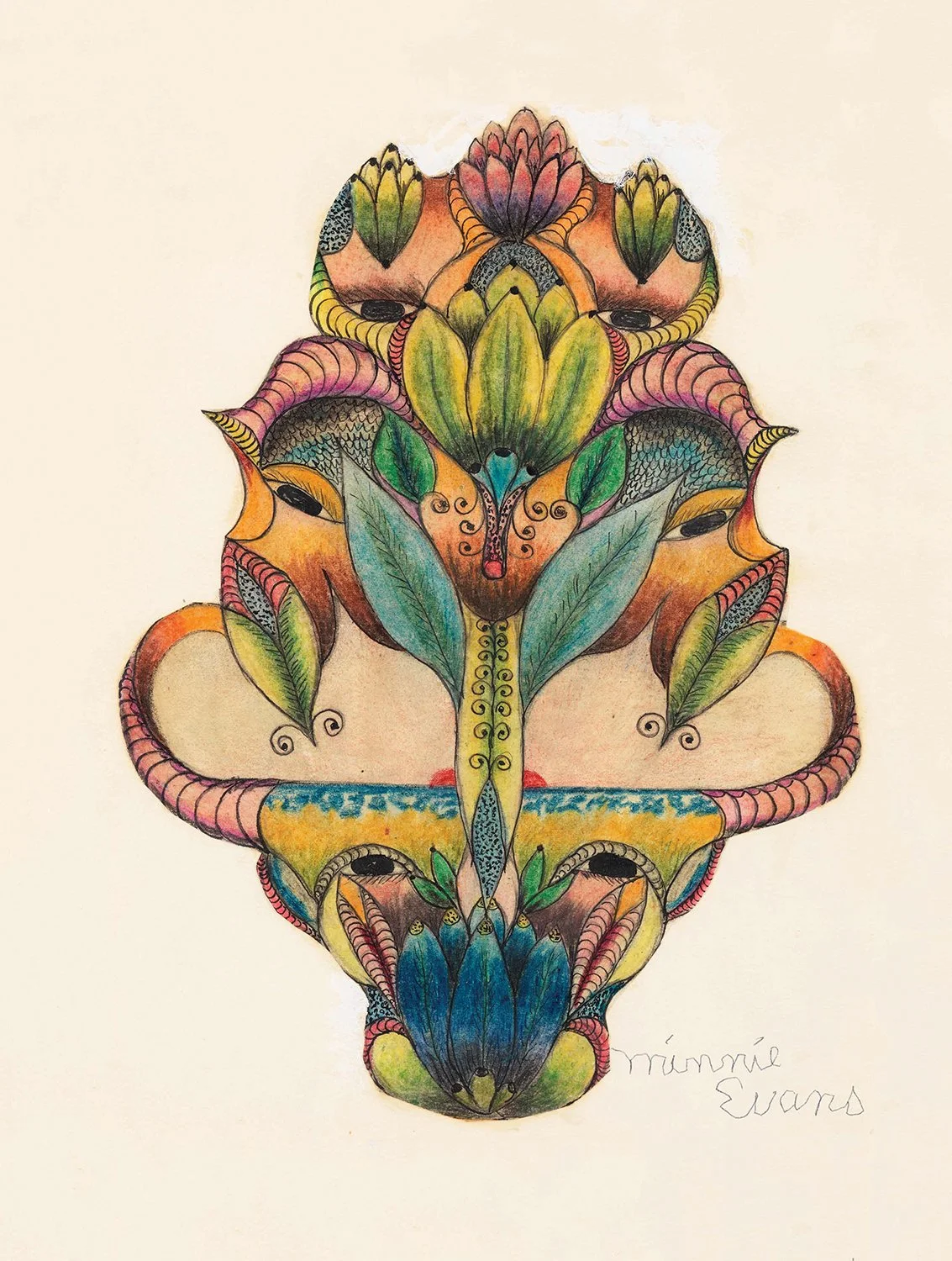

Untitled (Bull's Head with Sunset and Eyes Collage) ca. 1960. Crayon, ink, pencil and collage on paper. Collection Wendy Williams, New York, Photo by Christopher Burke

Minnie Evans (1892 – 1987) said her drawings of harmoniously intertwined human, botanical, and animal forms came from visions of “the lost world” or nations destroyed by the Great Flood described in the Book of Genesis. After her grandmother Mary died in 1934 and the visions she had been experiencing since childhood became stronger, Evans produced a large body of work, mostly on paper, in a range of abstract and representational styles. Primarily using wax crayons and pencil, Evans experimented with compositions whose complex symmetry resonates with the tradition of Hindu and Buddhist mandalas, known for offering representations of the interconnectedness of the universe. This association was never articulated by Evans, but it has become one of the most enduring of the many cross-cultural and transhistorical comparisons drawn by her art.

