INFINITE MONUMENTS OF COASTAL GEORGIA

A postlapsarian picaresque in which two friends,

Pete and Ryan, light out for the Peach State’s swampy southern

border and a squinting date with history

by Ryan Madson and Peter Relic

“Let’s listen to that Stones song again,” says Pete, reaching for the rental car’s pushbutton stereo. “The one about the demented monkey.”

Ryan raises his hand in the universal sign for hell naw.

“Once was plenty,” he grumbles. “Don’t you remember what happens in ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’?”

While Pete may be preoccupied with those simian Rolling Stones, Ryan has another monkey in mind: the one who appears in Savannah-native Flannery O’Connor’s short story from 1953. Partly about a road trip gone horribly wrong, the story features a gray monkey chained to a chinaberry tree, symbolizing the devil, or perhaps the sulfurous devolution of all humankind. This sets the tone for miles of unchained conversation ahead.

Greetings from Georgia where the air is wet n’ wooly and there’s nothing for it but to set the controls for the heart of the swamp. Thirty minutes earlier we had departed from Savannah. It’s the last weekend in July, and we’re rollin’ and tumblin’ down Highway 17. We came down here with an idea: to locate and write about unintentional local monuments. There’s the forty-foot-tall red boot above Callie Kay’s Workwear in Waycross; the fat plaster cow in front of Keller’s Flea Market in Georgetown; the grinning plastic mascot, overdue for a power-washing, outside the Piggly Wiggly in Eulonia.

Piggly Wiggly, Eulonia. Photo by Susan Laney

But that’s all a pile of roadside kitsch. We’re after something else, the thing that was never intended as an attraction, but somehow still feels monumental. Our antennae are up for emblems of durability and significance. We soon become attuned to quieter monuments to precarity, too.

The Highway 17 corridor showcases Coastal Georgia’s scenic beauty, a natural wonder often taken for granted. The route skirts marshlands with postcard-perfect vistas, passing through hazy semi-tropical forests before opening yet again to another estuarine viewshed. Small towns, hamlets, and public parks offer stepping stones along the way.

The area is defined by its uneven development. Pockets of rural poverty and social disinvestment exist alongside vinyl-sided suburbs and, nestled further back in the trees and at the marsh’s edge, gaudy vacation homes.

Historically, Highway 17 was called the Savannah–Charleston Trail, or King’s Highway, which traversed the Low Country as it connected the two cities and their agricultural hinterlands. A ferry was the only way to cross the Savannah River until 1922, when a bridge was constructed near Port Wentworth. The Old Talmadge Bridge opened in 1954 and directly conveyed Highway 17 from Carolina into downtown Savannah.

This “bridge to prosperity” shortened the drive and brought regional through-traffic, including southbound tourists on their way to Florida, into the Savannah metro area and the Georgia coast. This was during the golden age of the American road trip, the pre-interstate highway era of motels and diners and roadside attractions.

As ships entering the Savannah River ports grew larger and taller, the old cantilever truss bridge became obsolete and was replaced by the cable-stayed bridge that exists today. Piers from the old bridge remain on either side of the river’s main channel; the hubris of the modern engineers overshadows the old ways.

These silent, less-than-heroic artifacts within the shadow of the new bridge are the first unintentional monuments that we take note of today. We cross from Yamacraw Village, near the foot of the bridge, to Ogeechee Road and along Laurel Grove Cemetery (actually two cemeteries segregated by race and separated by a freeway entrance).

Within minutes we merge onto Highway 17 as it ramps down from the elevated parkway. We pass a motel that was once called the Manger Towne and Country Motor Lodge. Back when this busy stretch of highway was a two-lane blacktop, the Motor Lodge featured a swimming pool out front, and served as an overnight stop for a youthful, pre-imperial Rolling Stones on their 1965 tour of the East Coast. A relic of the motopia of yesteryear.

Soon we catch our first glimpse of tidewater and expanses of tawny cord grass. Highway 17 crosses under Interstate 95 and the corridor becomes rural. Passing through a low-lying area near Riceboro, Ryan points out that all this will be underwater one day: “A vast river delta, from the Savannah to the St. Mary’s.”

Manger Towne & Country Motor Lodge, Savannah, GA

The route veers east again and affords views of the marsh and the barrier islands beyond. We slow down through Eulonia, the gateway to Sapelo Island, and come to a stop in Darien beneath the canopy of an ancient live oak tree on Fort King George Drive. A fleet of shrimp trawlers recalls the once-bustling port of the Georgia colony.

