birmingham and actively travel, were actively engaged and have great work and are generous, wonderful people. That was a huge eye opener and they have been very supportive of me, which I am so appreciative of.

We have the Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, and John Fields is the director there and Hannah Spears is the curator. She's just moved here from LA and they do an amazing job and they also have a member's collector's group. They do great exhibitions and lectures and always bring an interesting artist every year to jury the student show and have an exhibition and do a lecture. Alex Chitty was just here, Amanda Ross-Ho.

We have more galleries than we've had in a while. Ground Floor Contemporary. Sarah Armstrong founded that. It's like a member's gallery, but it's one of the only places in Birmingham where there is a studio complex, where artists can have studios and have community space and feel they have a support system. The exhibition space, even though it's small, is lovely. They do great shows there. Scott Miller Projects is a gallery that hasn't been around for very long, maybe a couple of years now. It’s downtown on Morris Avenue, which is a historic street where we used to hang out as high schoolers and punk shows and the trains, cigarettes.

Another thing that is amazing that Birmingham has is the Sidewalk Film Festival. That is a very big deal and nationally recognized. They do an amazing job. We have a great music scene too. Bottletree was legendary… one of my closest friends growing up, Merrilee Challiss is an artist, an amazing human. We've known each other since first grade – both of us moved away to go to grad school in Philadelphia, and both of us moved back to Birmingham and decided to be a part of the experience here – she started the Bottletree, which was an incredible music venue that closed. And now we have several venues, one down the street, Saturn. A lot of great artists come through here, which is great because they used to always skip Birmingham. They go to Atlanta wherever they were going. Yeah, I know there's probably something else.

NR: Thank you for that. I appreciate it because I love the South, and want to make sure that people know how many wonderful institutions, organizations and galleries that we have here.

AP: I will also add, an amazing experience of which when I was a teenager, Lonnie Holley lived here. He's from Birmingham. His property was out by the airport and my dad took me out to meet him when I was a teenager and it was one of the greatest experiences because I remember when I was a kid, he loved kids and again back to teaching. He was called the Sandman and he loved working with students and showing them how to carve out of sandstone. I don't know how many of his sandstone sculptures you’ve seen because they're rarer to find now than his paintings and stuff.

Then David Moos did an amazing exhibition with him at the BMA after I got out of grad school. Lonnie would go and fill a dumpster up and then they would crane the dumpster into the outdoor sculpture garden and then Lonnie basically lived in the space during the day and made work and you could go and visit him and talk to him. He walked around, played music, made sculptures. It was this living breathing, art installation. It was incredible. And then, of course, there's Joe Minter’s African Village that's here. It's a very rich community.

NR: How about The Fuel and Lumber Company and how that experience has been. How did that start?

AP: It started after I met Pete. He had done some curating before, when he was in Iowa City after finishing graduate school. We wanted to try to contribute in some way to our community. Our first exhibition was Jiha Moon, in 2014. We did a solo show with her and she's one of the first people that I became friends with when I was coming to Atlanta and going to openings. He [Pete] lived in Tuscaloosa teaching at the University of Alabama. So we turned one of the rooms in his house into a gallery, with track lighting, we painted, and turned it into a gallery and Jiha Moon was there. Jay Davis, William Downs, Lisa Iglesias. Those were all solo projects. Oh, Jane Cassidy. And then he [Pete] moved to Birmingham and we started using my downtown studio a couple of times but you can't give up your studio for exhibitions. It was like, “Yeah, I'm not gonna be able to do this often.”

NR: Maybe for one night or a pop up, occasionally.

AP: Exactly but yes, the whole point, we both were of the same mind, we never wanted to have a physical space because neither one of us had the time or the energy to run a gallery.

Collapse X, 2024

NR: It’s a lot of upkeep.

AP: It's huge. We also never wanted to be money changers. So if anybody was interested in buying something, we just connected the person to the artist because as soon as something becomes about money, it becomes a whole other animal. We just wanted to be facilitators and our last show was the Pasaquan show, half at Pasaquan and half at the Bo Bartlett Center. That was an incredible experience. So we took a pause after that because that was a huge show. We were also coming off this high of these amazing generous artists who — it's amazing to see how artists love to be a part of exhibitions that are outside the box, outside of the gallery space, and find it a challenge and inspiring. So we've had such amazing interactions with artists. It's a rewarding thing. It's so much work as you know. But it is so rewarding and exciting. So we're working on a couple of things that are upcoming, which is cool. But we never wanted it to be too demanding because we're both practicing artists and Pete also teaches at UA, and so it had to be what felt right and it had to be the right timing.

Also, we always love shows that artists curate way more. It's a different thing, artist-curated shows are so rich and come at things from a different perspective. I don't know if you saw Amy Sillman’s exhibition she did at MoMA where she got to pull from the whole collection. It's called The Shape of Shape. She was pulling everything out of the collection, making the most interesting relationships between works.

NR: I will look into that, thank you. The flip side to that, with artist curated shows, how do you feel your involvement with Fuel and Lumber has impacted your approach to your own shows?

AP: Yeah, our favorite part of curating is when you get all the work in the space and you start to see how things talk to each other and it gets so exciting. What you think was going to go in one spot or with something else you're like, “Oh my God, but look at it with this. Oh, if this happens,” and it is so thrilling that I think both of us curate our own exhibitions in that way, where I can't have it all figured out because as soon as you move a work out of the studio and into another place, everything changes. It's just letting things be what they are and see what it tells you about where it wants to be or who it wants to talk to. [laughs]

NR: How you find a balance between these two endeavors, between curating and making art as well as just living and existing as a human being?

AP: I know, it's a lot. I remember I was talking to an artist friend who also had kids and curated a space and had a very disciplined studio practice and was also the curator of a university gallery. I said to him “God, how do you do all that?” And he goes, “Let's not talk about it because I can't, you know, because you just do it.” As soon as you start to figure out, how do I do all these things? It’s just like [laughs]... what Pete always says is, “Don't look it in the eye.”

Young artists will ask me a lot, if a student group comes by my studio or something, they'll say, “Well, what's it like being a mom and an artist?” and I always say, “You just figure you find a way.” If you want to have kids and you want to be an artist, you can do it. You just have to figure it out. You have to figure out how to schedule your time and you just do it. And so for us, like I said, we don't over schedule. That's something I think you learn with age too is now, I’m 52 and you recognize what you're capable of or if you overcommit the level of stress and, you have to learn how to say no sometimes and find balance. I think that's the hardest thing, because there's never enough time for your work. I remember Stanley Whitney actually saying this to me in graduate school. We were talking about that very thing, how there's never enough time. And he said, “Even if you had your whole life to paint, it still wouldn't be enough.” And it's true, because there's always more, there's always more to make. There's always going to be more that you want to do and there's only so much time in a day. There's so many unknowns that come out of the corners, so you just have to stay focused.

Amy is keeping busy this year, see her work at:

Stove Works in Chattanooga this summer, and her solo exhibition at Whitespace Gallery, in Atlanta opens August 30.

###