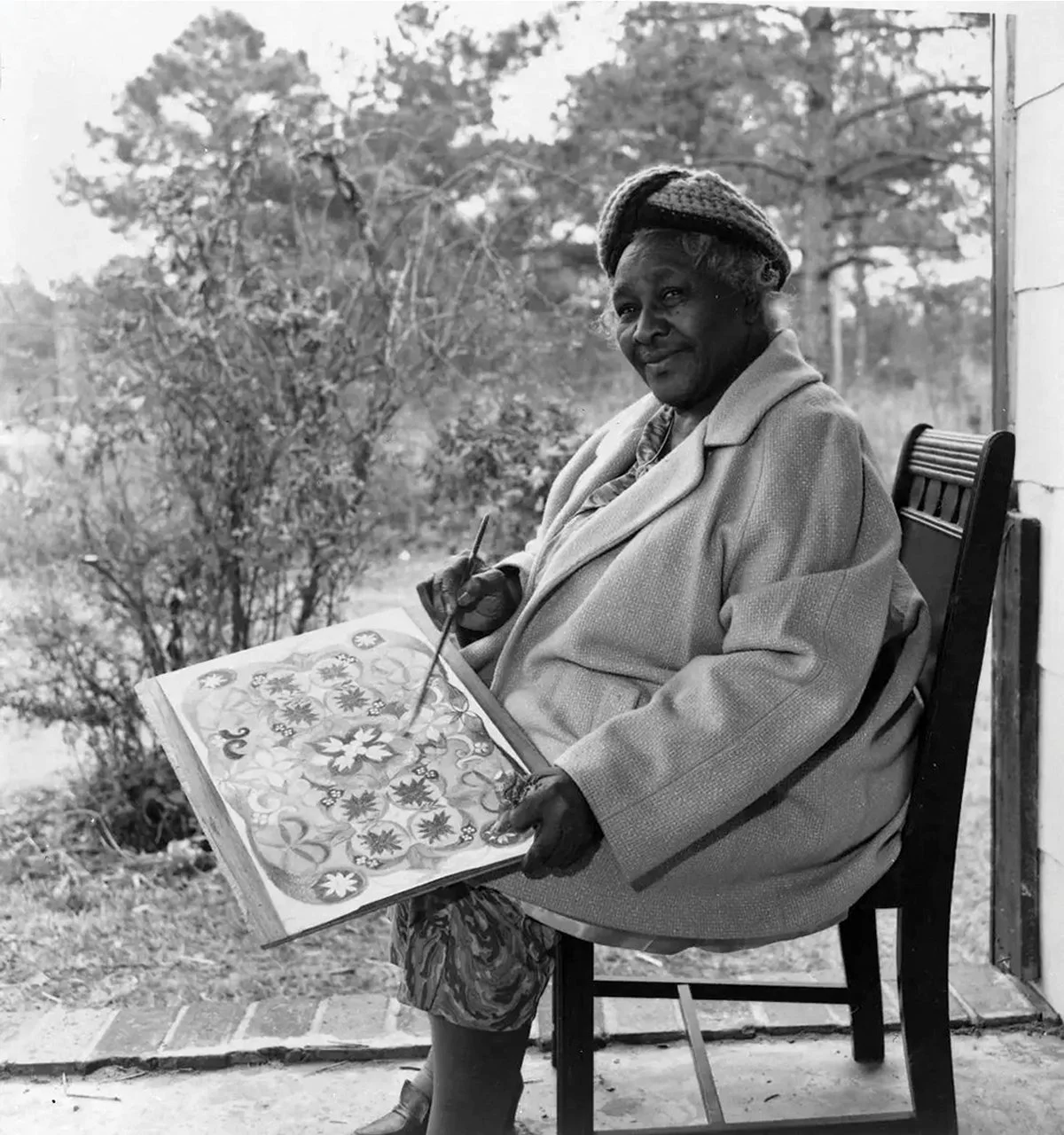

As an infant, Evans was brought to live in the coastal city of Wilmington, North Carolina, and called it home for the rest of her life. When she turned fifty-six, she shifted from decades of employment as a domestic worker to collecting admissions at Airlie Gardens — a destination for plant enthusiasts especially famous for its thousands of azalea specimens and stunning old growth oaks, still welcoming visitors today. Posted on the edge of one of the most beautifully landscaped gardens of the Southeastern United States, Evans made art during idle moments and hung it on and near the gardens’ exquisite wrought iron entrance gate, which bears a striking resemblance to the curvilinear twining that became characteristic of her drawings. In this way, she was able to sell or give her drawings to Airlie’s visitors, leading to a reputation beyond Wilmington and eventually a 1966 exhibition at a New York church organized by the photographer Nina Howell Starr, who had quickly become Evans’ most ardent supporter after befriending her a few years earlier.

Minnie Evans in Gaithouse at Airlie Gardens. Courtesy of the Estate of Nina Howell Starr

Although Evans experienced fame in Wilmington and beyond in her lifetime — including becoming one of the first Black women artists to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1975 — she has not been the subject of a major show since the 1990s. This November, the High Museum of Art will open an exhibition that reprises the title of her 1966 debut — The Lost World — not only out of deference to Evans’ interest in biblical texts and ancient civilizations, but also because our project foregrounds the spiritual and historical circumstances that shaped her day-to-day world. More than 100 drawings, as well as about a dozen of her rare paintings, will be presented in a roughly chronological order that unfurls her artistic development and offers a range of contexts for interpreting her art – from the extrasensory experiences of her visions to the double-edged realities of the extravagant estate where she labored in the Jim Crow South.

The High’s exhibition will also be accompanied by a catalogue, the first book to document Evans’s extraordinary artistic production through more than 100 color plates. And in 2026, the exhibition travels to the Whitney, marking an important full-circle moment for the artist. As the curator behind these projects, I hope to relay in this essay some of their major themes, while also exploring intersections between Evans and Surrealism, Swiss psychiatry, and Alice Walker that didn’t quite make the cut of my final word counts. There is always more to say, it seems, and indeed my hope for our reincarnation of The Lost World is to plant seeds so that greater knowledge and perspectives on Evans can continue to flourish in the future.

