“The Rose Garden,” 2023. Velcro, oil on panel and canvas, 48 x 72 x 2.75 inches. Photo by Mike Jensen, Courtesy of UTA Artist Space

Earlier this year, Joshua Alexander of IMPACT Magazine interviewed Baltimore-based artist, James Williams II and discussed profound topics that influence Williams' art. Using painting, video, and collage, Williams examines what he calls the Black Construct, highlighting the tension between objecthood and personhood.

As a new father, Williams began to take inspiration from the creativity and play inherent in that role - as well as the deceptively simple questions posed by his two young daughters. Williams innovatively employs commonplace materials like Velcro, chalk and yarn to craft insightful commentaries on the Black experience - through work that is deeply personal and rooted in his own lived experiences.

Joshua Alexander: In your artist statement, you talk about how the idea of the Black person is anthropomorphized and fluid – I feel like it ties into this idea that we previously discussed: there are shells or layers of perception on top of us, but the organic truth that we all share lies underneath. Can you speak a bit more on that?

James Williams II: When I talk about Blackness, I usually put it into two different categories. For me, what I'm talking about is more of a Black Construct and not the Black person. I think we talk about the Black person a lot, but we belittle the person – “black” usually becomes the preface before we begin to acknowledge the person. The person is really what the context is, and it is something that usually does not get the same look as the “black” that comes before it, right?

So when I think of a person, I think about the mind, the soul, the body, all that makes us who we are, and that gets belittled because “black” is before it. Or white, or asian, or whatever. All those things we use as monoliths to put everybody into boxes. So I have to call it for what it is: it’s a construct, something created when we grew up as young kids, young men, as young boys and girls, that we even acknowledge the difference of our skin as something that relates to social and economic contexts.

So for me, the Black Construct has been a conversation present in a lot of things I've read, but I've always understood it through a more academic sense. It wasn’t until my daughter began to ask difficult questions at a young age, that made me explore it further. I don't hide much from my daughter – if you ask the question, I answer it. I do try to convey, breakdown, and simplify, but I don't stay away from questions, and I think my family did an okay job of that. I think that when my daughter started asking questions about race, I met her where she was at. The simplicity of her questions required complex answers. Then, I realized that this won't make sense at her age – I can't simplify something that was never meant to be simplified, there are complexities to the Black Construct.

James Williams II in his studio, 2023. Photo courtesy of the artist

When I refer to anthropomorphism, I'm really thinking about something that she can acknowledge. Mickey Mouse is not real. It is fake. There is no actual mouse named Mickey, and we have personified who Mickey is. We have given it characteristics, we have told it what it is. Now we even have people who put on the whole outfit to pretend that they are Mickey Mouse. We have made it real. And just like Mickey Mouse, we do the same thing to this Black Construct.

We need a villain. We need the Antichrist. We need the person that steals – the thief, the greedy person – we need someone that makes us, the other, look better. And so they created a construct, and they looked around far and wide to find who that could be. And I don't think it was something that was strategically planned out – but it was inevitable. And the way that they removed our personhood when we were brought to this country – what they gave us in return was a lacking; something that they can mold into what they think is right. The first thing was, they had to take the person and make us an object so that we would not revolt. I think about Bacon’s Rebellion, which was a good example of white slaves and Black slaves fighting together against those in power.

Anthropomorphism is the way I explain to my daughter the chronological order and the way that I perceive the Black Construct’s fluidity. It started with us as objects. Then we can talk about the Civil Rights Act, in ‘65, how that was to regain personhood. And you could argue that maybe we didn't fully regain it.

But I do think capitalism, in itself, has awarded us these opportunities to be more in the limelight, to be more able to use our voices. I also realize, when you have people like Colin Kaepernick, and on the opposite end, Jay-Z, in these crucial moments of conversations about race and police brutality – what it looks like when we become an object and what it looks like when we return to personhood. I think that is what anthropomorphism in the Black Construct can look like. And it’s the other that decides what they want to take in, to create the monolith that is the Black Construct. But when you have Colin Kaepernick kneeling down, he became a person, and they didn't like it, because he was supposed to be an object. That's why you have news reporters saying to Lebron “shut up and dribble”, because in their mind we’re an object for their entertainment – “We pay you to entertain us, not make us feel bad.”