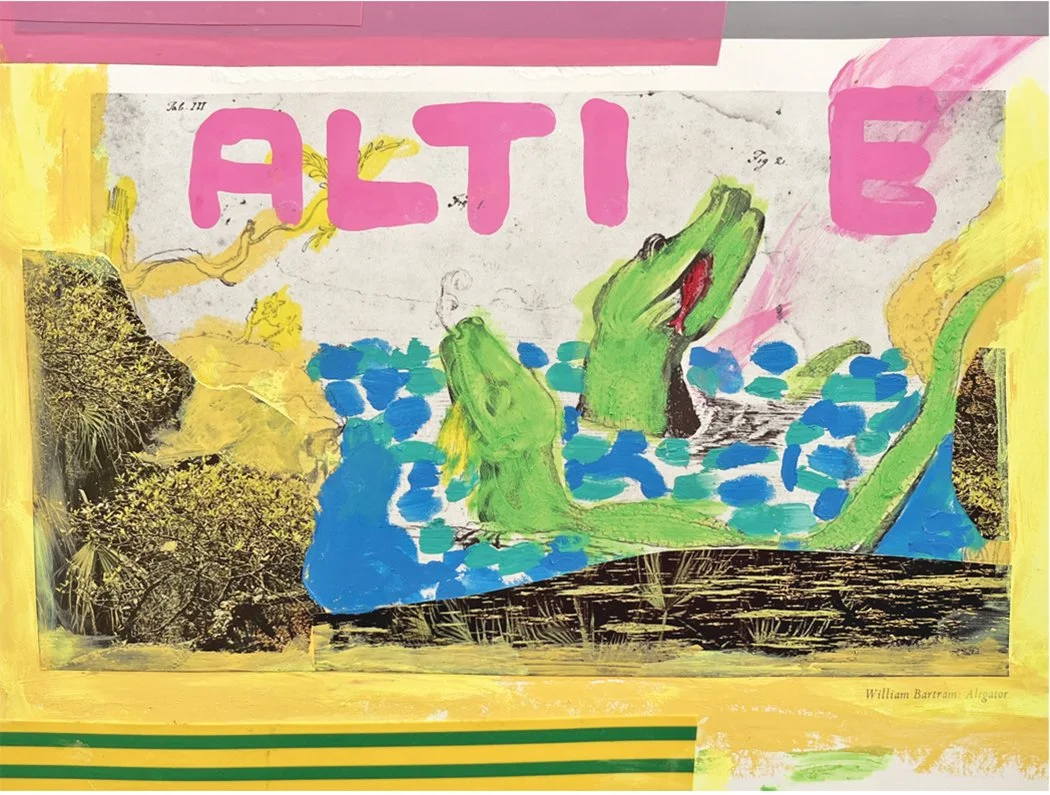

Have you seen Altie? by Ryan Madson

We buy two iced coffees at a café and stroll along the riverfront. The bluff seems to be held in place by patinated ruins of thick tabby concrete, the foundations of a formerly imposing frontage of shipping warehouses. Near the bridge we peer out at the dark waters of the river that forms part of the vast Altamaha.

“Keep an eye out for Altie, the Altamaha-ha monster,” Ryan advises.

“What is that?”

“It’s like the Loch Ness monster of the Altamaha River. The legend goes back to the Muscogee Creeks who used to live here. Probably sightings of giant alligators or sturgeon.”

Pete considers this. “But it’s more fun to believe.”

A raft of marsh wrack flows gently past. A chevron of migratory birds scopes out fresh habitat in the wetland utopia of the Altamaha Wildlife Management Area. Instead of an Altie sighting, we are rewarded with a subtle sense of creatures living in harmony with the rhythms of the coast and its fragile ecosystems.

“You want to see the Marsh Ruins?” asks Ryan when we get back to the car. “We’re right near there.”

We continue down to Brunswick and flip a blip on Glynn Avenue. We find a parking spot at the south end of Overlook Park along Brunswick’s sparsely developed marsh side. It was here in 1981 that artist Beverly Buchanan lodged mounds of tabby concrete into the mud between the highway and tidal river.

There’s no sign to indicate the Marsh Ruins are here. Perhaps the point of Buchanan’s environmental sculpture is to question notions of prominence, of durability and disposability, maybe even the whole “believe in it and salute it” mentality of the country. As art critic Amelia Groom wrote, the Ruins “enact a curious and delicate tension between destruction and endurance.” They are gradually being reclaimed by the tides.

We walk to the trail’s end, into the muck. Sagging in the sea grass beside discarded cans of Keystone are Buchanan’s hand-hewn mounds made of oyster shells and sand. The artist’s crumbling work may appear intentionally pedestrian, but standing here feels like being let in on an enigmatic secret. There’s a monumental thrill to that.