First, a few notes on the motivation behind The Lost World 2.0: The number of deserving self-taught artists who merit serious exhibitions is overwhelming, but Minnie Evans rose to the top of my list for several reasons. In addition to her increased presence in the High’s collection thanks to major gifts from Chuck and Harvie Abney, Carl and Babe Mullis, and Jane and Barbara Kallir in recent years, the past decade has seen a spate of new essays, articles, and a master’s thesis on Evans — vital new scholarship that inspired many of the new directions of this project. Her art has also been popping up in larger modern and contemporary art exhibitions, especially those reappraising legacies of Surrealism through feminist and Afro-Diasporic lenses. This new dimension of her belonging continues in this exhibition’s catalogue thanks to an insightful essay by curator María Elena Ortiz about how Caribbean thinkers like Suzanne Césaire and Édouard Glissant can illuminate the art of Evans, who traced her ancestry to a matriarch who was enslaved and trafficked to Charleston, South Carolina from Trinidad.

My Very First, 1935. Pen and ink on paper, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, gift of Dorothea M. and Isadore Silverman

Evans’ intersection with Surrealism has actually been part of her reception since the 1966 Lost World exhibition. She has been called an “innocent” and “unconscious” Surrealist, both modifiers gesturing toward the fact that she had no professed knowledge of the artists who convened in Europe around the writings of André Breton or in the Caribbean around Césaire, despite coming to many of the same conclusions herself. Evans, for instance, heeded the content of her dreams, which came with frequency and lucidity: “I haven't ever slept in my life without dreams,” she said. “My whole life has been dreams." In addition to channeling imagery from her dreams into her art — from a nightmare-inducing cemetery hiding to lions that carried her in a parade down Fifth Avenue — Evans adopted other modes of working that mirrored Surrealist practices. Her first drawing, for instance, emerged through the kind of free flowing mark-making that the Surrealists called automatism. In one of her descriptions of making this tiny but powerful drawing, which is now in the collection of the Whitney, Evans remembered: “I had wrote my grocery order and after I tore that off then I had taken my pencil and went to making some funny things. I don’t know why but I just kept on making a lot of funny things . . .”