“Soft Embrace,” 2023. Oil on panel and canvas, Velcro, yarn, 30 x 24 x 2.75 inches. Photo by Mike Jensen, Courtesy of UTA Artist Space

There's so much I have to think about when I make the work. I'm thinking about my daughter. I'm thinking about the muckiness of it. And her simple questions - like, “why do people call us black when we’re brown?” And I'm like, you know, you're right. There's wide shades of black and brown individuals who are put into this monolith as this kind of one size fits all. I have people who, you know, came out of Jamaica in the last decade, and when someone asked who they are, they’re like “I'm Jamaican.” And then I'll be seeing them again, and they’re like “yeah, I’m Black.” - because they gave up. They gave up because race plays such a big part here and not so much ethnicity. But the Black Construct does not make room for ethnicity, and that's historical, but we do have an opportunity to look at it differently. So that's where the paintings come in play. I have to be careful when I make the paintings – and there's so many paintings I've made that I have to destroy – because I'm not interested in the social justice conversation in the way that I think other artists might be. For me, the best conversations are the most intimate ones.

If I can't have an intimate conversation with everybody, then there's no point in me having this big conversation that I know I can't fully control.

Art is an opportunity for everyone to take in their own experiences. I want to be able to make sure there's clarity, but also wanna make sure that there's some broadness to the work as well. I try to make it very clear that a lot of the work is personal. I don't talk about things I haven't experienced, I don't talk about things that I don't go through or think about – and these are conversations I have with my daughter. So a lot of times, my daughter, my oldest, can look at a painting and say, “oh, is that what you're talking about?” There's some things that she doesn't know yet, cause there's some things that are just deep trauma. So I just haven't really had an opportunity to explain it to her yet.

But to clarify, the Black Construct, and anthropomorphism is really the flipping. The flipping is going from a person to a thing, back to a person. And we have so many examples of that. I don't think that's how we're supposed to view things, but I think we do it because it's easier. It's easier to assume that the person across the street who has a Trump sticker is the embodiment of everything bad about Trump, rather than understanding, “Why did they get there? How did they get there?” Empathy is something that we're losing a little bit. I think if I can try to have empathy for others, even if it hurts, then people are gonna have empathy for me.

I'm looking for conversations. I'm looking for moments that I can use and be like, “Hey, you know, upstate New York was not easy for me as a Black boy or Black man – to live in a predominantly white area.” I'm just kind of being vulnerable in that. I would rather talk about the things that actually happen to me. So I'll be painting what I'm doing, or something that really has resonated with me or something that really has had an effect on me, personally.