Instead of heading back to the car, we walk out onto the nearby pier. Its slats are smeared with shorebird shit and fishing bait. A place designed to cast a line for black drum and spotted seatrout. Nailed to the warped wood railing is a faded marking stick for measuring the day’s catch, reading “Do Your Fish Measure Up?” Gazing back towards Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins suggests another question: Can any monument compare?

Photo by Ryan Madson

Monument, from the Latin monumentalis, “something that reminds.” The Cambridge definition: “an object, especially large and made of stone, built to remember and show respect for a person or group of people.” The etymology includes Old Church Slavonic “mineti” (“to believe”) and Greek “memona” (“I yearn”), but also related to the Greek “mania”: madness.

No wonder the idea of a “monument” feels fraught. We drive on, and near the unincorporated hamlet of White Oak, a sign recruiting for Sons of the Confederate Cause points backwards. Whereas the words “LUMPIA – ICE BAGS – FISH DIP,” painted in red lettering on the side of M&A Seafood, seem of more useful and immediate consequence.

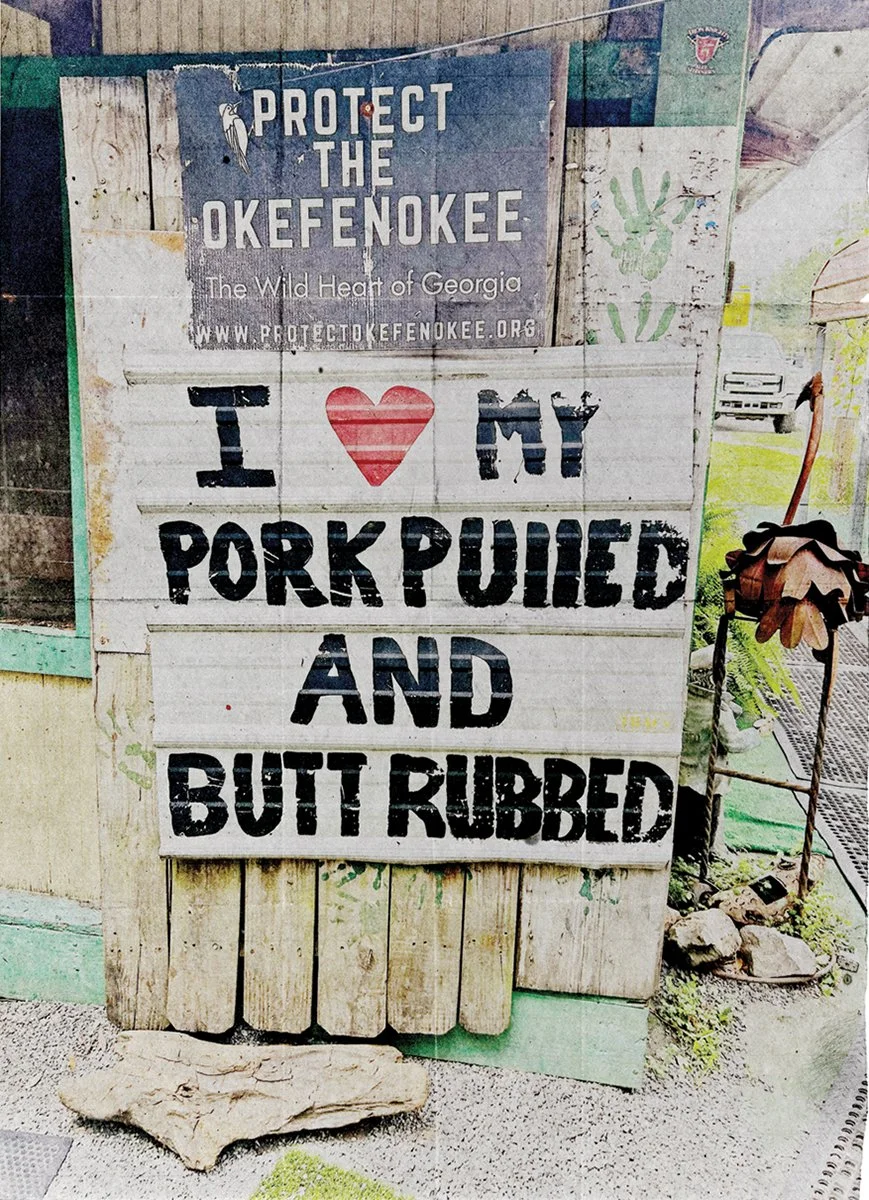

We aim for the lunchtime rib plate at Captain Stan’s Smokehouse. In the unpaved parking lot in Woodbine, a sign announces “I Like My Pork Pulled & My Butt Rubbed” — and ain’t that a monument to a rootin’ tootin’ good time?