Nina Howell Starr, the photographer who facilitated the artist’s exhibitions in New York and other major cities during her lifetime, was herself steeped in Surrealist practices, having studied with Jerry Uelsmann, who was known for creating uncanny photographs through practices like multiple exposure. Preparing for a lecture she would give about Evans’ work in 1970 at the St. John’s Museum of Art — today the Cameron Art Museum, which hosts a study center dedicated to Minnie Evans — Starr noted as points of intersection between Evans and Surrealists not only automatism and dreams as sources, but also biomorphic forms and a playfulness toward orientation. This latter impulse is seen in pictures that Evans called her “turnaround pictures” because they could be hung from a variety of angles to more or less the same effect. Her emphasis on symmetry in these and other works, as well as her sense of her art as emerging through a divine channel, almost led Starr to call her 1966 exhibition Fearful Symmetry, after a line from William Blake’s “The Tiger”: “What immortal hand or eye, Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”

Blake was, like Evans, an artist who heeded dreams and connection to the divine as a primary catalyst for his art. Although she has been compared to him many times, Evans never noted Blake nor any Surrealist artists (some of whom counted Blake as a forefather) as influences. She was keen to talk about other transformative encounters, such as one with a fortuneteller in 1944 that led to her creation of Invasion Picture, a rare oil painting that she believed foretold the invasion of Normandy. Evans also frequently cited Drums of Fu Manchu, a film she saw in theatres about a Chinese supervillain who instigates anticolonial insurrection across Asia, as impactful. In this film, Fu Manchu weaponizes a tablet inscribed with fictive characters that reminded Evans of the glyphs she made in her drawings. She once brought her drawings to the theater and shared them with other filmgoers, saying, “whoever made that movie is cooperating with my pictures.” All to say, Evans did speak about sources for and affirmations of her art without ever mentioning Surrealism.

A Dream, Prophets in the Air, December 1959. Painting, North Carolina Museum of History. Photo courtesy of North Carolina Museum of History

Nonetheless, I would not characterize the striking parallels between Evans and her Surrealist contemporaries as “accidental modernism" — a kind of shrug-emoji explanation that has refused to die in discourse around self-taught artists for the past century.

For one thing, such parallels have occurred too many times throughout the past century to chalk them up as mere accidents. See William Edmondson and direct carving; Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses or John Kane and American Scene painting; Gees Bend quilters and alternative languages of abstraction; Thornton Dial and the “Combine,” to name a few. Especially when the timing of the lives of artists who get the credit for these breakthroughs and those that typically don’t are coincident — and this is certainly the case with Evans who was born within years of Breton and Max Ernst — we can seek explanation in their shared experiences of major social, political, and cultural change. In other words, conditions of modernity can lead to modernist breakthroughs regardless of where an artist sits on spectrums of training or cultural knowledge. Evans too came of age at the turn of the century, going on to experience two World Wars, widespread economic depression, and additional traumas from being Black in the post-Reconstruction era South. Retreat into dreams, the quest for wisdom from ancient civilizations, the imagining of worlds more harmonious than the one at hand, were all responses that Evans also embraced in her parallel Surrealism. She didn’t identify these gestures and methods as intentionally anti-rationalist, but did she need to?