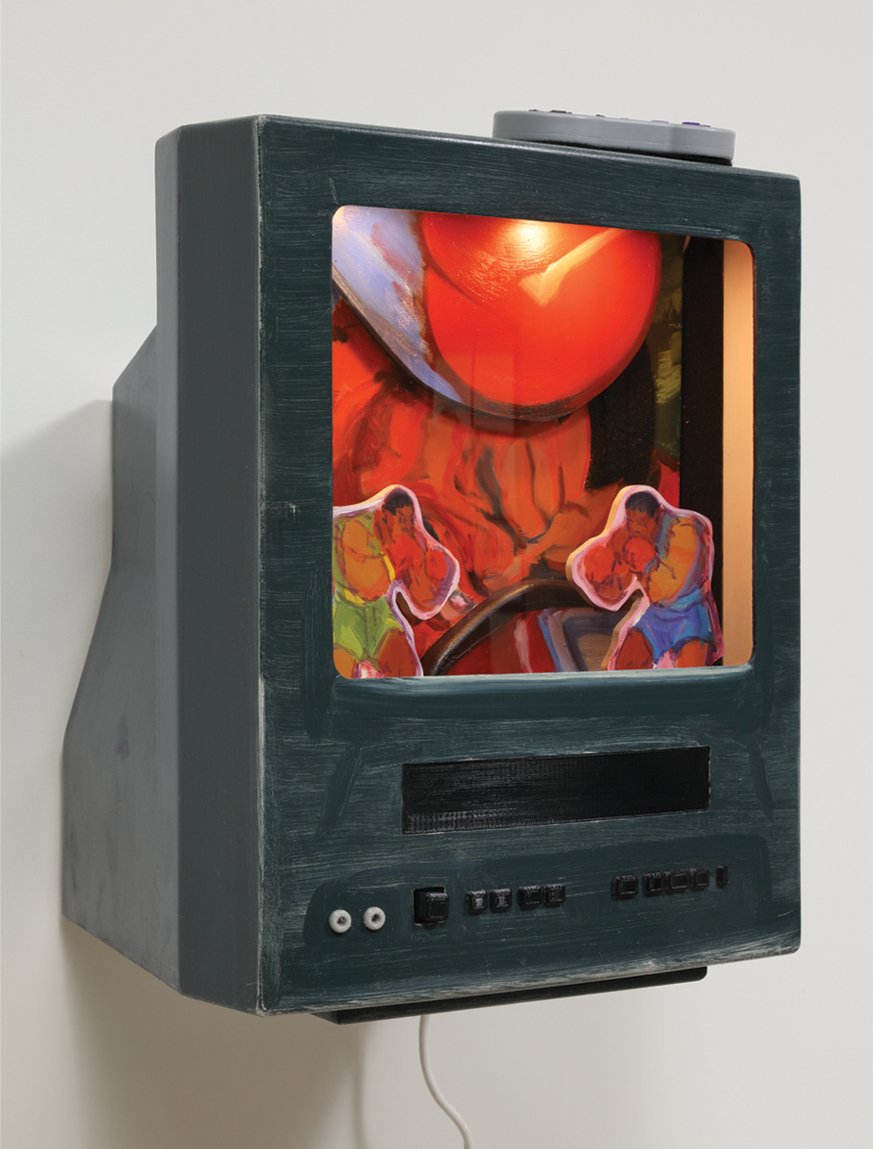

“Trippin,” 2022. Velcro, polylactic acid, lightbulb, 41 x 27.25 inches. Photo by Mike Jensen, Courtesy of UTA Artist Space

JA: I've been talking to a few artists down here lately, about a space for contemporary Black art – contemporary as in speaking to current circumstances and personal affects. Oftentimes I find there's a sort of inclination or an affinity for things that are more historical rather than personal, and when I looked at your paintings I instantly felt that personal connection. It was the Velcro for me. That was such a prominent part of my childhood, and such an important material in my household. To see your color choices and those layers is like – Fresh Prince – I got it! The way that you tied it together through all of your work, with the paintings in particular. Was it obvious that Velcro was gonna be your go–to? Was it the feeling of it, the meaning, the poetics? How did you settle on that?

JW: There was a moment when my daughter was a baby, and I wasn't as active in my studio as I wanted to be. I think every parent kind of goes through this: you begin to be so preoccupied with encouraging, cultivating and lifting up your child that you’ve just seen come into this world, the things that you were doing beforehand become less prevalent in your life. If you're a creative person, that could be very hard because that might be your output, that might be the thing that you do to find connections. Maybe the connections now are limited to baby talk and seeing your child grow. I think that was, at first, very shocking for me. But then I began to realize that no matter what I do in the studio, I could never create anything better than these two kids. And when I would spend time with them I realized I was being creative.

And instead of what I was used to doing – these big, large paintings – I began coloring in coloring books, and really having fun with that; playing around with these Velcro toys, and just got lost in their world, got lost in the materials that they were using. And then when I finally did have some time to go into the studio, I’d be totally confused. “What the hell am I doing?” I would have half finished paintings, and I would look at them and say, “I don't even know how to finish this.” So I would start again, and I would try to go bigger, and bigger wasn't working. Then I would try to go smaller, and smaller was like, “Okay, this is fine, but I'm not connecting with it.” So, as I was having these conversations with my daughter and as I was reading a lot of books regarding Black Constructs and the ideas behind identity, I began to give up on what my expectations were in the studio.