“You get two sides with that,” says our teenaged server Hannah, after we plant our butts on benches in Captain Stan’s canopied garden, where a dozen picnic tables are arrayed around a faux-wood linoleum dance floor. Soon, monumental piles of potato salad and tangy collards arrive with the scorched red ribs.

“Does this place get hopping at night?” Ryan asks. In the corner, a giant silver basin sports a spigot with instructions: Free Georgia Holy Water – Serve Yourself.

Hannah bares her braces and shrugs. “Pretty much. We have big groups of bikers come through. It’s fun.”

After lunch we backtrack a few blocks to make the turn to nearby Folkston. Ryan muses with enthusiasm about the detour:

“The Swamp Thing. DC Comics. The original swamp-keeper, wasn’t he from the Okefenokee?”

“The Bayou, I think,” responds Pete.

“Well, Swamp Thing needs kin up here. The locals could use a benevolent, post-human vegetable person to protect them from that mining operation, the one that plans to dig up the edge of the Okefenokee.”

Later, research reveals that a conservation purchase was made to protect 8,000 acres near the southeastern boundary of the Okefenokee, the largest blackwater swamp in North America. The area had been threatened by a permit for deep earth mineral mining. The swamp is safe – for now.

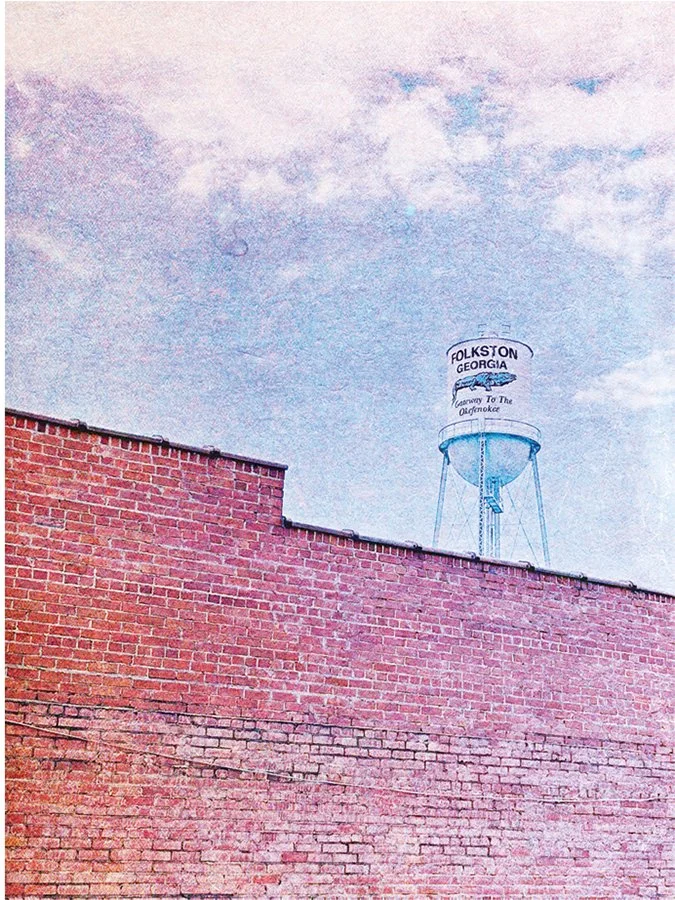

By the time we reach Folkston, proud hometown of NFL Pro Bowl cornerback Champ Bailey, (swamp) things are looking up. Literally. “Gateway to the Okefenokee” reads the legend painted on the town’s imposing water tower, an alligator mural wrapping around its elevated tank like a rugged tattoo on a bulging white belly.

Near the corner of Oakwood and 2nd Street we spot a bait and vape shop called FLY ASH. We must be headed in the right direction, into the place that Pogo calls home. As that comic strip’s creator Walt Kelly once wrote: “The personal hummock in our common swamp is frail.”

The long, narrow road into the swamp is lined with tall, narrow pines. The trees are being sprayed by a short pudgy man in a cowboy hat seated in a work chariot, and as our car rolls past, whatever he’s dousing the trees with from his cannon-hose seems to sizzle with venom. “You think that stuff kills him, the weevils, or those poor loblolly pines? All of the above?” Ryan asks.

In a famous Pogo strip commemorating the first Earth Day, the philosophical opossum muses: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

Photo by Peter Relic

We feed a machine the five-dollar entrance fee and enter a parking lot in the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, bereft of cars and souls. Why would anyone be here on a summer day this hot? Then we see it. Glinting in the asphalt’s furthest corner is a silver scimitar, hovering on a flatbed. We park next to it. It’s the University of Georgia Alligator Research Boat, abandoned to the elements. A minor monument to the swamp itself.