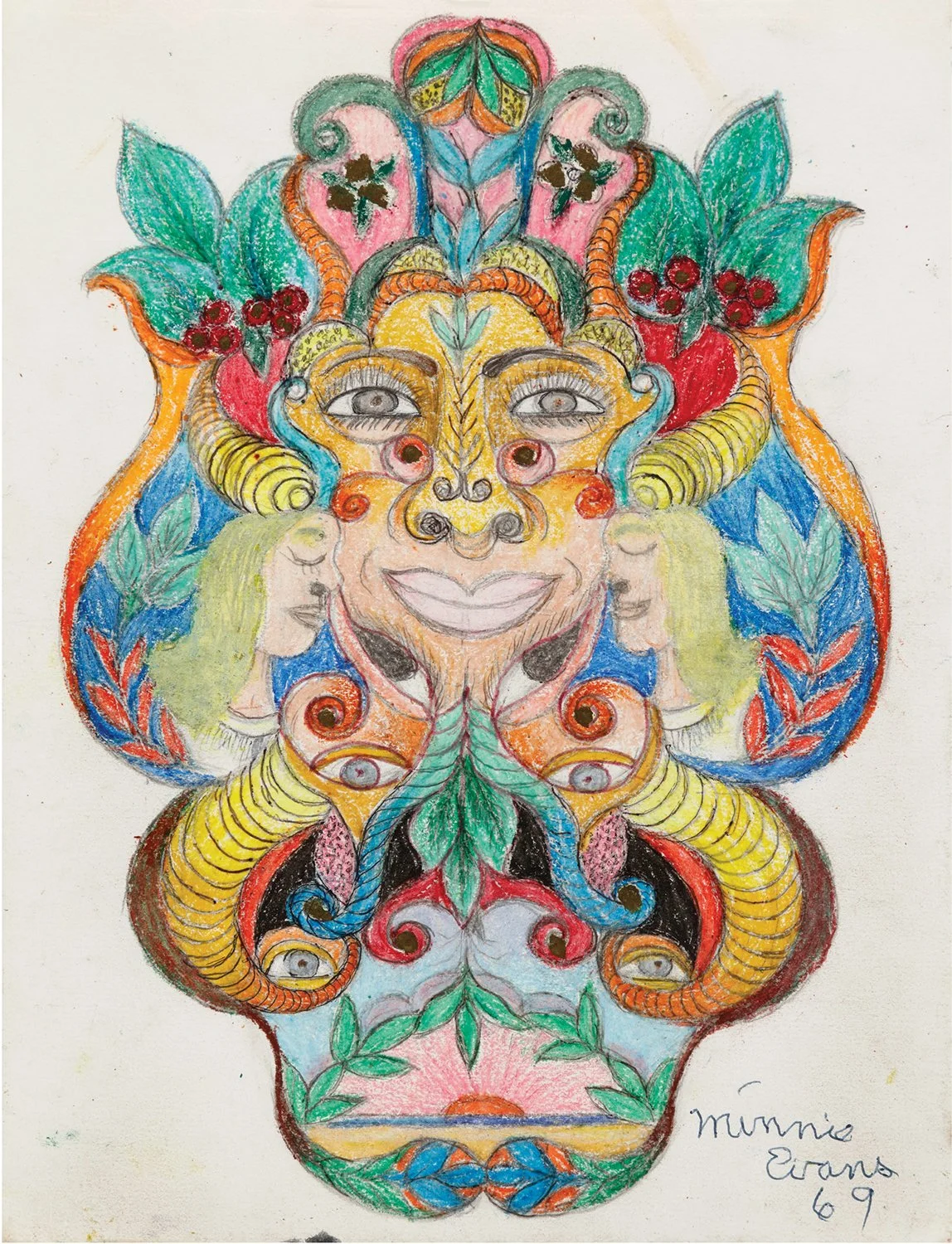

Untitled (Three Faces Surmounting Landscape), 1969. Crayon and pencil on paper, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, T. Marshall Hahn Collection. © Family of Minnie Evans

Evans was understandably guarded when speaking about race, but she spoke repeatedly about nightmares she had of ending up in a cemetery that likely reflected her experience of the Wilmington Massacre: “I started having those terrible dreams. Old men dressed up like the old prophets, they would carry me down to soldier’s cemetery. I have woke up more times in that cemetery.” On November 10, 1898, when Evans was six years old, a white supremacist lynch mob marched through the streets of Wilmington, blocks away from her home, with rifles and a wagon equipped with machine guns murdering as many as 200 people — the number is still unconfirmed. Many Black citizens too frightened to stay in their homes sheltered in nearby forests or in tree-canopied cemeteries around the city. Evans didn’t reveal much about 1898, only saying of the white people who perpetrated it, “they gets that way sometimes.” But her life was greatly affected by the massacre — one of her cousins was shot and left in the street overnight; he survived and relocated, as did her great-grandmother Rachael, who left for New York and whom Evans never saw again. To learn more about this all-too-relevant chapter of white supremacist power overthrowing electoral outcomes and becoming murderous in the process, see American Coup: Wilmington 1898, streaming on PBS (while PBS still exists).