“Force Majeure,” 2023. Velcro, oil on panel, led lights, resin, polylactic acid, and plexiglass, 17 x 14 x 14 inches. Photo by Mike Jensen, Courtesy of UTA Artist Space

There's a lot that happened all at once. Nothing really came in a way that I can spell it out, but Velcro, at one point became something that had both symbolism and also function. I began to realize I could take these collages that I didn't know what I was gonna do with and see what happens. Rather than make the illusion of a collage, I'm gonna actually make a collage and start thinking about material. Velcro became it. But it wasn't enough. I tried that. It was like, Okay, this is fine. But I couldn't really understand why it had to be Velcro – it made sense to me, but it had to be deeper. For me everything has to have layers. All my paintings have about 2 or 3 layers – there's some personal layers, there's layers that you can really get right off the bat, and then there's some in-betweens – so I wanted the Velcro to be something more than just the thing that holds the thing up. I began to think about the anthropomorphism of the construct, and the idea that if this black Velcro can operate in a way to help me tell this narrative of what it feels like to be an object to some, and a person to another, then this material is gonna work.

And so I try different things. And what really kind of happened was just a late night making these little wood panels. I put Velcro on the back of it, and looked at it a little bit, and then I put little eyes on it, I said, “Oh, shoot! Now, this is the person, I've made a person by just putting two eyes on it,” and then, as I took the pieces off, it went back to being an object. I'm like, “this is it, this is what I need! This is how I describe this feeling to others who will never be able to understand what it feels like to be a Black man.”

The moment I take these eyes off, they become objects, it becomes Velcro again, but the moment I put eyes on it, then it becomes this person, and now it’s Mickey Mouse. Now I can give it a whole personality. So you'll see in my paintings, I never put a whole body in there, because I wanna make sure it stays flexible, that it can always be the object that people want it to be. And I can force it to have the personhood by adding these other objects onto it. My friends kind of laugh at it because I go in so many different directions. You'll see me researching all these different materials or researching all these different ideas, and then it all comes together naturally, organically. I don't plan on it. I don't sit back and say I need to make these two puzzle pieces fit. I usually just sit on things, the Velcro was sat on for years until my daughter started talking about race. And then I'm like, “Oh, that's what I wanna use.”

JA: When you look at the paintings, your art is literally a reflection of life - a literal interpretation of how you see life.

JW: We're not as simple as we make ourselves. We are so complicated, we're so complex. And I think, to understand each other we put ourselves in boxes. And sometimes, as Black Men, we are okay with being a box, because then everything's simple - but we lose something. Now I'm 41, I'm like, man, I just wanna build some deep relationships.

“Red, White and Blue,” 2023. Velcro, oil on panel and canvas, yarn, 60 x 72 x 3.25 inches. Photos by Mike Jensen, Courtesy of UTA Artist Space

But I think, you know, what pushes me to make work. What pushes me to connect with others is just my human nature. Money is great, it's cool, but there'll be days where I won’t have money and days when I have too much money, and I don't want that to kind of be a sense of value. For me the enjoyment starts in the studio, and the moment the works leaves the studio the enjoyment is gone. The formalities of going to the openings, they're fun but they're out of my element. Like you said earlier in our conversation about clubs - I don’t go to clubs - sometimes the openings feel like little clubs, and I don't really go to those. That could be a lot of the pandemic talking. I think the pandemic, as it was destroying so many lives, it also awarded all of us the opportunity to kind of reset and see what we really needed. I don't know if we would have gotten there if it wasn't for something global like that. Sadly, it brought out a lot of our bad nature - that kind of shows our ugliness. But it also brought some things closer. My two daughters are super close now because of the pandemic and I would say I would pay money just to make sure that happens. I wanna make sure before I leave, my daughters are always relying on each other, are always connected. My life's goal is to make sure that they're good - as I have been blessed to be where I'm at, that people have made sure I'm good, and made sure that I would rise up from their blessings. I wanna make sure that my kids have the same opportunity in a time where everyone's looking at the bleakness of the the next generation. A generation that can't buy houses, a generation that has to be concerned with climate change, a generation that has to be concerned with having autonomy over their own bodies. They need each other as they go into whatever this world is gonna offer them - especially as Black Women - they're gonna need each other.

###