We could use that boat now. Instead, we venture into the Okefenokee on foot. Overhead, fluffy airships scud through the blue beyond, and humidity achieves singularity. Nature is a concept. We sweat like burst pipes inside a wall.

A few hundred yards down the Cane Pole trail, we glance over at a fat knot of wood bobbing in the black water. Then it nods to us before showing its ridged back just above the surface. Not a log, a gator, an eight or nine-foot zipper peeling back the abyss. Air bubbles and muck burble to the surface. Chain pickerel splash out of its way, gulping bugs, a late lunch and last supper.

When you’re in it, you don’t really have a sense of the expanse of the nearly 630 square miles the Native Americans called “The Land of the Trembling Earth.” On a map, the shape of the Okefenokee — the outline of the swamp — resembles the silhouette of a haunted man with a drippy nose. Perhaps, allowing for an imaginative leap, the map-man in profile is the fugitive Tom Keefer (played by Walter Brennan), on the run from a murder rap, in Jean Renoir’s 1941 film Swamp Water, made not on a Hollywood backlot, but in the Okefenokee itself.

To get from Folkston (approximately Tom Keefer’s ear) to Waycross (the top of his head) would be a torturous journey through the swamp, not to say impossible.

“You can walk it solo next time,” says Ryan, with a gentle pat on the back.

In one particularly affecting passage of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, journalist Stanley Booth, a Waycross native, reflects on his Georgia boyhood. Ryan, in the passenger seat, finds a passage about the swamp and begins reading aloud:

“One afternoon at my grandfather’s house near the Okefenokee Swamp, where I heard the sounds in the night, I was sitting on the front porch, listening to a Ray Charles record that I had played on my grandfather’s Sears and Roebuck record player. It was summer and I was visiting my grandparents. Their house was set in the shade under two sycamores in the little turpentine camp where the roads from Waycross and Homerville headed….”

We’re on that road now, or as close as a needle gets to a groove. Ryan continues reading:

“A black girl from the quarters heard and came and sat on the steps of the screened porch. We talked a bit about Ray Charles and Memphis before my grandfather came and chased her away.”

Photo by Peter Relic

We park at the stanchion behind Plant Café in downtown Waycross. The sky is turning pink, less like strawberry frosting and more like old foam insulation. We wonder about that inquisitive little girl, the one who Stanley’s grandfather had chased off the porch, and speculate that she’d grown up to be Beverly Buchanan (an impossibility, as the late artist had grown up in the Carolinas). Fanciful stuff — trying to make bits of history fit like scattered puzzle pieces, hoping for a bigger picture.

Not many people are about in Waycross. On the corner of Folks Street and Carswell Avenue is a castellated home with a sumptuous, screened-in porch. Once it was grand. Now it lists to one side like a drunk. The blue tarp strung across its roof flaps indecently, revealing the gaping hole beneath.

We keep walking, past a vacant lot, over a low berm, and stop at some scrawny-treed woods that bleed into the Okefenokee. It’s easy for the imagination to picture an old turpentine camp coming into view. But here, there is no monument at all apart from the timeless, yawning swamp.

We finish our detour along tertiary roads, back to Highway 17 for the final stretch. In honor of Gram Parsons, another Waycross native, we tune out to the cosmic country sounds of Sweetheart of the Rodeo by The Byrds.

It’s late afternoon. We’ve finally made it to St. Mary’s. The sky has become a ruddy puce. With compulsory ice cream cones in hand, we loiter near the Cumberland Island ferry on the edge of the river that forms a border between Georgia and Florida. Long ago, when Guale people inhabited this part of the coast, pirates and European merchants sent skiffs up the river to supply their ships with fresh potable water.

In St. Mary’s, the culminating southern point of our trip, the sleepy pace of life is overwhelmed by panoramic beauty and the immense, inescapable presence of the marshes and tidal rhythms. Before leaving the waterfront Ryan jots down some notes, intended as an introduction to this essay:

“Highway 17 and the coastal empire it traverses are destiny. The region hosts authentic, deeply rooted, and oft-overlooked ways of life, yet it also prefigures our coastal futures shaped by global heating and economic decline. Perhaps this is no place for permanent monuments, only traces of ourselves, mysterious ancient patterns, and complex ecologies that we barely apprehend….”

That evening we return to Savannah by express: blasting up I-95, the windows closed, all but oblivious to the nearby presence of the slow route we had just taken in the opposite direction.

###