In the exhibition and catalogue for our 2025 Evans show, I explore how in addition to a specific work she made based on her cemetery nightmare, many of Evans’ mandalas alchemized the dualities of beauty and ugliness, beneficence and evil, which she experienced throughout her life in the Jim Crow South. The intense psychological nature of Evans’ art was another Surrealist adjacent dimension of its initial reception in a variety of ways. On a formal level, the semi-abstract, vertically reflected structures of many of her mandalas resonated with the visual tests developed by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in the 1920s as a way to extrapolate and assess how people respond to ambiguous stimuli. As Nina Howell Starr developed a network of collectors and gallerists interested in Evans’ work, she came into contact with Charleston, South Carolina-based psychiatrist Robert S. McCully who would go on to reproduce one of Evans’ works in his 1971 book, Rorshach Theory and Symbolism: A Jungian Approach to Clinical Materials. As his subtitle indicates, McCully was one of the many American psychiatrists of his generation who studied and applied the writings of another Swiss psychiatrist, Carl Gustav Jung. A younger peer to Sigmund Freud, Jung also pioneered the study of the unconscious and was particularly interested in patterns he traced in dreams, mythology, and literature of peoples all over the world, leading him to identify universal “archetypes” that reappear across cultures and throughout history.

King, 1962. Colored pencil on paper, North Carolina Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. D. H. McCollough and the North Carolina State Art Society, Bequest of Robert F. Phifer

If Evans’ 1966 Lost World exhibition had a subtitle it could have been “A Jungian Approach to Minnie Evans,” given how prevalent the psychiatrist’s ideas became in framing her art at that time. The Lost World press release stated, “Anyone familiar with the work and thought of C.G. Jung will understand how strongly Mrs. Evans’ pictures interest his followers. That the source of her imagery lies in the collective unconscious is not only apparent visually, but her own words testify clearly and prophetically to this actuality." One of the Jungian archetypes that Evans’ work displays clearly is the ubiquity of a light source. A reverend named John Fletcher, who gave a sermon on her work when The Lost World was revived at a second church later in 1966, reflected on this: “Again and again we come back to the basic symbol, light, which is central to the creation myths. This light, the symbol of consciousness and illumination, is the prime object of the cosmogonies of all people." Celestial bodies abound in her drawings — evoking her reverence for the roles the moon, sun, and stars played in her life. She once reflected, “I would love to watch the moon and stars,” and the area of coastal North Carolina where she lived is a daily stage for magnificent sunrises and sunsets over the Atlantic Ocean — golden hours that appear frequently as pendants within her mandalas. Her engagement with light also reflected her accounts of her visions, which occurred during both sleeping and waking hours, sometimes disorienting her sense of time. During one episode that seemed to begin in the morning but included the darkening sky, she exclaimed, “What is this, is this the sun eclipse?” She recalled opening her eyes another morning as a “beautiful light appeared in my room... And there was a great wreath.” She also described passing out, regaining consciousness, and walking to her front porch, where “everything I looked at was rainbow.” Her colorful, radiating mandalas, so often lit from within by a celestial body, thus embody the aesthetic experiences of her visions.

Our 2025 Lost World presentation upholds the significance of Evans’ visions, chronicling her accounts of them throughout the exhibition didactics and the catalogue, and encouraging viewers to see how the aesthetics of her extrasensory experiences shaped her art. But it also rejects the idea that she or any visionary artist is an empty vessel filled only when divine inspiration flows. To the contrary, they are shaped and molded by many other experiences and exposures that the rhetorical power of the divine all too often drowns out. As Sharon Patton beautifully articulated in various essays about or including Minnie Evans, visions were a useful framework through which Evans and other artists were able to justify their creativity, both to themselves and others. Patton writes:

“Furthermore, imagine an artist approximately age sixty who does not belong to an artistic family and lives in a community where art has no exchange value or which does not see art as an important part of daily experience yet is suddenly compelled to make art. What better way to explain a sudden urge to make art than to attribute it to the Divine command? Within a Christian community, a frivolous endeavor, one not associated with the working class, can be condoned only if explained within the context of fundamental religious belief, that is, that the images represent another kind of reality and one that is essentially spiritual.”

Untitled (Scalloped Forms), 1944. Crayon, ink, and graphite on paper, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, T. Marshall Hahn Collection © Family of Minnie Evans

One thing that distinguishes Evans from other visionary artists, who as Patton suggests may have leaned especially heavily on their visionary experiences as socially appropriate justifications for their artistic impulses, is that she lived most of her adult life within a community – the estate of Pembroke and Sarah Jones – that did value art very highly. The fact that she was employed in domestic service of the Joneses, however, actually heightened the tension around how to explain where her art came from – could she ever safely admit to any inspiration she might have derived from working in their art-filled home or openly call herself an artist when the social codes of the Jim Crow, especially in the wake of the Wilmington Massacre, forbade that kind of freedom?

When she married Julius Evans in 1908, he was already working for Pembroke and Sarah Jones who had amassed a one-hundred-fifty-acre estate in turn-of-the-century Wilmington. Evans was 16 at the time, and would give birth to three sons over the next decade, raising them in a five-room tenant house that was only about three hundred yards away from the Lodge, one of several extravagant homes the Joneses kept on the property. Once her youngest son, George, turned three, Evans worked in the household full time, with her sons also taking on service roles there as children. The various residences she would look after were filled with works of fine and decorative art, which might have become even more world class once, after Pembroke’s death in 1919, Sarah married Henry Walters, a key player in the Gilded Age practice of building major art collections that would eventually become the cornerstones of major American museums (in Walters’s case, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore). The Pembroke-Sarah-Henry love triangle is one of the many rabbit holes that I started to tumble down in my research for this show, and which I will once again resist here. But suffice it to say that Evans, and the roughly thirty Black domestic staff that served the estate over the years, knew things which required the utmost discretion.

The piercing eyes and sealed lips that appear in the central faces of so many of Evans’ mandalas took on new meaning for me as I learned more about the world of Gilded Age wealth and revelry in which she found herself.

While envisioning the many beautiful tokens of conspicuous consumption that Evans experienced on the Jones estate, it is also important to remember that she had access to other spaces of beauty throughout her life: among them, the home of her grandmother, the many natural spaces she explored living in a river basin region cross-hatched by bodies of water feeding a vibrant ecosystem, and her church — a particularly important force in her life, as she was a leader within her congregation at St. Matthew African Methodist Episcopal Church. Depictions of Jesus that she made in the 1960s, for instance, have more in common with mass-produced images, including an illustrated Seventh Day Adventist text she was known to have favored, than Old Master religious scenes she might have seen at the Joneses. Works with allover patterns like Untitled (Abstract Checkerboard Design), 1943 and Untitled (Paisley Design), 1950s could reflect, as others have suggested, the extravagant rugs, coverlets, and wallpapers that Evans swept, laid, and dusted at work, but they also read like patterned swathes of fabric that she likely saw her grandmother Mary — an esteemed seamstress — plow through by the bolt. The scalloped semicircles that lace the edges of so many of her mandalas and their frequent pendants featuring coastal horizons, meanwhile, may correspond to memories of rising early to gather shellfish with her mother Ella in Wrightsville Beach, in the years they worked as “sounders” before their marriages.

Untitled (Four Figures Collage), 1961, 1967. Collage, oil paint, crayon, pencil on canvases, Collection of John Jerit

Evans’ access to other aesthetic realms notwithstanding, the exceptionalism of the grandeur she witnessed at the Jones estate, which included the extravagantly landscaped grounds that became known as Airlie Gardens, cannot be overstated. In an early 1930 account of the Gardens, writer Cora Harris declares their beauty “incomparable” and muses about the poetry that Homer might have written had he been to Airlie, where Kaiser Wilhelm I’s former gardener, had been hired to create “Earth’s Paradise in all its glory.” In 1912, Sarah’s daughter, Sadie, had married John Russell Pope, who designed various buildings at Airlie including the Temple of Love, a miniature version of the domed and colonnaded structures he would create for the National Gallery of Art and Jefferson Memorial. The Joneses were known for their generosity, hosting the likes of the Astors, the Vanderbilts, and the Roosevelts at their various homes in Newport, Rhode Island, New York City, and at Airlie, where the old-growth trees provided a unique opportunity for formal but Southern-style dinners (they had a Black chef famous for his biscuits and oyster roasts) often held outdoors underneath the trees’ generous canopies. Although hagiographic texts on the Joneses canonize them as generous employers, there are other accounts of abuse demonstrating that they depended on upholding the patriarchal systems of slavery. They do not appear to have been architects of the Wilmington Massacre themselves, but the 1890s marked a period of critical growth for their land acquisition, and they benefited from a deal struck by the coup government which pretty clearly establishes whose side they were on. Starr asked Evans multiple times about the Joneses and the possible influence of the artwork she might have seen in their homes, but Evans would not take this line of questioning. The most she ever said were things like, “You just couldn’t get through to them.”

For Evans, the question of what was appropriate to share must have weighed particularly heavily, and we may never know if there were objects — perhaps even a mandala or two — that seeded some of the cross-cultural similes that feel detectable in her work.

Untitled (Three Large Figures, Night Sky and Stars Collage), 1967. Oil paint, crayon, collage. The John and Susan Horseman Collection, Courtesy of the Horseman Foundation. Photo by Lisa Mitchell

One truth is that Evans’ practice blossomed once she was no longer employed by the Joneses. Five years after Sarah died, the estate was sold, with Airlie Gardens opening to the public and Evans starting a new job collecting admissions at the gate. For more than twenty years, seven days a week, rain or shine, she sat at the entry, first unsheltered and later in a small gatehouse. Outside of the popular Azalea Festival that showcased the Gardens’ seven hundred thousand specimens, visitors trickled in, allowing Evans time to read, pray, and make drawings. She cherished walks through the Gardens and reflected lovingly on this period in her life: “Sometimes I want to get off in the garden to talk with God. . . I spent many happy years there.” The Gardens supercharged her art with its dizzying number of plants (and their pollinators). Begonias and primrose, butterfly wings, garden statuary strewn with jasmine vines, moss, and English ivy, and urns bursting with potted arrangements appear throughout her drawings. Evans did not catalog specimens in the scientific way of a naturalist. Instead, she translated the ordered chaos of Airlie into compositions that overflow with color and organically flowing rhythms.

Photo of Minnie Evans, 1969. Photo by Jack Dermid. Courtesy of the Cape Fear Museum of History and Science, Wilmington, North Carolina

In one the earliest portraits that Nina Howell Starr took of Evans in 1962, she wears a dress whose floral pattern matches the botanical richness of her garden setting. A later portrait shows her extending a drawing from the window of the gatehouse — a posed image, to be sure, but one that captures how Evans would share her artwork with garden visitors and claim the gatehouse as her first gallery. In a third portrait, also from this period, Starr captures Evans’s face cast in an array of light. This portrait would be used for a short but important profile on Evans that ran in the iconic feminist magazine, Ms., in 1974. The profile also included a short write-up with several quotes from Evans, among them her insistence that her drawings were “just as strange to me as they are to anybody else,” and a spread reproducing four of her artworks. One of the most remarkable circumstances of this appearance in Ms. is that on the very next page, the reader encounters In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens, one of Alice Walker’s most iconic essays. In this groundbreaking and enduring tribute to the resilience of Black women’s creativity, Walker never mentions Evans but describes women like her with amazing precision: “They dreamed dreams that no one knew — not even themselves, in any coherent fashion — and saw visions no one could understand,” Walker writes. Throughout the piece she asks a series of painful and poignant questions, including one that again speaks directly to Evans: “Was she required to bake biscuits for a lazy backwater tramp, when she cried out in her soul to paint watercolors of sunsets, or the rain falling on the green and peaceful pasture lands?" Walker wrote this essay in tribute to the generations of women whose creative spirits were crushed or unrecorded, and who therefore could not be named or acknowledged for what they could have or did achieve. She also paid homage to specific women whose accomplishments are known, including the poet Phyllis Wheatley and her own mother, a prolific gardener who was named — you can’t make this up — Minnie. Evans may not have been directly cited in Walker’s essay, but as the editors of Ms. surely understood, she embodied the archetype of the magnificent creatives about whom Walker wrote. By making and sharing such an extraordinary body of work, Evans determined that her world would not be lost. We are so lucky to know her name and her vast artistic achievement, which we invite you to experience in Atlanta, New York, and through the pages of our book, beginning in November.

The Lost World: The Art of Minnie Evans will be on display at The High Museum of Art from November 14, 2025 – April 19, 2026. The exhibition will travel to the Whitney Museum of American Art after the fall 2025 debut in Atlanta.

###